The most recent and relevant example of how dramatically technology can impact our global future is probably the smartphone. In less than a decade, it has gone from non-existent to entirely irreplaceable. This singular device has revolutionized our everyday way of life in so many ways, yet the public desires even further innovation. In other words, can you imagine switching back to flip phones as our communication technology of choice? While a small minority will desire to return to a more simplified state, the general public will continue to pursue the path of enhanced technological innovation.

Historical context

For roughly a century, the utility industry has executed a steady, predictable business model, following a top-down strategy. Electric utilities, and associated legislative and regulatory bodies, have been in the driver’s seat for quite some time. They are accustomed to driving the direction of the energy grid and knowing how best to deliver energy to customers. However, the utility industry is currently being drawn into a new paradigm. The changing desires of utility customers, and a marketplace that is ready to provide new solutions, is propelling this shift. In other words, for the first time in history, utilities will have to embrace a new type of competition. Competition that seeks to provide utility customers with a multitude of new and evolving solutions that will all reduce a utility’s primary source of revenue.

The customer and the market are now driving innovation. The call for change is originating from the edge of the distribution grid (i.e., the places where people utilize energy), rather than waiting for innovation to develop and work its way down from a centrally controlled utility construct. While the customer has always been a key component of the utility business model focus, up until now customers never had enough clout to tangibly shape or alter the industry’s direction. If you visualize the end nodes of the power grid as the tail of a dog, and the central station generation assets as its head, you could say that the tail is beginning to wag the dog.

Imagine you have been the head for nearly a century, and you can begin to understand why this topic creates feelings of discomfort and disbelief. Just as it is difficult to imagine a dog’s tail leading its body, it is a struggle to envision such a monumental shift occurring in the electric utility industry.

Patterns exist

Although the future of the energy industry is uncertain and no one has access to a magic crystal ball, one thing is clear – the future will be more complex. This added complexity is primarily due to a shift from unidirectional to multidirectional power flow on the grid system. In other words, energy generation is coming from sources other than central station assets, such as large coal, nuclear, or natural gas plants. Distributed energy resources (DERs) will not only originate energy at the edges of the distribution grid, but will also help the general public to reduce and optimize their energy use.

DERs include various forms of distributed generation (DG), but also encompass an assortment of devices, controls, and intelligence that work together to optimize grid system operations.

Up to this point, the utility industry has largely been driven by three key attributes: cost, reliability, and safety. Of these, keeping costs low has been king. Cost effectiveness has primarily been evaluated by how efficiently utilities could recover capital debt from the construction of large central station assets. As long as this was done in a financially prudent manner, and electrical reliability was kept high, the utility industry was generally content to benchmark themselves against other utilities in these areas. Since electric utilities have always had a majority of the control in shaping their future direction, this type of industry focus and benchmarking was actually quite predictable. Said differently, why wouldn’t electric utilities focus on these metrics, given their historic business model construct? However, as a new utility business model begins to emerge, the fundamental building blocks and metrics will also have to adapt. This is a fairly straightforward conclusion to reach, but shifting the paradigm of a well-established industry is anything but simple.

A tale of two futures

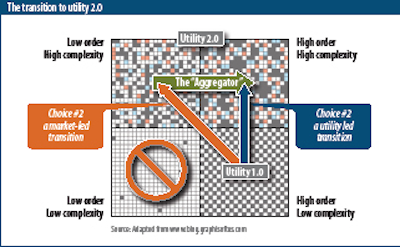

Visualizing the future direction of the utility industry can be effectively accomplished by utilizing a four-quadrant matrix (see p. 48). The matrix deals with two primary variables: complexity and order. Complexity is mapped from the bottom to the top, moving from a state of low to high. Order is mapped from left to right, moving from a state of low to high order (i.e. organization). This quadrant helps to map the future of the electric utility industry from its current state (Utility 1.0) to a future state (Utility 2.0), from a very high-level perspective.

If Utility 1.0 currently resides in the bottom right quadrant, the first thing we notice is that to transition to Utility 2.0 we must move in an upward direction. In other words, moving to a state of “low order, low complexity” (bottom left quadrant) is not a logically consistent end point. Therefore, this leaves us with two potential futures, both of which involve a growing degree of complexity. The first choice, a utility-led transition, moves us directly towards a state of higher order and organization.

If the utilities lead this transition, there will naturally be more alignment, because there is only one or a few primary governing bodies driving the overall holistic direction. The notable downsides of this choice come in terms of increased bureaucracy and reduced speed. The electric utility industry is not a fast-moving sector, and it intentionally incorporates several layers of approval processes. This type of construct was effective in a “Utility 1.0 world,” but is now seen as an impediment to change by those outside of the electric utility industry.

The second choice is a market-led transition. In this future, various DER solutions providers drive the direction. While speed of movement is accelerated, an increase in chaos (movement towards lower order) is also a natural result. This is primarily due to an assortment of market players with varying objectives and corporate goals. Simply put, the more people and businesses you have aggressively going after a similar market share, the greater the potential for holistic misalignment and market divisions. If we are shaped by a market-led transition in the near-term, some of the technical complexity will be resolved, but the market chaos will not. Ironically, an aggregator will eventually be needed to provide orderly and viable long-term market solutions to serve a much broader range of customers.

One clear choice?

When you consider the future of the electrical utility industry in terms of these two paths, you realize that we are ultimately headed towards one similar future – one of increased complexity and higher order. It is human nature to seek to establish some measure of order out of chaos and complexity. However, it is also human nature to become impatient and dissatisfied with inefficient methods of doing business. Speed appears to be the primary driver motivating the near-term direction of external markets. If a market-led transition is pursued, it will be driven because the market and customers are ready to lead and move forward before utilities are ready to do so. One of the problems with making near-term decisions that are built upon speed as a functional driver is that long-term implications are likely to be overlooked. One of the most important of these long-term implications is cost.

Although there are many factors involved with heading in either direction, one high-level conclusion emerges that can be explained by simple geometry. The three arrows from the previous diagram form a triangle. Mathematically, when the hypotenuse and one side of a triangle are added together, they will always be longer than the other remaining side. Although the individual lengths of each side of the triangle can be debated, the end result remains the same: If we first pursue a market-led transition, we will all collectively have to travel a greater distance to reach a related end state. The most obvious implication is higher cost. A future that is led by a competitive market seeking profit margins in the near-term, followed by mergers and acquisitions in the long-term, will likely cost more. Although a few corporations would benefit, all of us will collectively pay more as energy consumers.

Alternatively, if a utility leads in a proactive Utility 2.0 direction, they will do so with inherently higher grid system order and organization. Also, this by no means implies that the utilities will do this perfectly, or that market competition is eliminated or lost. In fact, part of what defines an effective utility-led model is the degree to which effective partnerships are leveraged. Simply put, electric utilities do not have adequate resources to master, track, and administer various DER customer solutions in an isolated manner. If utilities choose to embrace their role as a Utility 2.0 leader, greater visibility and clarity will be provided, which will help to bolster competitive markets. External markets become more cost-effective when they are given clear directives and defined time lines, and are provided with secure funding sources.

So isn’t the first choice – a utility-led transition – the best path forward? Not everyone believes this to be the case. A utility-led transition is perceived to be the slower path, due to the type of utility alignment required at the legislative, regulatory, and organizational levels. This is certainly a viable argument in the short term. However, is this a sound argument when considering the long-term direction of the industry? If we end up moving to a higher state of order, will it really be quicker to first be led by the market and then by a separate aggregator? The other observation that should be made is that not all utilities will opt to lead. In those cases, the market will lead by default, simply because it is the only remaining option. Some utilities may transition their business focus to exclusively become a “wires-only” company. For some utilities, this may be the preferred strategic pathway, while for others this may come as a result of following a market-driven direction.

Moving forward

So how do we best leverage the advantages that both the electric utility industry and the evolving external energy markets provide? How do we move forward in one cogent and unified direction? I think the answer to this question depends on the role one currently plays in the energy industry. Below are some thoughts that pertain to the three main entities associated with a Utility 2.0 transition.

Electric utilities should proactively lead the Utility 2.0 transition by developing a clear vision, strong guiding principles, and a tangible strategic framework. Utility 1.0 principles of low cost, reliability, and safety should not be abandoned, but they should also not serve as a justification to resist progress and change. Utilities must become more savvy in terms of customer service, in enhancing operational DER capability, and by demonstrating a new level of financial prudence that includes value-driven metrics and the exploration of new revenue sources.

Utility regulators create an environment in which both electric utilities and DER solutions providers can thrive both collectively and independently. In other words, develop a construct in which both utilities and external markets have the option to either collaborate or to forge independent paths. Doing so will create an open platform that both encourages collaboration and enables competition. If utilities are resistant or slow to move, DER solutions providers are given a means to independently succeed. Conversely, if DER solutions providers are resistant to mutually beneficial collaboration with utilities, then utilities will be able to thrive with or without their additional assistance.

DER solution providers continue to develop near-term solutions that grow market visibility and cater to various energy customer segments. Additionally, they should seek long-term partnerships with electric utilities and utility regulators based upon a foundation of trust and demonstrated market growth. Essentially, establish a firm market share that is not exclusively dependent on electric utilities and utility regulators, but also one that patiently and continuously seeks to thrive in the context of a future electric utility partnership.

As you can see, each entity can take near-term steps while also positioning themselves to consider more effective long-term partnership opportunities. The exact path we will collectively pursue is uncertain, but what is clear is that we must not lose sight of the long-term and overarching goals associated with shaping a Utility 2.0 future. We are seeking to modernize the grid in a manner that is the best for the energy user. In other words, in a way that is best for us all. This is done by continuing to focus on the bedrock principles of keeping costs as low as possible, maintaining high reliability, and ensuring operational safety.

However, it also means that the grid must be modernized in a manner that increasingly focuses on the customer perspective, incorporates greater degrees of financial flexibility, and is more technically coordinated and sophisticated. If we lose sight of these larger goals by actively or passively seeking industry silos, the majority will suffer. No single entity has all of the answers or solutions, but a clear path to future success can be paved by seeking greater industry collaboration. The pathway towards Utility 2.0 will be a complex journey, but the most efficient and cost-effective way to get there can be accomplished by forging mutually beneficial partnerships that keep the best interests of society in mind.

Author: Neil Placer

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.