The latest revision of the EU Directive on Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) was published in July 2012, and in some member states it took up to five years to transpose it into national legislation. The directive concerns all kinds of electronic equipment. So from a PV perspective, the delay did not affect the industry substantially. Today, however, it is the main legislation guiding the recycling of PV modules throughout Europe. And the debate as to its efficacy has intensified, with stakeholders arguing for bolder policies to ensure the sustainability of the sector.

The transposition of the EU directive into the national laws did not happen in one go. So while the directive’s main principle is to place an extended responsibility on manufacturers for end-of-life management of PV panels that remains the same across all 27 member states, implementation varies from country to country.

The main reason for such variation is that firstly the WEEE Directive distinguishes between private household or business-to-consumer (B2C) transactions and non-private household or business-to-business (B2B) transactions when mandating a financial mechanism for the collection and recycling of PV panels.

Secondly, the directive is flexible on the responsible party (owner or manufacturer) and financing methods. Therefore, whether a member state has characterized the PV panels as B2C, B2B or dual-use equipment, the financing requirements for the collection and recycling of the PV panels vary. France, for example, took its own approach, leading to a B2C characterization in the sense that it requires every PV manufacturer to pay a fee for the collection of the panels. In B2B transactions, both the owner of a project and the PV manufacturer may be capable of collecting and recycling end-of-life panels, and each member-state determines the financial responsibility of stakeholders. The bottom line is that member-states typically operate municipal collection points where B2C panels can be dropped off, while B2B equipment needs to be collected via an established scheme. At present, there are about 25 different compliant collection schemes in the European Union.

Typically, the compliant schemes operate the logistics: picking up the PV panels from the collection points. They have contracts in place with recycling companies that take the modules and recycle them. But collection schemes across the EU also vary substantially. Thus, Germany for example has about 10 different collection systems, Spain and Italy have about five schemes each, while France has only one such scheme in place, making it a monopoly.

The WEEE Directive follows a staged approach when setting the collection and recovery targets, but from 2018 onwards the directive calls for 65% of all electronic equipment put on the market each year to be recovered. Since PV panels have a much longer operational lifetime than many other electronic products, this is unrealistic. So, the directive allows for an annual 85% collection rate of the actual waste generated from PV panels. Similarly, from 2018 and beyond the directive sets an annual 85% recovered, and 80% prepared for reuse and recycled photovoltaic equipment. These targets apply for each member state individually.

Room for improvement

The numbers behind these targets are satisfactory, argues Andreas Wade, the global sustainability director for thin-film PV manufacturer First Solar. “What needs to be improved is the specification of the recovery and recycling targets,” explains Wade. “As it stands today, it is easy to fulfil the WEEE Directive requirements by recovering just the glass and the aluminum. This is a rather one size fits all approach. However, one has to ask what happens with potentially environmentally sensitive materials used in PV panels.”

Wade’s main argument is that the regulators need to enable high-value recycling of solar modules that also targets material with a high carbon footprint or high embedded carbon. “If you are able to recover energy intensive materials such as silicon, and if you are able to implement some recycled content in the new end product, then you can effectively lower the environmental footprint of the new PV panels,” he says.

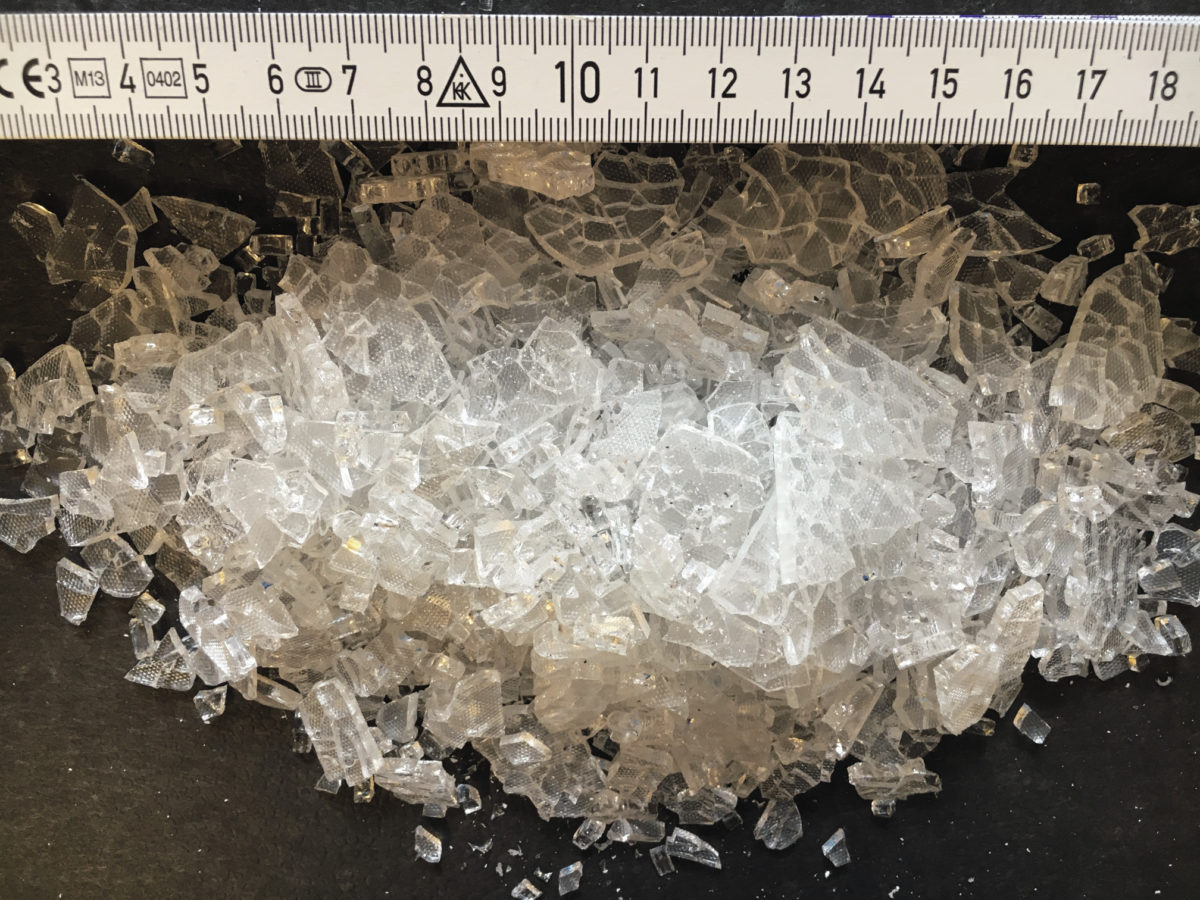

Wolfram Palitzsch, the CEO of LuxChemtech, a German firm that recovers and recycles materials found in PV panels, agrees with Wade. “Too many valuable materials [in the PV panels] are lost simply by fulfilling the [recycling] quota through glass. This has to change,” he argues. Palitzsch also provided another viewpoint on the PV recycling business: “If you look at photovoltaic waste, it is clear that the main mass [of recovered material] is the glass. However, this glass has to be transported, both as waste and as secondary raw material. We have demonstrated how you can produce completely clean secondary glass from PV scrap, but unfortunately the transport costs limit everything,” he says. “If you able to extract the materials that are much less common but have a higher value, things will look completely different.”

Wade addresses the topic of valuable materials also. Next year in the upcoming Eco-design Directive, the EU Commission has an opportunity to make the PV panels more sustainable by introducing recycling component criteria, such as for every PV panel installed in the EU market, a certain amount of glass, aluminum, silicon and other material should be recovered and recycled. “If this is implemented, the equation can be turned the other way around. Certain components will acquire value in the market and would be in demand by the manufacturers who will need them in order to place their new panels in the EU market.”

Moreover, by using market pricing mechanisms and enabling high-value recycling, the European Union will also trigger recycling companies to develop new technologies to recycle the non-glass materials. These kinds of companies need regulatory certainty and this is why the EU needs binding targets for the recovery of specific elements in solar PV panels, adds Wade.

Palitzsch tells pv magazine that LuxChemtech processes a lot of waste generated in the production of modules and recycles silicon, silver, indium, tellurium and other materials, indeed most materials from the module production chain. LuxChemtech has signed non-disclosure agreements with PV manufacturers and plans to build a new factory, but equally the firm sees upcoming challenges. “There is currently a lack of reliable material flows that would secure annual operations for an investor. After all, it is of no use if you set up a recycling company that does not work for half a year due to lack of input,” says Palitzsch. He appears positive, however, for the next years, arguing that “the necessary quantities of old PV modules” will need to be recycled, justifying LuxChemtech’s business plans.

Sustainability mechanism

Asked about France’s policy to incorporate carbon content criteria in the allocation of the winning projects in the French solar PV tenders, Wade remarks that, as it happened, this was an elegant way for the French administration to promote the country’s local industry.

The carbon intensity of electricity is crucial when you manufacture PV panels, because producing solar grade silicon is energy intensive, and in France the energy mix already has low carbon intensity due to the dominant nuclear energy sector.

Wade accepts this argument, however he also adds that the French scheme has now evolved, providing a very good example of how a market based mechanism can lead to improvements in the sustainability of products. So, says Wade, “if you look at the [French] tender results you will see the difference between firms who manufacture in France and overseas has levelled out, because manufacturers found ways to address the carbon requirements of the tenders, either by switching to renewable electricity supply, or by using recycled content.”

Wade adds that if France aims to reduce the carbon footprint of its electricity grid in order to meet its climate objectives, then it must also carefully evaluate what kind of technologies connect to its grid. “They need to deploy low carbon energy technologies. This is a new perspective on the front of carbon footprint criteria in competitive tenders, and is also a very elegant way to tackle the sustainability initiative upstream by enabling a market mechanism that provides for the remuneration of sustainability,” says Wade.

EU leadership

Nevertheless, Wade is optimistic. The reason is that the quality of PV recycling is entering the public debate. “I see the quality, and not only the quantities, of the recycling being widely discussed now in Germany and France, while the debate is also picking up in Spain and Italy,” he explains. “Which makes sense because these are major photovoltaic markets that are maturing, so they need to address the PV recycling issue.”

In fact, the European Commission has also addressed this issue by hiring an external consultant to examine all the WEEE Directive transpositions in the EU member-states, identify gaps in the policy and suggest opportunities for improving the legislation. This process has taken the last three years and the consultant is about to issue its recommendation to the Commission.

But according to Wade, Germany and some other member-states feel the overall process is progressing too slowly, and want to step up the effort by legislating their own policies first. The European Commission definitely has an opportunity to lead the PV world again, this time by providing specific quotas for recycling PV panel materials.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.