Sabine Tischew, professor of plant sociology and landscape ecology, is here to be convinced. She announces this as she climbs into the car, where Ralf Schnitzler, solar project developer at Bejulo GmbH, is driving pv magazine and two other curious professors from the Anhalt University of Applied Sciences to Frauendorf – a two-hour car journey south from Berlin. Summer is drawing to a close and it is one of the last hot days of the year.

My notebook fills up as the passengers ponder integrating biodiversity concepts with solar parks: developing robots to mow under solar panels; the interaction of vertebrates with PV installations; the key to effective land management strategies.

Don’t judge a book

We arrive at Spreegas Solar’s 10 MW Frauendorf Solar Park, located in southern Brandenburg, punctually at midday. Easing out of the car, I must admit I have to contain my disappointment. Rather than the bright bursts of color and willowy wildflowers swaying in the breeze that I was expecting to see, there sits instead a humdrum solar park, tufts of grass and brownish, dry vegetation sparsely dispersed throughout.

“It looked quite different a few weeks ago,” Christina Grätz, owner of Nagola Re GmbH and master implementer of the biodiversity concept here, assures me, as we gather with SpreeGas Managing Director Andreas Kretzschmar and Project Manager Jörg Schulze. Now I need convincing, I think.

My skepticism soon turns to wonder, however, as I’m forced to turn my attention to avoiding squashing the hundreds of grasshoppers that are seething underfoot. Hopping from side to side – a rather ungainly version of the insects – my gaze is pulled downward to the ground, which is alive with all manner of creepy crawlies.

Three years ago, there was no life here, Grätz tells me. Indeed, the site had been used for intensive agricultural purposes, growing maize, and soaked in pesticides. Other than a few weeds, nothing had dared take root and there were certainly no insects around. Since the solar park has been installed, however, a plethora of flora and fauna are now thriving. The biologist – who is also Germany’s leading ant re-homer – is hands-on in the most literal sense, and marches off through the long grass bordering the solar installation. It hasn’t been mowed since last year to provide hibernation opportunity for insects over the winter. Not being a fan of spiders, I follow with some trepidation, cursing my shoes with their summery slits, as she lists the many endangered plant species and insect populations that now appear in abundance: meadow sage, carthusian clove, maiden pink, wild bees, honey bees, butterflies, ants, mice, caterpillars, eagles, deer, badgers. She stops and, together with the two professors who are walking around wide eyed and animated as they discover species after species, bends down to point out small holes in the earth where wild bees live. She then picks up a Bedstraw Hawk Moth caterpillar, which looks more like an extra from the film Alien, if you ask me.

Grätz’s enthusiasm is infectious, and I soon forget my initial despondency. If ever the phrase “don’t judge a book by its cover” was relevant, it is here. As she and the professors break off to admire yet more plant species, I head over to speak with Kretzschmar. Is he as enthusiastic as Grätz about the project? Does it make financial sense to partner biodiversity with solar parks? Of the five PV projects SpreeGas has installed since 2017, when it entered the solar business, four have integrated biodiversity concepts, says Kretzschmar. SpreeGas has worked with Grätz on each of them. He tells me that as solar developers have to take certain measures, such as planting trees or hedgerows, anyway, it makes sense to invest in building something that creates a positive difference to the surrounding habitat. It’s also a great way to involve the local community. Regional beekeepers have set up honeybee populations here, for example, while schools are invited to visit. “We wanted to do something more for the environment and build a project that both scientists and children could make use of,” he says. “It’s a concept we expect to roll out across our other solar parks in the future.” It is evident he is proud of SpreeGas’s achievement.

Effective management

According to Grätz, the key to effective biodiversity management is creating concepts tailored to the specific sites. Soil type and solar irradiation will impact the types of plant and wildlife that are attracted. It’s also important to regularly monitor sites, she says, so strategies can be adjusted. What may make sense on paper, may not take root on location, and surprises may occur in the form of unexpected species turning up, she says.

I speak with Wychwood biodiversity consultant Guy Parker, who works on similar projects in the United Kingdom, after the site visit. He believes it is possible to roll out more generic biodiversity plans, which will bring some environmental improvement to a site. Wildflowers like red clover, for example, are able to cope with many different types of soil and weather conditions. “You can sow them on all solar farms and get a little bit of improvement in terms of the number of bumblebees and butterflies,” he says.

Renewable energy company Anesco is also busy building solar farms with integrated biodiversity concepts. The firm’s technical support and consultancy director, Sarah Hitchcox, tells me its strategy is to create landscape and biodiversity management plans focused on supporting wildlife that are most under threat. Bringing in the local community is also key. “This may include adding bird and bat boxes, and planting wildflowers and specific shrubbery that is designed to support species under threat,” she says. “The cost of these enhancements is very low and they are also very easy to do. It’s really a no-brainer for any developer and maintenance team.”

Data collection

And monitoring is essential. Parker and his team have five years’ worth of biodiversity data on some of their sites. This has helped shape more effective management plans, he says. “We started off thinking entire solar farms should be wildflower meadows, because you maximize the use of land. However, we found that quite difficult to manage. Having wildflowers around the edges and in the void areas worked really well though.” Overall, he says they’re reaching a point of understanding where the most feasible point lies between the cost of doing something and the benefit it produces, and how to combine this with solar farm management.

Using this data, Parker – together with colleagues at the U.K.’s Solar Trade Association and National Farmers Union – has developed national guidelines for biodiversity management. The aim was to provide simple, evidence-based examples to build up diversity within a site. “We’ve borrowed heavily from the agriculture environment schemes in the U.K. – having hedgerows to protect breeding birds, pruning or cutting vegetation every two to three years in winter, only cutting one side of the hedgerows, identifying areas within a solar farm suitable for wildflowers, allowing grassland to grow between the hedgerows and security fence, which is really good for wintering birds and insects, as well as having good foraging habitat in the summer, building small ponds, installing bird and bat boxes.”

Clarkson & Woods, also located in the U.K., has begun publishing annual surveys on its ecological monitoring of solar sites. The first was released this July and included data from 59 projects across the country. “In total, we recorded 41 different grass species and 195 other plant types. This included five different species of tree saplings, bramble or dewberry growing within the arrays on 40% of sites. This monitoring gave an advance warning of potential problems arising from woody growth under/around the panels and the need for amending management practices,” the company says.

Anesco’s Sarah Hitchcox says the data the company has gathered has also recorded many positive impacts. At a site where the grass grows rapidly, they’re trialing a flower called yellow rattle, which is not only local to the area, but stunts grass growth – thus reducing the frequency with which it needs to be cut. “At another one of our sites there are now lapwings nesting and breeding. This is great news, as lapwings have suffered significant declines and are now a Red List species, meaning they’re globally threatened,” she says.

The birds

At the Frauendorf site, Grätz has yet to collect data on how solar installations impact birds, which is an area Tischew is particularly intrigued by. While there does not appear to be much information on the subject available, according to the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, “Climate change and land,” in many “regions around the world, wind turbines and solar farms pose a threat to many … species especially predatory birds and insectivorous bats … and disrupt habitat connectivity.”

I ask Anesco, which has worked together with the U.K.’s Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, what its data has shown. “PV plants don’t pose a threat to birds and we believe our work in this area has shown they in fact provide a perfect opportunity to support wildlife,” says Hitchcox. “Unlike other types of development, which may require trees and hedgerows to be cut down, at our solar parks we will plant more trees and bolster hedgerows, as well as create habitats around the solar panel modules themselves.”

Parker has also not recorded any detrimental effects to birds on his sites. “That’s not to say they’re not out there, we just haven’t seen them,” he says. He and his colleagues have collected breeding bird surveys in the spring and summer. “Repetition over time shows that where we’ve put wildflower meadows, there has been a small increase in the number of birds and certainly not any decrease.”

A no-brainer?

It seems planning solar parks with integrated biodiversity concepts kills two birds with one stone. In addition to serving the clean energy transition, projects boost environmental benefits, such as reversing soil erosion, supporting collapsing insect and bird populations, and bringing local communities together.

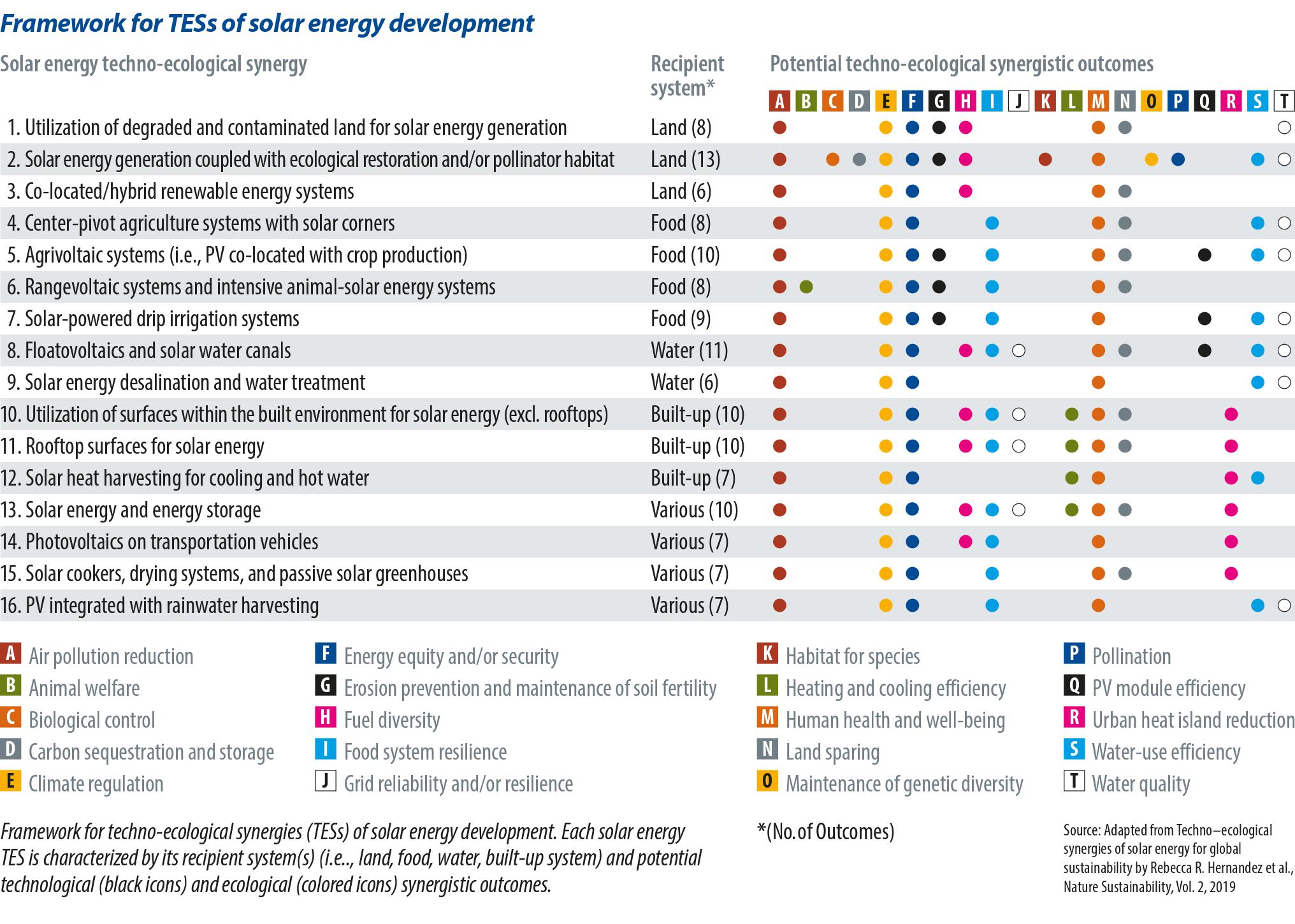

In the first peer reviewed paper of its kind, Nature Sustainability’s “Techno–ecological synergies of solar energy for global sustainability” report provides further evidence that such projects can bring a myriad of benefits. The authors identified 16 techno-ecological synergy benefits of installing solar energy. The one which created the most advantages – 13 – was solar coupled with ecological restoration and/or pollinator habitats (see chart below and read a guest article from the authors).

While the IPCC was less enthusiastic about solar farms in relation to birds, its report does highlight their potential to help address climate change: “Land-based responses to climate change can be … adaptation with mitigation co-benefits (for example, siting solar farms on highly degraded land).” It also references studies published in Science in 2018, demonstrating that large-scale wind and solar farms in the Sahara increased both rainfall and vegetation.

While the IPCC was less enthusiastic about solar farms in relation to birds, its report does highlight their potential to help address climate change: “Land-based responses to climate change can be … adaptation with mitigation co-benefits (for example, siting solar farms on highly degraded land).” It also references studies published in Science in 2018, demonstrating that large-scale wind and solar farms in the Sahara increased both rainfall and vegetation.

It’s all connected in a natural, circular economy. If biodiversity concepts are integrated with solar projects, the evidence suggests that we’d be able to more effectively address some of the catastrophic problems we’re facing. The key barrier to achieving this is, as ever, political leadership. “It would be so simple for government to say things like ‘All solar farms should have a biodiversity management plan with a minimum of A, B and C. That kind of simple leadership would be a game changer,” says Parker.

Are you convinced?

As Greer Ryan, one of the authors of the Nature Sustainability paper, eloquently suggests, there’s something poetic about reclaiming lands damaged by fossil fuels or pesticides and using them to generate clean energy and rebuild habitats.

On the way home from SpreeGas Solar’s Frauendorf Solar Park, I turn and ask Tischew if she’s convinced of the benefits of integrating biodiversity into PV project development. Her answer is a resolute “Yes!” She’s now off to try to secure funding from the German government to roll out such projects in other areas of the country.

What about you? Are you convinced? Join the conversation – contact up@pv-magazine.com.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.