At Indonesia’s last parliamentary hearing at the end of May 2021, the director general of electricity at the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR), Rida Mulyana, said that the country would not approve new coal-fired power plants from 2025. This step was taken to increase the share of renewable energy in the national energy mix and reduce the country’s carbon emissions. The decision’s 2025 implementation includes exceptions for power plants that have already been financed or are already constructed. The plan is also in line with the intentions of the state-owned electrical utility company, Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN), which is now considering plans to close down several coal-fired power plants. PLN vice director Darmawan Prasodjo said that subcritical power plants with capacities of 1 GW will start to close from 2030. And by 2055, coal-fired power plant production exceeding 50 GW of capacity will be taken off the grid.

Key factors

There are several factors that triggered Indonesia’s coal exit plans. The country’s National Determined Contributions (NDC), related to the ratified Paris Agreement, target 29% of business-as-usual (BaU) conditions, or 41% NDC with international support. This target, though, is seen as insufficient to meet the Paris Agreement’s goal, with Indonesia therefore needing to plan more ambitious steps.

Cutting emissions from the two most polluting sectors, such as forestry (from fire clearing and land use) and power generation, are both significant. In addition to speeding up mangrove restoration, Indonesia has committed to responding to this challenge by cutting fossil fuels from its power sector altogether.

External factors are also playing a role in this exit plan, as direct investments in the coal sector have dried up. “Since last year (2020), countries such as Japan, South Korea, and even China – which used to be the biggest supporter of Indonesia coal investment – decided to limit their direct investments. This could cause financial difficulties for PLN in the near future,” said Fabby Tumiwa, executive director of the Institute for Essential Service Reform (IESR), a think tank in Indonesia.

Closing down 50 GW of coal-fired power plants still isn’t sufficient to guarantee Indonesia’s smooth sailing toward its net-zero emissions target. “The target [of closing 50 GW coal-fired power plants] is not ambitious enough. From IESR’s recent study, this plan can be pushed through before 2030 and it is not needed to wait until 2055,” added the IESR director.

In the meantime, Tumiwa suggested that the government could put into place 130 GW of renewables capacity by 2030.

“To speed up the process [before 2030] is possible, but there are several consequences that we need to be prepared for, such as compensation support for replacement costs for the developer,” added Chrisnawan Anditya, the director of the department of new and renewable energy at the Indonesian Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources.

Chrisnawan added that there are several PPAs between PLN and coal developers that include “take or pay” clauses in the contracts. This would make it more difficult to initiate an earlier shutdown if there is no compensation provided by the national government.

Generation gap

In 2019, the government planned to achieve a target of 35 GW of new generation. About 6 GW are still under discussion, lacking specifications for the type of generation. However, just 11% of this target is provided by renewable energy sources, with coal taking up to 60% of the capacity. When the exit from coal-fired power plants takes place, the sustainability of this 35 GW will be criticized. “The rest of the 6 GW are a big opportunity for renewable energy such as solar PV to kick in,” said Tumiwa.

“The 11% of renewable energy referred to the plan that was launched in 2015, when the price of coal was still competitive. At that time, the price of electricity generated from solar was still high, compared with the current situation,” explained Chrisnawan.

Regarding the country’s target for electricity from renewable energy sources, the MEMR director stated that the ministry is prioritizing the development of solar via a key policy revision. Unfortunately, this revision is still waiting for President Joko Widodo’s approval.

“We did the revision of the MEMR regulation on rooftop solar PV that increased the export price from solar (higher than 65%), increased offset durations, and simplified the application process. In other regulations, such as the Presidential Regulation on New and Renewable Energy, we also introduced a new feed in tariff, ceiling prices, and opened up more negotiations based on other renewable potential (peaker hydro, ocean energy, etc.),” stated Chrisnawan. “We also plan for a higher solar scale about 25 MW to 200 MW and to increase the capacity of floating solar.”

The MEMR predicts energy demand will peak in 2040. To fulfill the baseload when the coal-fired power plants close, the government is considering renewable energy sources and other options. “We consider also nuclear power as an adequate substitute for coal to fill the gap,” stated Chrisnawan. He added that Indonesia almost fulfills the requirements for nuclear establishment, but is still far from national consensus.

Legal basis

So far, the Indonesian government has not published PLN’s electricity supply and demand business plan 2021-30 (Rencana Usaha Penyediaan Tenaga Listrik, RUPTL), which includes the coal exit scheme. The RUPTL draft, which was to be completed earlier this year, was not yet finalized. The MEMR hopes that RUPTL can be accomplished as soon as a reference for domestic and international energy investors.

“We basically do not need a legal basis to close old power plants, such as Suralaya in Western Java, which has been operating for over 30 years. What now matters are the active power plants that are linked to state assets. The government needs to make sure this aspect does not cause any financial risks. For this type of specific retirement, we need a further presidential decree as permission,” said Tumiwa.

Solar opportunities

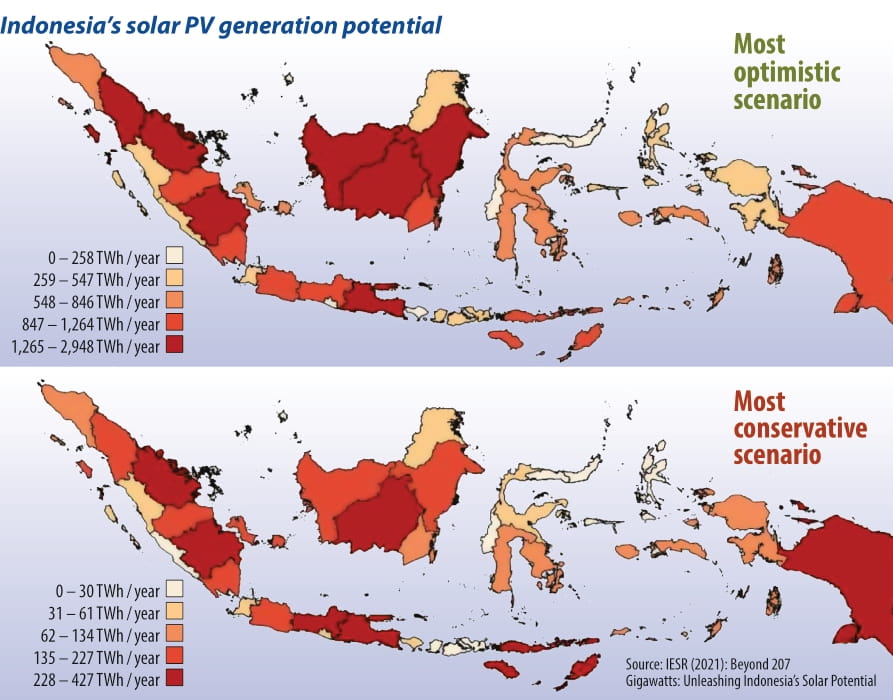

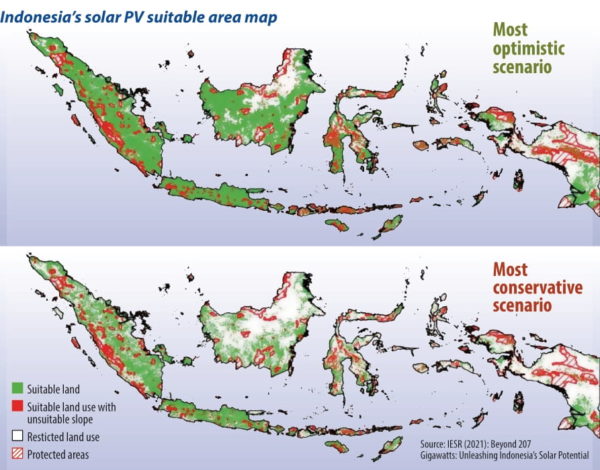

There is plenty of room for renewable energy to grow in Indonesia. PV could be the leading sector, based on its competitive price, the country’s geographical conditions, and possible areas of implications. IESR research shows that Indonesia, with its total land mass of 1.9 million km2, shows technical potential for PV that can reach a capacity of close to 20,000 GWp, in the best-case scenario. This prediction surpasses 2016 MEMR predictions which were at 207 GW. The stark difference in the data sets from the ministry and IESR comes down to the rapidly evolving technology.

“Renewables are so dynamic, this needs an update and is based on technical development – the last update the ministry provided was from 2016 in comparison to the IESR data that was released this year,” explained Chrisnawan.

The best scenario by IESR projects PV on a surface of 484.5 km2 covering all land types (forests, bodies of water, wetland areas, airports and seaports, and protected areas). The three provinces which seem to be the most promising are East Kalimantan (1.6 GW of capacity potential), Central Kalimantan (1.4 GW), and Riau (1.2 GW).

On the other hand, the weakest scenario was projected in agricultural areas, plantation forest exclusions, and dry shrub with 82.8 km2 of land mass. This so-called weakest scenario could even reach a potential capacity up to 3,397 GW. The top three provinces listed in this scenario are Papua (324 GW of potential capacity in 7,897 km2 land area), Riau (289 GW/7,059 km2), and Nusa Tenggara Timur (254 GW/6,203 km2).

The data provided by IESR does not yet include rooftop PV generators: 10 GW to 12 GW per year could be generated from rooftops alone.

“PV cost now is very competitive – it can be deployed at different scales – solar is a technology you can put almost anywhere. In our calculation we found rooftop solar can reach a minimum of 10 GW annually,” Tumiwa explained. “Utility -scale and large-scale commercial solar are also options.”

PV preparations

“Right now, we don’t really have a solar industry in this country. We have some module manufacturing, with about 12 companies operating a combined capacity of 500 MW annual production. In reality, they only produce less than 10% of their annual capacity due to lower demand in the past. But the state-owned company, Perseron Terbatas Lembaga Elektronika Nasional (PT LEN), plans to build a solar cell manufacturing company in Indonesia. This company plans to reach an output of 1 GW to 3 GW annually. This is followed by a number of companies with 1 GW to 2 GW capacity,” said Tumiwa on the future growth of Indonesia’s solar industry.

The MEMR also stated that they are giving active signals to the industry on growing solar markets. As Chrisnawan pointed out: “All components for solar are needed, not only the panel itself. We also care about the quality, so we introduced product standardization for photovoltaic silicon crystalline modules through MEMR regulation 2/2021, so the industry not only grows fast, but with assured quality.”

By Sorta Caroline

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.