A 1.25 kW rooftop array is small fry in today’s gigawatt-scale solar industry. However, one particular rooftop system in southern Australia may prove a big deal in the wider discussion about the right to sunlight.

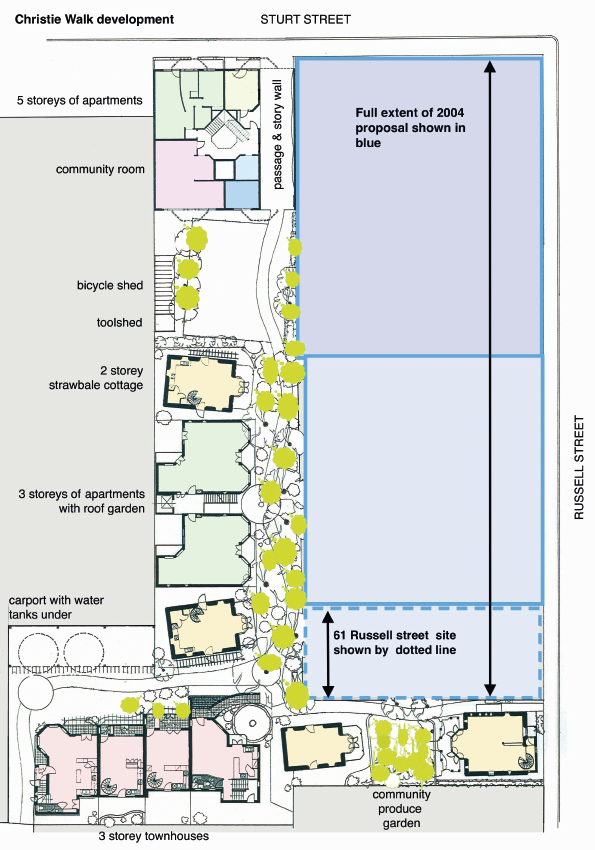

Josephine Thomas is a medical doctor and university lecturer in the state of South Australia’s capital city Adelaide. Her straw-bale home is a part of the Christie Walk ecological cohousing development in Adelaide’s picturesque city center. Christie Walk consists of Thomas’s home and two apartment blocks, in total 27 dwellings across 1,000 square meters. It’s home for around 40 people. Alongside the residential spaces, communal facilities, a rooftop garden, and community veggie patch are meeting points for the community.

“It’s a unique development in that it is central Adelaide,” describes Thomas. “Many ecologically minded developments sprawl out to maximize solar gains, but we are very compact on a rather unfavorable block in the middle of the city.”

In keeping with the development’s eco-living ethos, both apartment blocks, the townhouses, and the free standing straw-bale homes all feature solar PV and hot water systems. Given the limited space and curved corrugated iron roof on Thomas’s home, 205 W high efficiency Sanyo (now Panasonic) PV modules were installed. “It’s not a huge system, but we don’t have huge electricity needs,” says Thomas. Speaking of the curved roof, she notes: “It was really challenging to put anything up there.”

Neighbor throws shade

Given these challenges, and with the importance that the Christie Walk community places on low environmental impact living, when a property developer unveiled plans for a four-story apartment block next door Thomas and other residents were concerned.

“The initial plan was for a four story block, very standard construction maximizing the internal space and going up. Four stories don’t sound excessive but the surrounding properties are two stories, as is my home and the garden, and that is why we ended up embroiled in this dispute.”

The dispute Thomas refers to relates to the shading that the proposed apartment block next door would cast on her solar PV, solar thermal hot water, and the communal garden at the rear of her house.

“We went to [Adelaide City] Council to oppose the development on the basis of the overshadowing and because the new block would not be in keeping with the streetscape.”

The Council’s Planning Officer initially reviewed the development application and advised that it be given the go-ahead. Once Thomas and the Christie Walk community voiced their objections, the case was referred to the Council’s independent Development Assessment Panel (DAP), which adjudicates on such matters.

PV power

Thomas and the Christie Walk community built a case to take before the DAP. While things like amenities and aesthetics may be tricky to prove in a formal setting, solar PV produces data alongside electrons, meaning that the shading of her rooftop system became an important part of the community’s case against the developer’s proposal.

Local architect Julian Rutt, from firm Lumen Studio, produced some 3D modeling to help quantify the shading of the Christie Walk property, and Thomas’s rooftop array. The resulting shadow diagram (above) shows the PV modules, marked in red, are heavily shaded by the neighboring block.

To translate this modeling into electricity production data, Thomas turned to a solar professional – Sandy Pulsford with The Solar Project, Adelaide. Pulsford looked back through the inverter log, analyzed the impact of the shading, and came to the conclusion that the array’s daily generation would be reduced by 36%. On an average day, the system produces 5.3 kWh, with that increasing to 7.3 kWh in peak summer. While the impact on the PV was severe, the solar-thermal system’s performance was to be devastated. Pulsford was able to calculate that the solar hot water system would go from meeting 85% of Thomas’s needs, to a mere 6%.

Armed with this information, the Christie Walk group were able to make a compelling case at the adjudicating hearing, even avoiding having to fork out for a lawyer by representing themselves at the hearing. “The [DAP] commissioner was very reasonable,” explains Thomas. When it came to a final decision, the development application, as it stood, was declined. This was subsequently appealed to a higher court, and for a second time, the development application was turned down.

“I feel like the process has won,” says Thomas. “It has been effective in protecting our small solar array, [and] the [solar] hot water to some extent. But the garden is the big loser.”

A new plan for development has been submitted, with the fourth story now being set back from the property border, minimizing the shading of the PV array. The garden, as Thomas notes, will still be shaded to a large extent.

Growing issue

The right to protect an existing PV asset clearly played a role in the Christie Walk case in South Australia. And the wider issue as to how the future production of such assets can be protected in the years to come is one that is rapidly emerging in Australia.

With high electricity prices, subsidized rooftop systems, abundant sunshine, and home ownership commonplace, Australia has the highest residential rooftop PV penetration globally. In some states as many as a quarter of all households sport a PV array. And while the system on Thomas’s home is only small, average residential installation sizes today are around 5 kW.

“We’ve seen lots of examples where solar access comes up,” says Australian Solar Council CEO John Grimes. “The way that it is dealt with in Australia is not uniform and usually falls to local councils – the third tier of government.”

The Australian Solar Council (ASC) reports that some similar cases have emerged in recent months and that it is currently working to develop a set of principles that will guide its advocacy of solar consumers in the future. Grimes notes that there have been some promising developments regarding solar access in parts of the country such as the Australian Capital Territory, where every new development has what he describes as “mandated solar access rights.”

“Heights of fences and a whole range of things come into play when a development is accessed, [in light of] maximizing solar access.” Legally, solar access remains very much a gray area. The University of Adelaide’s Adrian Bradbrook investigated solar access in a paper published in an edition of the Western Australian Law Review, way back in 1983. Bradbrook, a legal scholar, was specifically addressing solar thermal systems for domestic hot water production; however, the principles apply equally to PV. While more than 30 years have passed since Bradbrook’s publication, very little has changed. In his journal article Bradbrook sets out that the only legal remedy for an occasion where a neighbor shades “solar collector panels” in Australia is under common law, whereby a complainant could apply under the principle of public nuisance. The exception to this is, as John Grimes from the ASC indicates, is the Australian Capital Territory.

The principle of public nuisance is only applicable in the case of solar access on the basis that “particular” or “special” damage can be proven to the individual, above and beyond that to which the development may subject the general public. Essentially, the affected individual, home, or business must demonstrate that the shading impacts them above and beyond any repercussions to the wider population. In the case of Thomas and the Christie Walk community, material “particular” or “special” damage could be proven, by way of the solar PV production data and its forecast decline.

“We were able to quantify the [PV] production,” explains Thomas, “and that makes for good evidence. We gave them three years of data and the shadow modeling. It’s pretty amazing from that perspective. It’s a small PV array, but it still stood up in court.”

The way forward

Looking to the future, it is highly likely that cases like the Christie Walk community and Jo Thomas’s house will become more common. The University of Western Australia’s Alex Gardner said that University of Adelaide’s Professor Adrian Bradbrook remains the lead legal author in the field in Australia, and he believes that it is a “potentially huge issue” in Australian cities.

“We have a very high uptake of rooftop solar panels and, so far as I’m aware, almost no legal protection of solar access rights,” says Gardner.

The Australian Solar Council is moving forward with its establishment of principals for such cases, however, CEO Grimes is charting a diplomatic course for the organization in relation to solar access. “Solar system rights trump development rights in every case? You can’t say that,” says Grimes. “It is a bit messy and will stay messy in the future. It does have to be assessed as to whether solar system rights trump development rights,” he notes.

The ASC chief reports that he is aware of three or four cases similar to the Christie Walk community’s in Australia and that he too expects more to come. The power of the solar data came to the fore in the particular case of Jo Thomas’s rooftop. However, the community garden was not spared from shading in the new application for development. Thomas reports that the developer himself has struck a much more conciliatory tone with his second development application, and has indicated he is willing to work with the Christie Walk community, rather than incur costly legal fees.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.