Turkey’s PV sector was late to kick off for such a sunny country. In late 2015, Turkey had installed only 248.8 MW of photovoltaic systems. According to the latest statistics published by Turkey’s ministry of energy and natural resources, the country’s PV sector added another 570.8 MW in 2016, which is an impressive 230% year-on-year growth that led to a cumulative figure of 819.6 MW of solar PV by the end of December. Turkish Solar Energy Society Solarbaba told pv magazine this figure has presently reached 860 MW and will most probably reach 1 GW in the very near future.

To view Turkey’s solar sector in full context though, it is useful to examine all recent data published by the energy ministry. The country added a total 5.9 GW of new power capacity last year, of which only 1.246 GW comprised solar PV and wind energies. The rest came predominantly via fossil fuel power plants (3.531 GW), while hydro plants added 789 MW and geothermal, biomass and waste power plants installed another 320 MW on top. Overall, Turkey's installed electricity capacity has now reached 78.49 GW and the national target for solar PV technology is 5 GW of installations by 2023.

Turkey’s new tender

All of Turkey’s PV installations belong to the so-called ‘unlicensed’ segment of the market, which concerns projects up to 1 MW of capacity each. More than one of these projects are often installed together, however each project holds a separate license.

The only exceptions to this rule are two projects installed last year in Eastern Turkey: an 8 MW solar farm in Elazig owned by local firm Akfen Renewable Energy and a 5.3 MW farm in Erzurum owned by Turkey’s Halk Enerji. The two projects belong to a separate category of 600 MW of large-scale PV been tendered in various phases in the past years. The farms at Elazig and Erzurum were the first to be tendered in May 2014, although the final license approval came in December 2014. More large-scale projects were tendered in January and April 2015.

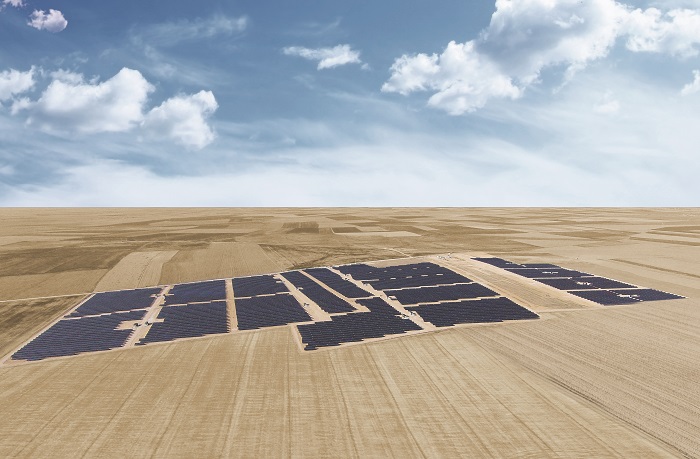

Last but not least, Turkey’s energy ministry has also announced a tender for a mega-solar 1 GW PV plant in Konya’s s Karapinar province in the centre of the country and the last ministerial information updated investors that bidding offers are postponed to 14 March, while the tender will take place on 20 March. The crucial detail though is that the new mega-plant needs to be built with locally manufactured components. Specifically, local manufacturing of PV modules, cells, wafers and ingots is mandatory, while the definition about what comprises a ‘local’ inverter is less clear, making the local assembly of inverters possible currently.

Based on data provided to pv magazine by Solarbaba, of Turkey’s 860 MW of current PV installations “at least 90 percent are using foreign modules (well-known top 10 1st tier modules), while what is more local is usually the construction and the mechanical parts of the projects.” Furthermore, there are also two or three plants with locally manufactured inverters, the Solarbaba data show.

Turkey’s government has been very keen to boost local manufacturing and the main instrument to do so was a regulation concerning the feed-in tariff (FIT) that the PV projects receiver for each unit of power they inject in the electricity grid. So, Turkey’s policy was that both the unlicensed and the licensed (or large-scale tendered) projects will receive a FIT for 10 years, plus five-year premiums for components (modules, sub-construction, inverters and cells) manufactured in Turkey. But this policy was scrapped at the end of 2016.

Local manufacturing

China’s CSUN is a firm that established a local assembly unit in Turkey with an output of 150 MW for solar cells and 500 MW for solar modules. Egemen Seymen, CSUN’s director in Turkey, told pv magazine that in the last three years CSUN has “supplied more than 70 MW of made in Turkey modules to the local market.” Furthermore, Seymen added, the company has also supplied the Turkish market with about 70 MW from CSUN’s factories in China and Vietnam. “But in 2017, it is difficult to import from overseas. So, we expect to deliver 100 MW plus made in Turkey modules to the Turkish market,” Seymen noted.

There is a confusion regarding Turkey’s policy on local PV manufacturing, the five-year premium for locally manufactured components and the import taxes for the foreign modules. Ates Ugurel, Solarbaba’s founder, provided pv magazine with great explanatory details.

Although the law for the five-year premium was cancelled only recently, the truth is it “was never put in action anyway,” said Ugurel. One reason for this, he suggests, is that investors did not use locally assembled modules because they were more expensive than the imported ones. Another reason, he added, is that investors “could not trust the quality of the products as they had no reference from the field.” Ugurel insists on the costs though. Building local manufacturing or assembly units in Turkey appears logical at first. To avoid anti-dumping and import taxes, some foreign manufacturers together with local Turkish companies are interested in establishing small sized assembly units. However in reality, such an investment decision is not logical, argues Ugurel, “because the product is 20 to 25% more expensive. This is the same situation as in the European Union (EU). Why did no one invest in local manufacturing in Germany, Italy or elsewhere? It doesn’t make sense at the moment unless you can invest in a ingot-wafer-cell-module manufacturing unit with at least 2 to 3 GW annual capacity.” Therefore, “the wiser approach at the moment [for Turkish projects] is to use Chinese modules and lower the LCOE for solar.”

Currently, Turkey applies an import tax (called gözetim vergisi) for all imported PV modules and also there is an anti-dumping investigation underway for all imported modules, and obviously Turkish projects that use locally assembled modules (like the CSUN Made in Turkey modules) avoid both.

Ugurel told pv magazine that the first stage of the anti-dumping investigation was completed in February and the relevant committee reported to the ministry of economy that it has detected a 27% dumping margin for modules imported from China. The whole process will be completed later in 2017, but given the forthcoming anti-dumping duty and the existing import tax, it becomes apparent why the government did not need the premium law anymore to trigger local manufacturing, said Ugurel.

Counterproductive experiments

The discussion leads naturally to the new 1 GW tender for the project in Konya. Why a foreign investor will want to build a local manufacturing unit to comply with the tender rules to be awarded the 1 GW project if the investment is pricey and there is not a strong domestic solar market? Should a Chinese firm want to target non-Turkish solar markets, they can already do so selling their modules manufactured in China, which are more price competitive.

In fact, Turkey’s government makes it harder for the domestic PV market to grow. One great example is the increase of the distribution fee that unlicensed PV projects pay to the local power distribution companies for transporting the generated solar power. This fee was TRY 0.0076 ($0.0021) per distribution unit in 2016 and increased to 2.56 kurus per unit in 2017 and 10.25 kurus per unit in 2018 (1 Turkish lira is 100 kurus and 1 USD is 3.75 Turkish liras). This was an indirect way to reduce the FIT for the unlicensed projects from 0.130 USD per kWh in 2016 to 0.126 USD per kWh in 2017 and to 0.103 USD per kWh in 2018. “That means almost the end of the non-licenced market as we know it,” said Ugurel. The change will not be apparent in 2017’s newly added unlicensed installations the existing awarded projects need to be built within two years from the time they were given the installation permissions. Therefore, we will see a rush of new unlicensed market installations in 2017. But the trend might be reversed in 2018.

CSUN’s Seymen expressed similar concerns to Ugurel on this front. Turkey has reached about 1 GW of installed capacity in the last five years mainly due to 1 MW unlicenced installations. “There are more than 7 GW approved and almost all of it is projects of 1 MW. I think more than half of this amount will not be connected to grid because of financial and legal problems.” Seymen added that there are also grid connection availability issues and lack of free capacity in transformer stations affecting the installation of approved PV projects.

Seymen and Ugurel also agree that Turkey’s rooftop potential is great but untapped. Legislation in the rooftop market is almost the same as utility scale installations, said Seymen, while Ugurel said that Turkey’s solar market needs a rooftop policy framework and new large-scale tenders if the country needs to sustain domestic demand for PV. Otherwise, the market can stall in as early as 2018.

Given these market conditions, it is possible that Turkey’s government has no genuine interest in solar technology. A deal for the 1 GW PV plant in Konya may be agreed with a Chinese investor in tandem with an agreement to build coal plants in Turkey. Turkey has announced plans to build as many as 80 new coal plants in the new few years on top of 25 coal plants it already has. Coal tenders are under way. The Konya PV plant could serve as an indicator of a populist agenda that is supposed to promote local interests, while in reality it hinders them.

Financing

As hinted by Seymen, finance is another obstacle faced by Turkish investors. The case is that Turkey’s banks have vastly expanded their portfolio during the last decade, due to the country’s impressive economic development and strong performance of the Turkish currency. But this is now a thing of the past. The value of the country’s currency has dwindled and Turkey’s economy has experienced a significant slowdown, with the national GDP growing approximately 4% in 2016, far less than the double-digit growth Turkey has seen in the last decade. Within this new environment, banks are struggling to finance new loans, while businesses are often unable to pay back their existing loans.

Andi Aranitasi, an Istanbul-based senior member of the Power and Energy team at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), tried to lower fears linked to the slowdown of Turkey’s economy. “Renewable projects in Turkey benefit from the country’s Renewable Energy Support Mechanism, where generators can sell their electricity via this system for a price per KWh fixed in hard currency (USD), so the loss of value in the currency does not affect the viability of the projects,” Aranitasi told pv magazine. In addition, electricity consumption has been growing at a good pace, 4.1% in 2016, and the EBRD understands Turkish banks have good capital ratio parameters and are still capable of financing new renewable energy projects, noted Aranitasi. “To illustrate this point, a combined €210 million was disbursed under both TurSEFF and MidSEFF (two EBRD schemes in Turkey) programmes in 2016, leveraging a further €140.5 million in investments. Investments under MidSEFF were all in the renewable energy sphere, while investments under TurSEFF concerned predominantly (unlicensed) solar PV projects.”

Aranitasi also appeared hopeful regarding the rooftop PV market. The EBRD has been co-operating with the Turkish government for a couple of years to develop a National Energy Efficiency Action Plan. Asked about it, Aranitasi said “the plan has progressed well and is in near final form. The government is finalising it. We hope it will be published soon,” and it “certainly includes measures to promote rooftop solar installations in industry and residential buildings.”

Aranitasi’s comments are in line with the bank’s steady stance in assisting Turkey to develop its renewable energy sector and supporting it with an abundance of funds, often being available via the EU. But its positive view strikes one’s attention for being so optimistic in a time that the country is evidently hit by political and economic problems. Fingers crossed, it will all go as Aranitasi says.

EBRD Schemes in Turkey

| EBRD Scheme | Financing information |

| TurSEFF | It has supported 205 MW of small-scale, unlicensed PV projects. These projects are either constructed or under construction.

The scheme received an additional €400 million funding boost in 2016. |

| TuREEFF | It mainly finances home energy efficiency projects but also the development of renewable energy systems in buildings. |

| MidSEFF | It supports renewable energy and resource efficiency projects.

In 2016, MidSEFF financed the first unlicensed solar PV power plants totalling 46 MW. In 2017, MidSEFF aims to finance an additional 120 MW of solar PV plants. MidSEFF also plans to finance two 20 MW and 7 MW PV projects. |

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.