From pv magazine 03/25

The hydrogen economy is complex. With photovoltaics largely devoted to directly decarbonizing electricity grids, solar-powered hydrogen is generally planned in remote areas with excess renewable energy. Getting beyond the hype requires understanding where hydrogen is essential to the energy transition. Government hydrogen strategies commonly identify green hydrogen as crucial for decarbonizing shipping, aviation, some long-haul road transport, ammonia and steel production, and other industrial processes. China also views hydrogen as essential for long-duration energy storage (LDES).

Hydrogen hyperbole

The last six years has brought what European hydrogen association H2UB calls a “peak of inflated expectations” and the “trough of disillusionment.” It says Europe is now entering a “slope of enlightenment,” before reaching a “plateau of productivity.”

Hydrogen makes differing contributions to “hard-to-abate” industries. While essential for decarbonizing steel, or the ammonia used in fertilizers, it plays a lesser if still crucial role in greening other sectors. That can confuse and polarize the green hydrogen debate.

China and more recently India are both moving forward quickly with hydrogen in their energy policies. Beyond climate change mitigation, these are aimed at reducing air pollution and follow a geopolitical strategy away from volatile global oil markets. Europe and other regions are also vulnerable to fossil fuel geopolitical stressors. Russia has abundant, easily extractable oil resources and is among the world’s largest oil exporters.

As the Energy Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Macroeconomic Research has shown (see chart below), hydrogen is expected to play a minor but crucial role in end-use energy demand through 2060.

Driving forces

Together, shipping and aviation are the primary drivers of hydrogen derivatives in so-called low-carbon fuels.

Shipping is ready to ramp up largely thanks to the European Union’s green fuel requirements. As with aircraft, fuel cells can power ships directly or via e-fuels such as methanol fuel cells. Most orders today are for combustion engines powered by green fuels, such as hydrogen-derived fuels.

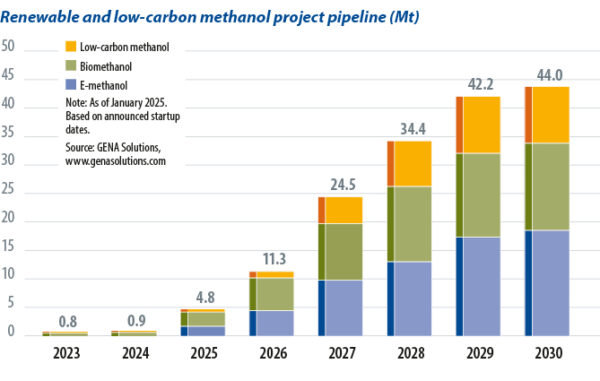

Vitalii Protasov, from Finnish renewable fuels analysis company Gena Solutions, said the European Union is driving regulation for shipping decarbonization, but noted the International Maritime Organization (IMO) is also expected to introduce mid-term measures in 2025, setting the pace internationally for increasing the proportion of low-carbon fuels.

Protasov said green methanol for direct use, unlike hydrogen, can be shipped as easily as fossil fuel-based methanol currently. The difference is in carbon intensity – and price. “The problem for [green] methanol is that there is a huge demand potential, particularly from the maritime industry, but the volume of binding long-term offtake contracts is very small,” he said. “There are also other problems, like high costs compared to the conventional fuel. So you need either a regulation that will stimulate use of renewable fuel, or some regulation that will prohibit or punish using conventional fuels.”

Aviation is arguably transport’s biggest decarbonization challenge. Batteries do not have sufficient energy density to power aviation beyond very local small aircraft.

Hydrogen can be used directly, for example, in short-distance fuel cell-powered aircraft, or it can feed the e-fuels used in sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs) and other fuels, as a substitute for limited organic matter. Most airlines have begun investing in SAF-powered flight in order to comply with recent regulations. Many have also invested in fuel cell aircraft, such as KLM, American Airlines, among others.

In the United States, newly merged regional carriers Alaska Airlines and Hawaiian Airlines have teamed up with hydrogen-electric aircraft company ZeroAvia to develop planes for short-haul routes. Diana Birkett Rakkow, senior vice president of sustainability at Alaska Airlines, explained that roughly 15% of the routes on the carrier’s network are under 500 nautical miles, meaning they can be served by hydrogen-powered planes.

Marina Hritsyshyna, a hydrogen regulation expert who has worked in renewable energy law since 2016, told pv magazine that “the regulatory framework is crucial, as it establishes a clear pathway for the development of the energy sector.”

The ReFuelEU Aviation and FuelEU Maritime regulations play a significant role said Hritsyshyna, who also cites EU targets set in RED III, the bloc’s third Renewable Energy Directive, for renewable fuels. This will require member states to fulfill specific quotas, “which will facilitate the growth of the hydrogen market,” said Hritsyshyna. “Simultaneously, the implementation of the EU ETS [Emissions Trading System] is expected to reduce the use of fossil fuels, driven by increasing carbon prices in the aviation and maritime sectors.”

Road transport

Hydrogen fuel cells have higher energy density than batteries, but poorer energy efficiency in smaller vehicles.

The hydrogen strategies of the United States, Europe and China all see some trucks and buses as use cases for fuel cell vehicles. Infrastructure plays a role here, as electric truck stops using batteries take as much energy to recharge as a small town. Trucking corridors create immediate demand from linked hydrogen-based-industry hubs, which already present workable business cases.

Reinhold Wurster, senior project manager at German consultancy Ludwig-Bölkow Systemtechnik (LBST), explained just how far China has progressed. With China’s last five-year plan targeting 50,000 fuel cell vehicles by 2025, Wurster said most of the 20,000 to 21,000 fuel cell vehicles on Chinese roads are trucks and buses.

“China has to introduce another 30,000 fuel cell vehicles this year,” said Wurster. “The figures I have seen for the different cluster centers seem to promise that this will be achieved. They want to have a more complete hydrogen technology innovation system in place, with clean hydrogen production and supply systems to be formed and this system should be matured by 2035.”

China’s big industries

The study “Enhancing a Just Transition Finance System for Carbon-Intensive Industries” focuses on the efforts underway to decarbonize China’s steel and shipping sectors. Commissioned by German political foundation Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, researchers from China’s Duke Kunshan University revealed that hydrogen is already entrenched in efforts to decarbonize Chinese industries, which produce around half the world’s steel and one-third of global shipping volume. The study gives the example of a steel company in Shanghai that has “effectively reduced its carbon emissions by 20% and cut solid fuel consumption by 30% through energy substitution, process optimization and the adoption of innovative technologies such as hydrogen-enriched carbon recycling blast furnaces.”

International pathways

There are limitations for hydrogen. Fossil fuels giant BP’s “Global Energy Outlook 2024” report found the “relatively high cost of transporting hydrogen, especially in its pure form, means that trade in low carbon hydrogen is concentrated in relatively localized, regional markets.”

For example, hydrogen production is powered by wind power in Nordic nations and by solar in southern Europe and the Middle East.

The United States, for example, has the advantage of having energy-intensive industry and plentiful renewables generation potential. It could become a hydrogen exporter.

Pipelines and storage

Hydrogen strategies commonly envisage pipelines for direct hydrogen transport between neighboring regions. Existing fossil fuel structures are often reusable for different aspects of the hydrogen economy. Governments hope to utilize existing gas pipeline infrastructure or build new ones. Wurster explained China’s foray into direct hydrogen storage and pipelines. “No country knows better where the limitations of batteries are,” he said. “Ten years ago, from Inner Mongolia, they built a high voltage direct-current transmission line of 1,800 km in 18 months, with 67,000 towers supporting the lines. So China is definitely a country that can build high-voltage direct current transmission lines rapidly. But one single pipeline, of 1,200 mm diameter, can transport 40 GW [of hydrogen]. This is 10 times what high voltage direct-current transmission line overhead wires transport today, which is 4 GW … nobody can ensure that the electricity being produced will be available at the time when the consumers need it, and vice versa, and above a certain limit you will not be able to store it in batteries anymore because it will be too expensive and too material-intensive.”

China’s hydrogen pipeline infrastructure is still in its infancy, Chinese media outlet Sohu.com said in January 2025. But the country’s industry development plan targets 3,000 km of long-distance hydrogen pipelines by 2030.

China is not neccessarily ahead of the European Union, the United States or the United Kingdom. Numerous studies have shown Europe has the potential to excel in different hydrogen technologies, but China is fast. If the West focuses too much attention on short-term political concerns, it will lose its competitive advantage.

Regulation expert Hritsyshyna points out, “It is also anticipated that the European Commission will adopt the Clean Industrial Deal and the Action Plan on Affordable Energy, in February [2025]. Additionally, the European Commission has presented a list of planned initiatives in the Competitiveness Compass, which aims to accelerate the deployment of clean technologies to achieve climate neutrality in the EU,” Hritsyshyna added.

What does all of that mean? It means that hydrogen economies are developing internationally. Short-term thinking will be a disadvantage on the international stage.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.