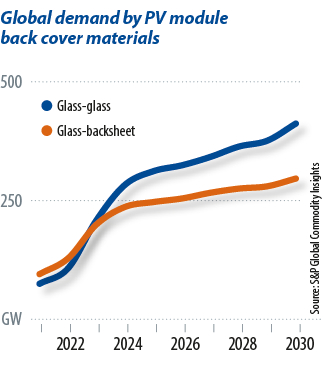

Polymer backsheets have received little attention in recent years, amid doubts about durability and limited transparent polymer options. Module makers have instead used glass on both sides, particularly in the large-scale project segment. Around 45% of modules currently being produced still feature backsheets, and while the trend toward glass-glass is set to continue, backsheet demand is reportedly rising.

“Forecasts indicate that the global demand for polymer backsheet materials will grow at an annual compound growth rate of 12% from 2021 to 2030,” said Karl Melkonyan, principal analyst for solar at S&P Global. “However, the overall share of all PV backsheet materials is expected to decline by approximately 3% per year during the same period, largely due to the rising trend of glass-glass modules.”

A recent change in backsheet material may have gone under the radar for many. Until 2020, backsheets typically comprised a core PET layer laminated with polyvinyl fluoride (PVF) or polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), but CPC products are replacing that option.

Three of China’s largest backsheet suppliers – Jolywood, Cybrid, and First PV Materials – confirmed to pv magazine that CPC products are now mainstream and amount to more than half of their backsheet sales, or more than 90% in Jolywood’s case.

The change has been rapid. Speaking at the European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference and Exhibition (EUPVSEC) in September 2024, Gernot Oreski, division manager at Austria’s Polymer Competence Center Leoben (PCCL), noted data estimating CPC-backsheet product market share rose from around 10% in 2020 to 50% in 2022.

That share is now likely larger, with Melkonyan stating that “recent market trends indicate that the share of CPC backsheets has more than doubled within a year.”

Manufacturers confirm that cost reduction is the main reason for the material switch. Cheng Xudong, general manager of Jolywood’s new material business unit, explained that laminated backsheets require additional adhesives and films, which have seen recent price increases and import restrictions. The lamination process itself also comes with additional costs. “Coated backsheets use fluorocarbon coatings as raw materials, which have a wide range of sourcing channels and are cost-controllable,” said Cheng. “Coated backsheets have a simpler production process, with lower investment costs for coating equipment and less energy consumption.”

CPC advantage

Backsheet manufacturers say that, aside from cost reduction, they see other benefits to using coated rather than laminated products. Cheng said that the adhesives used in lamination are often a weak point, as they are known to soften or debond under conditions of high temperature or humidity. He also noted that a properly applied and cured coating can form a dense structure on the surface of the backsheet while lamination can leave gaps between the two film layers, potentially allowing moisture and oxygen to reach a module’s inner workings.

Cheng added that CPC backsheets bring further advantages in terms of flexibility, since coating formulas can be adjusted to develop backsheets with performance characteristics to suit different installation environments and different base film materials can also be trialed. “By adjusting parameters such as coating thickness, hardness, and color, they can adapt to different climatic conditions and installation requirements and develop a more diverse range of backsheet products,” he said.

The Jolywood representative further noted that CPC comes with environmental benefits compared to laminated backsheets, since separating and recycling a coating and base polymer is much simpler than pulling apart laminated layers. They also offer a reduction in the use of adhesives and solvents and a thin coating consumes less material, and less toxic fluoropolymers, than a full additional layer laminated on top of a core layer.

Put to the test

PV researchers and industry observers, however, are now noting a serious lack of data to back up CPC performance claims. They have warned that PV manufacturers may have been reckless in adopting a new material in mass production without a full understanding of its performance in the many different climates and environments solar is being installed in. “The shift raises significant reliability concerns,” said Melkonyan. “The reduction in fluorine quantity and thickness compromises the protective qualities that are crucial for the durability of PV modules. As the industry pushes for cost reductions, the quality of materials may inadvertently suffer, leading to premature failures and safety issues.”

Backsheet manufacturers state that their CPC products are tested to and beyond the standards specified by the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). With backsheets in particular, well documented performance issues in the field show IEC tests are designed only to root out serious design flaws, not to prove long-term reliability.

Cheng said that Jolywood’s backsheets are subject to a range of tests including accelerated ultraviolet (UV) aging, humidity and heat aging, tensile strength, impact resistance, acid and alkali resistance, boiling water, and water vapor transmission. He further noted that tests exposing the backsheet to multiple stresses simultaneously could be useful in better understanding long term reliability. “To better simulate the environmental conditions that backsheets experience in actual applications, more complex stress tests are required,” he said.

Combined stress tests

Cheng noted that protocols exist for combined UV, temperature, and humidity testing, where modules are exposed to UV light inside a climate chamber, and UV/mechanical stress, where material is exposed to UV light and then subjected to impact, bending, or other types of mechanical stress. Earlier instances of widespread backsheet failure have led some in the industry to develop tests specifically designed to trigger failures and determine their likelihood in the field, such as combined accelerated stress testing created by the United States National Renewable Energy Laboratory, and module accelerated stress testing developed by DuPont.

Thus far, there is little to suggest that the latest generation of CPC backsheets has been subject to such tests. PCCL’s Oreski conducted a literature review of research into PV backsheets published between 2018 and 2023 and found that of 296 papers published during the period, just three mentioned CPC. “Analysis of the backsheet research revealed a significant misalignment between research interest and market reality,” he wrote in a paper summarizing the review. “Notably, the focus on materials like PVF, PVDF, and PA [polyamide] contrasts with limited exploration of double-sided coated backsheets.”

Thus far, there is little to suggest that the latest generation of CPC backsheets has been subject to such tests. PCCL’s Oreski conducted a literature review of research into PV backsheets published between 2018 and 2023 and found that of 296 papers published during the period, just three mentioned CPC. “Analysis of the backsheet research revealed a significant misalignment between research interest and market reality,” he wrote in a paper summarizing the review. “Notably, the focus on materials like PVF, PVDF, and PA [polyamide] contrasts with limited exploration of double-sided coated backsheets.”

Oreski has also found limited data available from manufacturers on the specific formulations of their backsheets, and their performance under different conditions. Of the data that is available, most come from smaller producers operating outside of China. That absence has Oreski and others working in PV reliability concerned. “I’m not trying to say that coatings are bad or that these backsheets are certain to fail,” said the researcher. “But we should have more tests and better understanding of a material before putting it into hundreds of gigawatts of modules.”

Oreski added that although plenty of manufacturers and third-party laboratories carry out testing to levels well beyond those specified in IEC and other qualification standards, few are doing long-term outdoor reliability testing.

Backsheet failure has had disastrous consequences for PV modules in the past. Problems with the triple-layer, PA-based “AAA” backsheets widely used between 2010 and 2013 are still being identified, with replacement costs estimated at more than $2 billion in Germany alone. Since manufacturers have different coating formulations and processes, it’s difficult to quantify the exact risks the latest generation of CPC backsheets brings. Oreski noted, however, that common coatings based on polyurethane or epoxy may be prone to moisture damage in humid conditions, and that big temperature swings and high UV light exposure have been factors in earlier backsheet reliability issues. Without test results, he said, “we are in a kind of limbo.”

Time and money

The cost and time required to conduct long-term combined stress testing likely explains the lack of CPC backsheet information. That data is needed to understand the performance and any associated risks. “Without the sequence of stress tests, we are bad at recognizing new failure modes,” said Oreski. “Often in PV, we have had big surprises after some years in the field, and all of us research institutes are running around trying to establish what’s happening. We need to test more and with combined or sequential stresses, to trigger all potential failure modes.”

The few studies that have focused on CPC backsheet reliability suggest that there may be reason for alarm. Researchers at the United States National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) subjected three CPC backsheets to UV light for up to 4,000 hours, simulating 45 years of exposure based on sunlight conditions in Arizona. “We characterized the chemical, optical, and mechanical properties of the degradation as a function of exposure time,” said NIST Materials Research Engineer Xiaohong Gu. “And we observed cracks in some, but not all of the samples we analyzed. These preliminary results indicated that some transparent backsheets also had cracking in the PET core layer.”

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.