From pv magazine print edition 10/24

The boys at the back of the bus were locked in debate about the prospects for Australian energy storage. In June 2024, on a tour of Shanghai organised by Australia’s Smart Energy Council, Tim Buckley, boss of think tank Climate Energy Finance, and renewables financier Oliver Yates were deep in discussion.

Yates was convinced batteries were poised to dominate all forms of energy storage, with Buckley musing that might have been the result of their visits to battery producer CATL and power electronics giant Sungrow. Yates, the first CEO of federal government-owned green bank Clean Energy Finance Corporation, has financed energy storage facilities. His prediction that batteries would outshine gas peaker plants and offshore wind in the supply of evening power was, therefore, notable.

Buckley agreed. “There’s been such a dramatic rate of technological improvement with batteries, coupled with scaling up, that any advantage other technologies may have had, to meet the evening demand peak, from five to six years ago is gone,” he said. “Batteries will do a huge amount more heavy lifting than even thought a few years ago.”

High volume

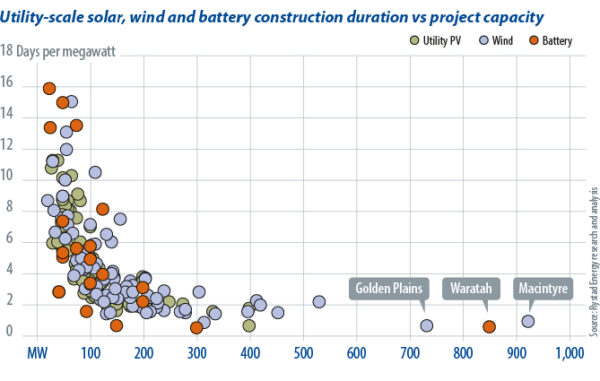

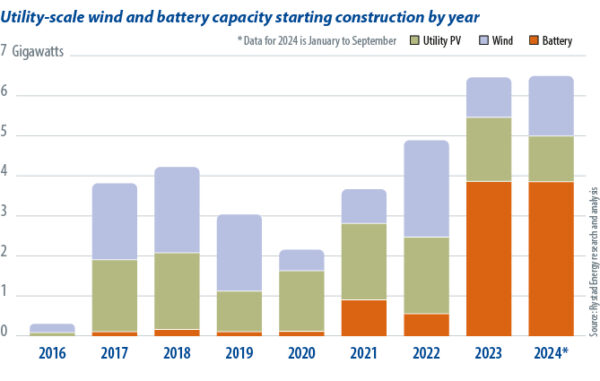

The volume of battery energy storage capacity connecting to the grid, being constructed, and reaching final investment decision confirms that thesis. Business intelligence company Rystad Energy has said that almost 4 GW of utility-scale battery energy storage systems (BESS) entered construction in the first nine months of 2024. That equals the full-year figure for 2023.

BloombergNEF has confirmed the rapid buildout of big batteries, recording 7.8 GW of utility-scale BESS currently under construction in Australia. It says installed big battery capacity will grow from 1.7 GW today to 18.5 GW in 2035.

The picture is replicated in mature renewables markets in California and Texas, where large-scale BESS have firmed electricity supply and evened out wholesale market price spikes.

Down Under, favorable economics for colocation with solar and wind power sites, the attractiveness of long-duration energy storage, supportive policy, and falling battery pack prices all support large-scale BESS growth. With the government targeting an 82% renewable energy mix by 2030, big batteries will be essential. Yates’ back-of-the-bus prediction looks likely to be proven right.

Long(er) duration

Australia’s big batteries are getting bigger, with storage capacities rising from one hour to two, four, and even eight hours, thanks to changes in battery revenue streams. Sites have switched from deriving income from short-term markets for grid-firming frequency control ancillary services (FCAS) to energy arbitrage – storing electricity when prices are low for sale during peak periods.

Energy economist Bruce Mountain confirmed that big batteries are attracting investors in Australia and capacities are growing.

“As a proportion of our peak electricity demand, we are level-pegging with California and Texas, with the rate of large-scale storage and we are seeing a similar increase in energy-to-power capabilities as they are seeing in those regions,” said Mountain. The director of the Victoria Energy Policy Center added that while these are positive developments, the volumes are not yet large enough to drive up increasingly depressed daytime wholesale electricity prices.

Outlining the development of the large-scale BESS market segment, from FCAS to arbitrage, Leonard Quong – BloombergNEF’s head of Australian research into energy transition and trade – said that a “tsunami of rooftop solar” and utility-scale solar has “reshaped power price dynamics in Australia.” As a result, he claimed, the arbitrage opportunity for big battery storage systems has become compelling.

“Across all of 2023, wholesale prices on the east coast were below zero around 9% of the time,” said Quong. “In some states, that was more than 25% of the time. So increasingly, batteries are being built to participate in the wholesale market to arbitrage prices. As a consequence, we’re seeing bigger batteries.”

Quong added that while attractive, the business model for arbitrage trading for batteries is “extraordinarily complicated and dynamic,” meaning that supportive policy measures remain important.

Rystad Energy numbers also confirm a trend of increased attractiveness for arbitrage opportunities. David Dixon, a Sydney-based renewables analyst at Rystad, said that most Australian states registered more than 1,000 hours of negative electricity prices in 2023, “with South Australia at 2,165 hours.”

Co-location the norm

The growing incidence of negative electricity prices is also driving the co-location of large BESS with PV and wind. With rooftop PV installations in Australia appearing to be settling at a volume of around 3 GW per year, and installation sizes expanding up to 9 kWp for each system, Quong’s rooftop “tsunami” has become an enveloping wave. Australia’s world-leading rooftop segment is cause for celebration, but it has created significant headwinds for large-scale renewables.

CIS delivery for big batteries

Think tank boss Buckley said that in a recent discussion with bankers from major institutions actively seeking renewable energy projects to lend to, he heard they were unable to locate suitable developments.

“Ultimately, the price volatility and the lack of long term PPAs [power purchase agreements] have made merchant utility-scale renewables projects [in Australia] virtually unbankable,” said Buckley. “Why would anyone build utility solar when your market is going to be eaten by rooftop solar?”

Fortunately, Buckley said, rapidly falling battery prices are making co-location with energy storage attractive.

“The dramatic cost reductions, 50% in the last 12 to 18 months for batteries, and [PV] module prices that are down 60%, have changed the game,” he said.

Coal closures

Australia remains heavily reliant on aging coal-fired power plants. In the most likely scenario of the country’s latest Integrated System Plan, the Australian Energy Market Operator projects that the lights will go out at the last coal-fired site by 2038.

Mountain, from the Victoria Energy Policy Center, said that when coal is finished – and it still supplies 55% of generation, year-round – there will be a lot of generation capacity to replace in the middle of the day.

“The nature of coal generation is that it is not flexible and has sizable start costs, meaning it bids in negative prices during the day,” Mountain said. “People talk of a solar glut but we are still miles from a solar glut. We still need masses of it and it is, per kilowatt-hour, the cheapest.”

Given the attractive long-term dynamics, BESS investors are seeing “an infinite horizon, relative to a starting point of new battery developments,” Mountain added, making such projects a relatively safe bet.

Former coal-fired power plant sites are already attracting large-scale battery projects due to their electricity infrastructure. AGL is building the 500 MW/1 GWh Liddell Battery Project in New South Wales, in May 2024 the state-owned generator in Queensland announced it was doubling the size of its Stanwell Clean Energy Hub battery, to 300 MW/1.2 GWh, and the Collie Battery in Western Australia is planned to have an eventual 1 GW/4 GWh scale, including a 219 MW/877 MWh first stage.

“The Collie big battery will be pivotal [in Western Australia] because suddenly people will realize that these big batteries work and work very well,” said Ray Wills, an academic with Perth consultancy Future Smart Strategies. “The experience is going to transmogrify the way that regulators see what is possible.”

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

1 comment

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.