In the rocky outcrops of Northern Illawarra beaches, an hour’s drive south of Sydney, the same coal seams that drew the attention of Australia’s first European settlers remain visible today. A little further south, in Port Kembla, flames from the long-running steelworks burn through the night, and yet the region’s gum-tree coated escarpment and picturesque shorelines feature on postcards.

In the rocky outcrops of Northern Illawarra beaches, an hour’s drive south of Sydney, the same coal seams that drew the attention of Australia’s first European settlers remain visible today. A little further south, in Port Kembla, flames from the long-running steelworks burn through the night, and yet the region’s gum-tree coated escarpment and picturesque shorelines feature on postcards.

These small working-class towns, cradled between mountains and sea, have drawn an influx of “sea-changers” in the last decade – among them some of Australia’s most prominent climate and energy transition spokespeople, including author Tim Flannery, inventor and entrepreneur Saul Griffith, and TV-star turned “just transition” advocate Yael Stone. They, and others, have pushed climate initiatives in the area, with the postcode 2515 even singled out to become Australia’s first all-electric suburb, although that pilot project’s funding is now precarious due to a recent change in government.

When the Electrify 2515 campaign began in 2022, led by Griffith’s decarbonization website Rewiring Australia, it sought to sign up 500 local pilot homes within three months. That goal was met in just three days. “We were blown away … everybody was really excited,” said Kristen McDonald, Rewiring Australia’s mobilization and engagement manager.

When the Electrify 2515 campaign began in 2022, led by Griffith’s decarbonization website Rewiring Australia, it sought to sign up 500 local pilot homes within three months. That goal was met in just three days. “We were blown away … everybody was really excited,” said Kristen McDonald, Rewiring Australia’s mobilization and engagement manager.

The Illawarra region has a long association with the energy industry. This, in combination with its port and transport infrastructure, and the vibrant conversation about the energy transition, have seen the region sanctioned as one of New South Wales’ (NSW) five Renewable Energy Zones. In August 2023, the federal government went a step further, proposing a 4.2 GW offshore wind development zone, spanning 1,461 km² of ocean, from Wombarra to Gerringong, 10 km to 30 km offshore.

Unexpected opposition

In the days and weeks that followed, social media erupted with outrage. Painted signs declaring “Not on our coast” were plastered in beach car parks and a series of superimposed images implying that wind turbines would appear like seaborne Eiffel Towers jammed up community groups on social media platform Facebook. It wasn’t until weeks later, in October 2023, that formal town-hall community consultation began. By then, misinformation had already flooded the discussion, creating a quagmire into which facts and figures from institutions including the local University of Wollongong and the Maritime Union of Australia, were often lost.

“The opposition took us by surprise,” Stone said. Four months earlier, she had launched the Illawarra initiative Hi Neighbour, focused on training coal-sector staff and young workers from other industries for renewable energy roles. Like Electrify 2515, the initiative was met with positive responses and support had been growing steadily but Stone’s visibility in the renewables space led to her being threatened during the peak of the wind zone fallout. “I was very naive about the community embrace of that,” she said, of plans for the wind farm. “I couldn’t have anticipated just how furious the debate would be … it was a shocking and scary time.”

Intermingled with inaccurately scaled images and loud opposition, however, community members also raised important questions about whether the money invested in the wind site, and the energy generated, would stay in the local area and, more importantly, who exactly would carry out the marine studies for the still-novel floating wind projects. That pointed to an evident conflict of interest, given project proponents historically lead such studies. I grew up in the Illawarra and the area’s famed whale migration was a part of our official primary school song. Whenever someone spied a humpback breach from our school window, class paused so we could all admire the procession.

Communities on this coast love its unique natural environment – something which holds true for many regions, with potato farms and rivers becoming embedded in people’s core identity. In the Illawarra, whales have turned into something of a proxy, with opponents of renewables development leveraging a real desire to protect beloved wildlife in order to shift the debate to blind fear. That has enabled right wing claims that wind farms will be “whale graveyards” to take root in an unwaveringly progressive region, the accusations spinning out of control online before calm counter-arguments can be made. “It gives me chills to see statements from Donald Trump echoed in our small town,” said Stone.

Rewiring Australia’s McDonald said that “what’s been hard has been to get across some of the nuances in the process that people should be directing their energy to.” She noted most renewable energy proponents share concerns about the environmental impact of large projects. “Instead, it’s been simplified a lot and the education side hasn’t been as strong as it should, so it whips up this kind of fear-based campaign and that plays on people’s uncertainties, which are valid,” she added. “As humans, we relate to what we can see and touch and feel, and sometimes it [climate change] is a little bit too abstract.”

Bush revolt

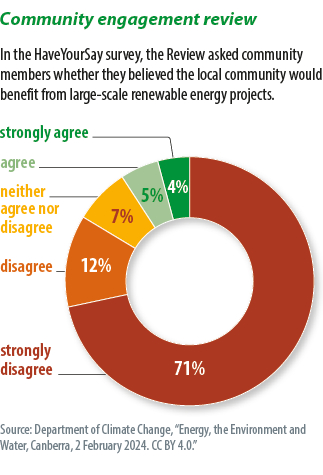

The emotionally charged scenes playing out in the Illawarra have parallels across the country, so much so that the phenomenon has been dubbed Australia’s “bush revolt.” Given large-scale renewables and transmission projects are set to ramp up massively over the next six years, thanks to new government procurement auctions, prime minister Anthony Albanese commissioned a formal renewable energy Community Engagement Review in July 2023. The findings from that exercise, led by Australia’s energy infrastructure commissioner, Andrew Dyer, were made public in February 2024 and painted a picture of a sector that is badly under-performing.

“For many developers, the skills, experience, and knowledge of engagement personnel and management are below community expectations, as are their supporting processes, collateral, and the overall governance of the developer’s engagement function,” the review read.

Dyer held scores of meetings with representative stakeholders, landholders, and community groups, and received more than 500 written submissions and more than 250 online survey responses – with most respondents living near to proposed renewables and transmission projects in development. Specifically, 92% of respondents were dissatisfied with project developers’ community engagement, and 85% were dissatisfied with the explanations and responses offered by developers. While the report focused on the private-sector clean power industry, it is worth noting that community frustration also extended to government-led renewables plans.

The review made six recommendations, all of which have been accepted by the federal government. They include instituting a “suitably qualified and experienced independent body or person to design, develop, implement, and operate a developer rating scheme.” Assessing developer practices and history, the rating scheme will launch on a voluntary basis but Dyer advised participation be considered in government tenders. He also recommended authorities begin vetting developers before allowing them to lodge plans outside auction programs. This practice is intended to cut down on the growing “consultation fatigue” being experienced by many communities, especially around Renewable Energy Zones.

Dyer urged states and territories to provide maps to set out where renewables and transmission projects are appropriate – including “no-go” zones – and to introduce a new ombudsman tasked with handling complaints during all project stages, with developers to bear the cost. The commissioner also recommended formal processes for community benefit sharing and communications programs – a theme that has been a focal point for Nicole Walton, principal for engagement and change advisory at Aurecon, a design, engineering, and advisory firm.

Building trust

Walton said that it is crucial that developers start by building trust. She posited a visualization that features an equilateral triangle in which empathy, authenticity, and logic must remain in balance. That means communicating in ways that recognize community perception, are transparent and clear, and recognize that different segments of the community will require varying degrees of information. While such an infographic may suffice for some, others will want technical project details in appropriate and digestible forms.

Winning community acceptance, Walton said, involves explaining a two-pronged narrative to help communities understand not just that the energy transition is happening but what it looks like at a state and local level. People must understand how projects benefit them, added Peta Ashworth, director of Curtin University’s Institute for Energy Transition.

The specific pathway to acceptance, Walton said, begins with ensuring communities understand the climate imperative. It should then turn to developers understanding community perceptions, putting a plan in place to address those beliefs, adapting that plan as they discover what the community specifically wants and needs, and then demonstrating they have responded to those local desires.

Finally, Walton said, it is crucial that developers resource and integrate their community engagement teams.

“The technical team relies on the community team to get that social license; the community engagement team relies on the technical team to have the content to win the social license – so they can’t operate separately from each other, although it is often the case that they try to,” she said. “Engaging the right people at the right time with the right messaging – all these things need to be considered and they are as important as your marine studies.”

She said they are as critical as flora and fauna studies, and they are as important as the design of the actual plant, “because without community acceptance, your project can fall over. It’s just that change in mindset.”

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

The problem is that nobody wants change, especially change forced on them.

Unless they understand the severity of climate change and its implications long term for all, they resort to not in my backyard paradigm. With such strong political divisions in all western democracies any common ground is almost impossible. The use of fear is the common go to strategy for any opposition to workable solutions. We have become so totally self obsessed as a society we no longer see the bigger picture

This is exactly the sort of thing that’s also happening all around the US right now. We have a well-meaning environmental movement that has spent years legitimately opposing oil/gas extraction and pipelines. And they say they want to get away from fossil fuels in general, without building new methane peaker plants and the like that the utilities seem to suddenly want more of: all well and good.

But when you start talking to these same folks about new mineral extraction needed for batteries, or placing a new set of power lines connecting proposed new wind or solar, or where those new generating sites will be, these same people automatically revert to NIMBY-like knee jerk opposition.

My thoughts are if someone with a supposed environmental agenda is showing up to demonstrate against new renewable energy infrastructure in their gasoline-powered SUV, driven from a house that’s fed by decades-old methane pipes plumbed into it for their heating and cooking, then they need to re-evaluate their long term environmental priorities. Unfortunately, climate change isn’t patiently waiting for everyone to get up to speed on this one.

It’s the scale of turbines that freak people out, if they were what we are use to seeing then the fear factor would disappate. New turbines proposed in our area are x2 of what we see in the distance . These over sized structures bring a hoste of issues, more impactfull than existing turbines.