Rystad Energy analysts recently expressed apprehension about a substantial surplus of unsold solar modules stockpiled in European warehouses. Rystad noted that in the first eight months of 2023, Europe imported approximately 78 GW of solar modules, a figure which surpassed anticipated installations for the entire year.

Import data to the end of September 2023, supplied by energy thinktank Ember, reached 85.9 GW [1] and the data beyond September 2023 is unavailable. Nevertheless, unless there is a substantial deceleration in deliveries to Europe, it is envisaged the module surplus may exceed 100 GW by year-end in 2023. Marius Mordal Bakke, a senior supply chain analyst at Rystad Energy, emphasized his concerns about the declining prices of solar modules in the market and the challenges associated with de-stocking older panels procured at higher cost. He underscored the necessity for the industry to adapt to shifting market dynamics.

Nonetheless, this development has provoked varying responses from other analysts, including Karl-Heinz Remmers, the founder of pv magazine. He has criticized Rystad Energy analysts, drawing particular attention to their inconsistency in estimating the stock of PV modules in European warehouses, with figures fluctuating between 40 GW and 80 GW. Remmers' primary contention appears to be that Rystad's statements may be generating undue alarm. He maintains that a surplus of PV modules in the European Union is a common occurrence. He emphasizes that EU analysts should embrace the notion that a warehouse stock ranging from 10 GW to 19 GW represents a “normal” inventory and should not be associated with the notion of “dumping.”

Remmers has presented three scenarios with the one EUPD Research finds most plausible as follows: With a 60 GW market in the European Union in 2023, “normal” inventory would run to 10 GW. Remmers estimates the European Union deployed 50 GW of module generation capacity to the end of October 2023 and posits a 59 GW module excess to the end of 2023, including stock carried over from 2022.

EUPD Research insists robust analysis must be contingent upon precise PV installation data. Our comprehensive assessments, rooted in years of meticulous data collection and monitoring of PV installations in our databases, necessitate certain adjustments to the figures put forth by various other analysts.

First and foremost, the 78 GW of Chinese PV exports to the European Union's 27 member states (the EU27) to the end of August must be considered with caution. The calculations were made by Ember, a London based independent energy thinktank. The General Administration of Customs of the People’s Republic of China does not release the generation capacity of its solar exports. Ember’s estimation was arrived at by dividing the export value of panels, in US dollars, by average monthly PV module prices [2]. When EUPD calculated the export capacity of Chinese products by using a methodology based on several data points, including module export weight, the figure fell to around 66.6 GW, reducing oversupply concern.

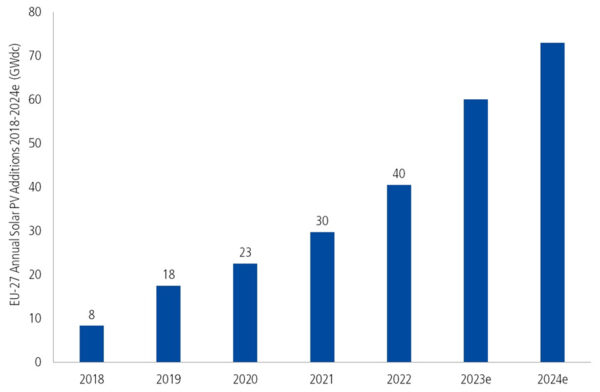

Additionally, there appears to be a miscalculation in the assertion that the European Union installed 46 GW of solar capacity in 2022. EUPD data [3] indicates the actual installation figure was approximately 40.4 GW, for the EU27, and 44 GW for the wider European market. Consequently, when considering that China exported 7 GW to the European Union in 2021, the surplus of Chinese exports from 2022 stands at approximately 47 GW:

Effective inventory management entails demand forecasting and EUPD expects the European Union to have deployed around 60 GW of solar generation capacity during 2023, almost 20 GW more than in 2022.

That would render the other two scenarios outlined by Remmers inconsequential – unless European energy authorities undertake significant retroactive revisions of their PV installation data during the first half of 2024. While the ultimate outcome remains to be seen, the 60 GW figure is based on EU27 third-quarter 2023 updates and the methodology of EUPD Research’s Global Energy Transition Matrix (GET Matrix) database [4].

EUPD Research's forecast for 2024 installed PV capacity ranges from 65 GW to 75 GW, depending on scenario. If Chinese solar exports to the European Union in 2023 reach 100 GW [5], that would bring an excess of 40 GW worth of panels shipped during 2023 to add to the 2022 surplus of 47.2 GW for total oversupply of 87.2 GW [6]. If a quarter of that figure (around 22 GW) is considered normal warehouse flow, the true oversupply runs to around 65 GW, similar to Remmers' 59 GW suggestion.

Is there oversupply?

Yes, there is. Zhang Sen, secretary-general of the photovoltaic branch of the China Chamber of Commerce for Import and Export wrote, in an article published on China’s Ministry of Commerce website, that, “Due to the optimistic atmosphere in the European market last year [2022] and the recent decline in European electricity prices, distributors have excess inventory.” Sen said, as the European Union is poised to install approximately 70 GW of solar capacity in 2024, it becomes evident that a chunk of 2024's PV installations will already exist within European warehouses at the onset of January 2024.

Furthermore, in conjunction with the data derived from the EUPD Research price and stock monitoring databases in Germany and Europe, as well as disconcerting feedback from various stakeholders, it could be concluded concern is real.

EUPD Research meticulously monitors the net purchase price of solar modules crafted from monocrystalline passivated emitter rear contact (PERC) cells, from the perspective of PV installers. It is noteworthy that these prices have reached historic lows. In the fourth quarter of 2023, prices for monocrystalline PERC modules from Chinese manufacturers are falling 30% compared to the first quarter of 2022.

While the lower prices generally reflect market developments over the previous two years, the reductions for Chinese manufacturers are particularly striking. For modules of the same technology produced by German manufacturers, the price decline over the same period was around 15%, only half the fall experienced by Chinese manufacturers. The persistent price fluctuations pose a particularly formidable challenge for installers who had made substantial prepayments to accumulate significant module stockpiles, anticipating extended delivery times.

Testimony from one such installer underscored the predicament. They told EUPD research, “The market has completely collapsed. Even the suppliers have cut their selling prices, by almost 50% from 2022 to 2023. We are the ones left behind because we ordered in 2021 for delivery at the end of 2022 so that we can work in 2023, and we will make huge losses this year. We are expecting a 75% drop in volume and a 50% drop in purchasing because prices have dropped so much. We are curious to see if we can survive that. And that's after 20 years of stability in the market and having weathered every solar crisis so far.”

This statement poignantly illustrates the issue of price erosion. In previous years, the primary challenge for installers was extended delivery times, prompting many to diversify their product portfolios and accumulate larger quantities of stock. However, those forward-thinking installers are now confronting the brunt of the challenge. Availability is no longer a major concern and market oversupply has driven prices down significantly compared to the previous year, when some installers made significant stock purchases.

Macro causes

The causes of the current oversupply are varied and include the solar learning curve, a need for the industry to be reordered, the fact Chinese manufacturers scaled much more rapidly than expected, and that those Chinese players could lose market share as attempts are made to onshore solar manufacturing.

The learning curve

Like any other technology, PV has to go through a learning curve. The solar learning curve refers to the process of continually reducing cost as more experience and expertise are gained in PV development and deployment. Swanson’s and Wright’s laws clearly describe how the cost or time required to perform an industrial task decreases as the task is repeated and experience is gained. Costs decrease and performance improves as industry gains knowledge and experience in manufacturing, installing, and maintaining solar systems. The price drops being experienced in the solar market today are primarily a phase in PV evolution that needs to be understood and managed.

Reshuffle

China Chamber's Sen has said the industry is poised for a transformation due to the recurrent issue of oversupply. In 2023, prominent photovoltaic companies including Longi Solar, JA Solar, Jinko Solar, Trina Solar, and Tongwei, have unveiled plans to expand production capacity. The expanded capacity predominantly focuses on negatively-doped, “n-type” production, known for its enhanced photovoltaic conversion efficiency. Notably, the n-type tunnel oxide passivated contact (TOPCon) technology route is the primary choice, although n-type heterojunction (HJT) technology is also in use. The expansion of those companies serves a dual purpose argues Sen – facilitating the rapid advancement of new technology and reducing production costs. However, it also accelerates the depreciation of photovoltaic equipment due to the excess production capacity, compelling enterprises to increase investment in back-end research and development and continually expand high-efficiency production capability to meet demand. Sen’s conclusion is that this, in turn, forces relatively lethargic small and medium-sized photovoltaic companies to exit the market.

Moreover, newer, more efficient modules mean faster installation with a smaller workforce required and, subsequently, higher margins. Put that in the context of an acute shortage of skilled workers in Europe and it would not be difficult to understand why such tectonic reshuffling of the industry, with a focus on new technology, is transpiring.

Production expansion

Chinese solar manufacturing capacity increased at a much faster pace than the PV market. As Chinese companies competed to have a bigger share of the market, Europe had to deal with basic issues such as supply (including critical material delays), and installation bottlenecks (including grid issues, and labor shortages). As an example, EUPD’s PV InstallerMonitor 2022/2023 found 63% of surveyed installers in Germany stated customers had to wait at least four months for installation after their initial contact. Although not as acute as in Germany, the situation was more or less the same for other major European markets.

Local support

Covid-led supply chain disruption, Russia's invasion of Ukraine, and increasingly ambitious climate change goals have mobilized the main importers of Chinese solar modules to kick off initiatives favoring local manufacturing. The most important destinations for Chinese module exports have traditionally been the United States and the European Union. Both these markets have planned, or are planning to further support their domestic industries via local manufacturing support policies. Legislation includes the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), in the United States [7]; and the Solar Energy Strategy aspect of the European Union's REPowerEU plan; Europe's Green Deal Industrial Plan, published in February 2023; the Net-Zero Industry Act (NZIA); and the Critical Raw Materials Act, both of which were published in March 2023 [8]. The European Union policies aim for 40% of the bloc's solar generation capacity in 2030 (around 30 GW) to comprise European-made components.

Furthermore, it should be emphasized that, as a consequence of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the European Union is adopting a more cautious approach to avoid placing exclusive reliance on Beijing for its solar energy initiatives. If China takes on the primary role in advancing green energy within the European Union, that would grant Beijing greater influence in key political decisions, displacing Brussels. European policymakers are thus striving to reduce their critical infrastructure dependence on China.

Oversupply response

From 2013 to 2018, the European Commission introduced minimum import tariffs on Chinese solar products to protect its domestic solar industry. That did not deliver a renaissance of European solar manufacturing, which experienced persistent insolvencies. The period also brought a bust in solar demand – it took several years for Europe’s solar installation rates to return to 2011 levels. Thus, one would think that the European Union would not again sleepwalk into such a blunder, especially as Brussels does not have the support of most of the solar sector which is responsible for almost all European solar jobs and revenues today.

Against such a background, and as Europe’s solar sector industry association, SolarPower Europe is recommending the European Commission amend EU state aid rules – the Temporary Crisis and Transition Framework – to allow EU member states to support European solar manufacturers with their operating expenditure costs. SolarPower Europe also wants “resilience auction” procurement exercises, under the NZIA, which would be earmarked for solely European made solar components. And the trade body has called for an EU-level financing instrument dedicated to European-produced PV – a “solar manufacturing bank.” [9]

Moreover, as each EU member state has a different solar ecosystem, it is highly likely each state will create special mechanisms to further support local PV production. The reaction of member states level is a matter to be determined in the coming months.

The canary in the mine

In the realm of the PV industry, effective inventory management in the face of fluctuating demand and prolonged lead times presents a formidable challenge. This challenge necessitates a meticulous and collaborative approach, recognizing that no singular entity operates in isolation within this dynamic industry. Instead, it is prudent for all stakeholders to adopt a holistic perspective, encompassing the broader business ecosystem. This comprehensive approach mandates decisions that not only bolster individual profit margins but also foster the collective wellbeing of interconnected companies.

Inherent uncertainty persists in demand, due to the perpetual evolution of technology. Consequently, it is imperative for manufacturers to engage in proactive collaboration with their clientele, gaining profound insights into the actual, attainable demand for their manufactured products. Additionally, an opportunity exists for suppliers, manufacturers, and distributors to participate in innovative and cooperative endeavors focused on the efficient recycling of unused components, ensuring their sustainable integration into the hands of end-users.

EUPD Research maintains a steadfast belief that the market will naturally self-regulate as the industry undergoes a transformative “reshuffling.” This self-regulation will occur in tandem with the stabilization of regulatory mechanisms, rendering them less susceptible to fluctuation. Simultaneously, different stakeholders will acquire a refined understanding of the rules governing their activity. It is evident that component manufacturers boasting exemplary back-end R&D will strategically prioritize shipments to regions where reasonable profit margins can be maintained, meticulously factoring in logistics and distribution costs. Conversely, markets characterized by a high risk of revenue loss will be approached with caution.

Within this intricate landscape, pivotal factors for achieving success encompass access to comprehensive market intelligence, the harnessing of invaluable insights from industry installers, the adoption of a strategically astute regional positioning, and judicious entry into the market with a meticulously calibrated level of investment. It is imperative to recognize that Europe constitutes a mosaic of distinct states, each delineated by unique political, economic, and environmentally sustainable strategies and prerequisites. The linchpin for survival and subsequent prosperity in the European PV market lies in the nuanced understanding of “what,” “how much,” and “when.” This is achievable exclusively through rigorous market research and data analysis.

Against this backdrop, EUPD Research extends the following resolute recommendation to the principal stakeholders in the realm of politics and industry, for the months ahead.

Punitive tariffs would severely impact the European Union's climate goals and job market, would slow down the PV industry as European end-customer and consumer costs would increase. With the European Union goal of achieving 42.5% renewable energy in its power mix by 2030 – which entails an acceleration of the PV deployment to 600 GWac by 2030 – solar is expected to create more than 1 million jobs in the European Union by 2025. Therefore, the reshoring of European manufacturing must happen with great caution and the right tools, so that the painful, fruitless experience of the 2010s is not repeated.

In the ever-evolving landscape of the European Union's renewable energy industry, navigating complexity and embracing innovation are paramount. The art of communication tailored specifically to target audiences will be key. Messages need to be created that resonate deeply, addressing the concerns and aspirations of diverse stakeholders within the renewable energy sector. Expertise in understanding the nuanced needs of installers, distributors, and other market intermediaries is required. By identifying and engaging with these key players, synergistic partnerships should be created that can drive meaningful progress.

Macro market intelligence will be vital in understanding global and regional trends, installed capacity figures, module prices, and the amount of PV components manufactured and exported. That would lead to a clear understanding of the top and emerging markets in each region, in the short and medium term and would help align supply and demand on a macro level.

In other words, and strategically speaking, optimized supply chains can ensure products reach the right place at the right time. That, coupled with a nuanced understanding of local markets, as micro market intelligence, will enable stakeholders to establish localized company presences that resonate with regional sensibilities.

At the heart of any successful approach in Europe lies a finely tuned brand management strategy. Compelling narratives that capture the essence of each renewable energy initiative must be created, along with adaptive strategies acknowledging the unique challenges posed by each European state. By employing country-specific language, cultural gaps can be bridged and a sense of connection that transcends borders can be fostered.

Finally, in a world where sustainability is not just a goal but a necessity, implementation of the right communication strategies, combined with comprehensive market knowledge, emerge as the catalysts for transformative change. The mission is to accompany business partners to thrive in the European Union's renewable energy industry. By aligning the right strategies with the pulse of local communities, impactful change is created which can usher in a future where renewable energy isn't just a choice but the cornerstone of progress.

[1] Please note that this figure is taken from the energy think tank Ember. According to EUPD methodology, which is later briefly referred to, the Chinese module import by the end of September is around 73.3 GW. [2] Obviously, this does not mean that Ember’s calculations are wrong, but to draw attention to the fact that there will be room for different results depending on more precise data and methodology. [3] Please note that in 2022, the EU-27 installed around 40.4 GW and Europe (including other big European markets such as UK, Turkey, Switzerland etc.) installed approximately 44 GW. [4] Please note that depending on the upcoming Q4-2023 data release the more precise estimation would be 57-60 GW for 2023. To find out more about how we collect and update our global PV data, please check EUPD Research’s Global Energy Transition Matrix on our website. [5] Please note that this is just an assumption made based on the Ember data export. As mentioned before based on EUPD methodology, the Chinese module export to the EU by the end of 2023 is estimated to be around 87 GW. [6] It should be noted that if the EUPD methodology for the 2022 Chinese modules export to the EU is taken, just like 2023, this export figures reduces. [7] Please refer to EUPD Research US Market Leadership Study released in September 2023. [8] Please refer to EUPD Research European Market Leadership Study released in 2023. [9] For more details please refer to SolarPower Europe website.About the authors: Markus A.W. Hoehner is the founder, president and chief executive officer of Hoehner Research & Consulting Group and EUPD Research. He has been active in top-level research and consulting, focusing on cleantech, renewable energy, and sustainable management for more than three decades.

Ali Arfa is the senior data manager at EUPD Research. With a background in politics and investor relations, he is leading several projects at EUPD Research. Among the most important is the Global Energy Transition Matrix online platform which constantly monitors the renewable energy and, especially, PV data of around 60 global markets.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

1 comment

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.