At the end of August, the Italian Council of State issued two different rulings. The institution is an important legal and administrative consultative body in Italy, with jurisdiction over the acts of all administrative authorities. With the two rulings, the Council of State effectively said that agrivoltaic projects cannot be treated as conventional ground-mounted PV plants.

“The two sentences outline a substantially different regulatory framework for agrivoltaics and traditional photovoltaics,” said Andrea Sticchi Damiani, a lawyer who was involved in the matter. “The administrative justice has filled the last gaps so the legislative framework for agrivoltaics is now completely clear.”

The two rulings relate to two projects in the Italian province of Brindisi, with generation capacities of 6 MW and 110 MW. The province is in the region of Apulia, which has one of the highest PV adoption levels in Italy.

“The criteria that were used previously, such as the consumption of territory with respect to normal agricultural use, is an objection that can no longer be raised,” Sticchi Damiani said. “They are not hectares taken away from agricultural areas. On the contrary, they are often formerly-unproductive areas that will become productive again.”

Italian ambition

REM Tec, an Italian agrivoltaic project developer with an international focus, describes itself as the first in the world to develop sustainable projects for solar energy production in the agricultural sector. The company’s French CEO, Ronald Knoche, says the primary hurdle for agrivoltaics in Italy is the lack of a clear definition of the technology.

France codified an agrivoltaic definition into law in March. While some details are missing, the definition specifies that land occupied by agrivoltaics should primarily be used for agricultural purposes.

Legal developments in Italy are slower even if commercial plans for agrivoltaics are more ambitious. In April 2021, the last Italian government, led by Mario Draghi until October last year, presented a €1.1 billion ($1.17 billion) plan to deploy a little over 1 GW of advanced agrivoltaic systems by June 2026. The installations must include “innovative” mounting solutions that place solar modules above the ground without compromising the continuity of agricultural operations.

“The Italian government has two approaches: a generic definition and a better way of doing it,” said REM Tec’s Knoche. “I don’t think it is the right way forward. Many stakeholders are accusing the local industry of doing ground-mounted agrivoltaic systems, ignoring the agriculture and landscape.”

He conceded that advanced agrivoltaic projects are expensive but suggested that the €1.1 billion fund is a way to support research activity seeking to establish best practice and avoid problems. Knoche mentioned Taiwan, which was a leader in agrivoltaic development before the Covid-19 pandemic. Concerning agrivoltaics, Knoche said, “It is now forbidden, as the industry was not doing projects very well.”

Follow the money

The REM Tec chief said the way to understand the power dynamic between agriculture and energy production is to follow the money.

Discussing the returns available from the two revenue streams, Knoche said, “A hectare will grant €100,000 for power production and as little as €2,000 for wheat agricultural production. This creates an imbalance, leading to some farmers receiving offers for land at €10,000 per hectare per year, from energy producers. It is an incentive to switch from agricultural production to power production: the income is higher and the risks are less. The Italian government seems to have partially understood it.”

Knoche said that agrivoltaics could account for the third-largest share of Italian PV power production in the future, behind traditional ground-mounted systems on industrial sites, and residential rooftop installations.

“Panel prices are decreasing, the knowledge about agrivoltaics is increasing, the economies of scale are such that the business models are changing, with agrivoltaics being one of the new business models,” he added.

The Joint Research Centre, the European Commission’s science and knowledge service, this year reported that agrivoltaic projects with 20 GW to 30 GW of generation capacity will have applied for administrative authorization under the national permitting process in Italy.

REM Tec worked with Italian standardization body UNI, national research agency ENEA, and the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore to draw up UNI/PdR 148:2023, a set of guidelines for the implementation of agrivoltaic projects.

The UNI standard, which incorporates existing regulations, has no practical application but proponents suggest it could facilitate permitting processes for local governments in Italy as well as administrative decisions for the country’s grid network authority, the GSE.

Land use

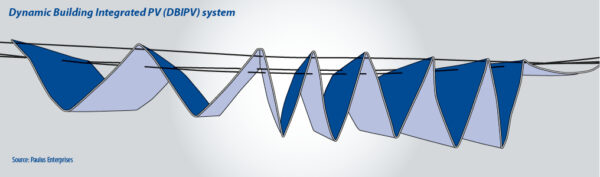

A Canadian inventor, Antoine Paulus, said new agrivoltaic designs are essential to decrease land usage. His own invention, dynamic building-integrated PV (DBIPV), is a mobile and removable system based on existing technology.

“My concept is based on shades with PV panels inserted in them, strung over the land with steel cables from mobile platforms at a higher elevation, to allow farm machines and livestock to pass under without obstruction,” explained Paulus. “With mobile platforms at the two ends, it is possible to stretch the shades over any area and close and move them or relocate them.”

DBIPV makes use of thin, light, and flexible PV panels, such as fiberglass-based silicon PV or organic modules. The steel cables are similar to those used in cranes. Paulus said his concept is safe as the units can be folded quickly in the event of an emergency.

“The fact that they are used in smaller clusters and each panel is in a sleeve separate from the other is another advantage,” Paulus added.

The Canadian inventor said that because the concept has not been tested yet, it is difficult to provide a levelized cost of energy estimate. Paulus said the utility of his invention is a no-brainer as it makes perfect commercial sense.

Alessandra Scognamiglio, coordinator of a task force on sustainable agrivoltaics at ENEA, said that similar, integrated projects have been considered before in the field of building-integrated photovoltaics but were not successful simply because of the effort required to create demand for them. “The market is generally not ready for innovation,” she said.

Apart from collaborating on the UNI standard, ENEA continues to research agrivoltaic projects. By the end of the year, it aims to release an online map that will assist with the selection of appropriate locations, based on factors that can positively affect co-located agricultural and energy production projects. Scognamiglio said the map would not include areas with restrictions on land use for PV.

The researcher, who also serves as president of sustainable agrivoltaic association AIAS, added that Italian authorities have so far placed little value on carrying out research activity on agrivoltaics, instead preferring to invest European Union funds in single projects.

“Private entrepreneurs are doing the research themselves, through universities and other entities,” said Scognamiglio. “The UNI standard is part of this context, a context where a clear regulatory framework is lacking.”

In June 2022, the Draghi government published guidelines for agrivoltaic projects but since the relevant minister did not sign them, they still do not actually have a legal basis.

“In October 2022, the government said it would make the necessary changes to the guidelines after discussions with operators,” explained Scognamiglio. “This has not happened.”

Legal position

Addressing Sticchi Damiani’s claim the legislative framework for agrivoltaics is now completely clear, Scognamiglio said that the lawyer is correct from a legal perspective.

“Any plaintiff who goes to court is now expected to win. This is not to say that a cultural gap has been filled because the word ‘agrivoltaic' is new, and it has not yet been defined,” she added.

That process is likely to lead to lawsuits or disjointed legal development. Scognamiglio warned that Italian regions have already started writing their own local guidelines on agrivoltaic installations in response to the number of requests they have received, and the scale of some of the projects. The Piedmont region, in northern Italy, published a principle for agrivoltaic projects in farming lands with high agronomic interest. The so-called “principle of continuity” requires agricultural production in the three years following the agrivoltaic installation to be at least 70% of the value of the farm output in the five productive years before deployment.

Shortly after Piedmont published its guidelines, the Italian government released a draft decree on “eligible areas,” a requirement of the soon-to-be-passed European renewables directive Red III. Scognamiglio confirmed that the constraints of the Italian draft decree would apply to some agrivoltaic projects: those on the ground, and inter-row PV systems. “It is most probably because agrivoltaics are still not credible enough to agricultural stakeholders, as the real difference between agri-PV and ground-mounted PV is not defined,” she said.

Industry pushback

Trade association Italia Solare says that the PV sector is being called on to achieve stringent renewables capacity targets. It believes that a preference for elevated systems would be detrimental to efforts to achieve these targets, as only 1 GW of annual installations, with high costs, could be achieved in the country with this technology. It notes that such arrays would also have a significant impact on the Italian landscape.

Rolando Roberto, vice president of Italia Solare, has argued constraints that include a preference for elevated systems could be viewed as counter-productive.

“Steel is no innovation,” he said. “Elevated systems with fixed maximal height sometimes do not make sense. Ministerial guidelines and other regulatory guidance documents qualify systems with minimum heights of 2.1 meters and 1.3 meters for agricultural crops and livestock activities, respectively.”

The PV association also said the sector must work on agricultural productivity data, analyzing different crops and climates. “Only when data are available can percentage constraints be introduced,” it explained. “Agrivoltaics must gain experience through experimentation, research, and development. In the meantime, however, it is necessary to allow the installation of efficient and truly achievable systems, in addition to experimental plants, even without the support of European subsidies.”

Perspective of farmers

At the other end of the debate, farming unions are asking for more restrictions on agrivoltaics. Coldiretti wants its members to be driving agrivoltaic deployment as, it argues, they will prioritize continuing food production on such sites.

“The integration of energy production in agricultural activities should not upset those balances that qualify agricultural income,” said Stefano Masini, environment and land manager at Coldiretti. “The sizing of installations should not depend on economies of scale or industrial logic, as is the case with ground-mounted photovoltaics.”

Masini argued that investments in agrivoltaic projects could be seen as a loophole to incentivize ground-mounted PV on agricultural soil. “According to data from the 2014 GSE statistical report, the area of panels installed on the ground at that date amounted to 13,877 hectares, of which 4,000 were in Puglia alone,” he said.

He said the total land requirements of ground-mounted solar projects meant that figure translated into around 30,000 to 35,000 hectares removed from agricultural use.

Scale

“The actual figure, however, is semi-unknown since, especially in recent years, there has been a sharp increase in incentive-free large-scale PV investment,” added Masini

The Coldiretti rep said that if utility scale projects were predominantly found on agricultural land, an additional 70,000 to 90,000 hectares could be taken away from agricultural use, equal to about 0.3% to 0.5% of current agricultural land.

Masini said he favors tailor-made installations that could increase farmer competitiveness but he cautions that there are significant complexities. Funds, which in some cases come from European Union programs, often have an expiration date.

“The need to make agrivoltaics a technology that can easily and quickly access energy incentives probably does not fit well with the complexity that requires an approach of real integration between energy and [agriculture],” he said.

Agrivoltaic expansion could also inflate land rental values, said Coldiretti, which claimed rental prices could rise by 40%. “The average bid for land for photovoltaic or agrivoltaic fields is four to five times higher than the normal market value. But, in some cases, it is as high as 10 to 15 times. It depends on the location of the land.”

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

2 comments

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.