Every country has its energy guru and France is no exception. Jean-Marc Jancovici – through books, conferences, and now a comic – is the definitive voice of his nation’s nuclear industry.

I have always enjoyed listening to Jancovici’s keynote speeches. He has a remarkable talent for storytelling. He can explain the most complex physical concepts and even make them funny. Where we differ is on the relevance of renewable energy for reducing carbon emissions, and the primacy of nuclear energy over all other power sources.

As we are of the same generation, I know the emergence of nuclear technology in the 1970s sparked fascination for many young talents with a passion for science. If I had not been born into a family of electronic engineers – pioneers of telematics – I too could have chosen to join “those who want to control the atom.”

It was at that time that France instituted a major industrial turnaround that would see the construction of 58 nuclear reactors in 29 years – four presidential terms.

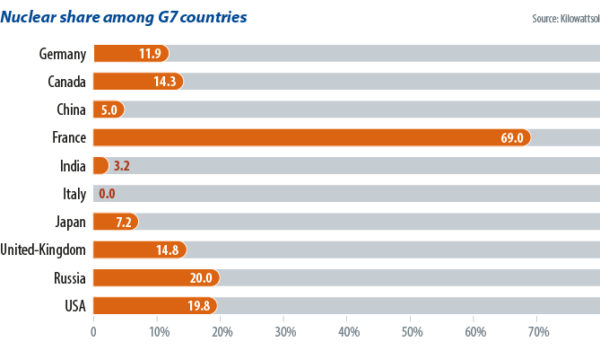

With 70% of the French electricity mix comprised of nuclear power plants, my country is today a singularity in the energy landscape of sovereign states, to say the least. Nowhere else in the world does nuclear make up more than 20% of the power mix.

French exceptionalism is a speciality anchored in our national DNA. But it turns out, as Jancovici has stressed repeatedly, physics are also quite stubborn. We are talking about an energy source that is by nature predestined to produce the baseload of daily electricity demand, and one does not need to be a brilliant engineer to understand that speaking of a “baseload,” when nuclear is close to 70%, is perhaps going a bit too far.

Nuclear fleets are generally regarded as non-dispatchable, even though some reactors can perform load-following operation. Our literature shows such adjustments of energy output are always devoted to specific reactors, never the full French fleet, even in cases of extreme excess-energy waste. As this is a recurrent topic on social networks, though, I would be interested in a fuller explanation of the dispatchability or otherwise of nuclear. Grid flexibility instead typically focuses on “peaker” energy sources, mainly thermal and hydroelectric power plants.

As a result, France has found itself with an electricity surplus since the late 1980s that it has had to learn to absorb. Our country has incredible talents, however, and we developed energy storage – as much as it is possible to “store” electricity – by increasing the capacity of our hydro pumping stations by 84% through the invention of “off-peak hours” to direct consumer demand, and by deploying more than 11 million heaters to store night-time surpluses in the form of domestic hot water.

Not just nuclear

Those who advocate nuclear power as the sole electricity source likely to offer our planet a carbon-free energy mix are doubly mistaken, because the technology does not meet the challenges of magnitude or speed of deployment. The power of the atom is only suitable for a very limited number of countries for technological, infrastructural, and safety reasons. Moreover, the speed of nuclear power plant construction is not compatible with the timeframe imposed by our climate crisis.

Even if it surpasses all other energy sources in terms of the density of its production units – a nuclear power plant can accommodate more than 5 GW of power generation capacity per square kilometer – the complexity of each reactor project makes them increasingly long to develop and build. That requires thinking on a scale of 20 to 30 years, as opposed to just a few years for renewable energy projects. The speed of reactor construction is particularly slow compared to photovoltaic energy sites, whose installation period is ultimately a reflection of the level of permitting complexity desired by legislators.

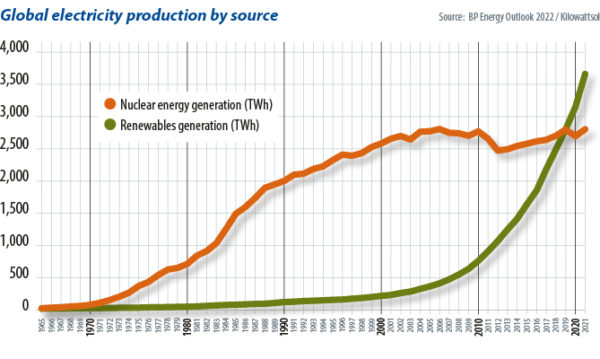

Added to those two failings is a fear of nuclear energy that has always animated some people, and which has been amplified following the Chernobyl and Fukushima incidents. Such concerns are reflected by the development curve of global nuclear power generation. Even at the height of its accelerated deployment, the world never saw more than 17% of nuclear generation capacity added than had already been installed, and nuclear came close to that rollout rate for only five years – thanks to French enthusiasm in the 1980s. Today, nuclear generation capacity has reached a ceiling of 2.8 PWh per year, whereas wind and solar energy sites, notwithstanding their intermittency, have been growing continuously at a rate of more than 17% per year since 2010 and surpassed nuclear in 2019, to jointly produce more than 4 PWh today.

Energy mix

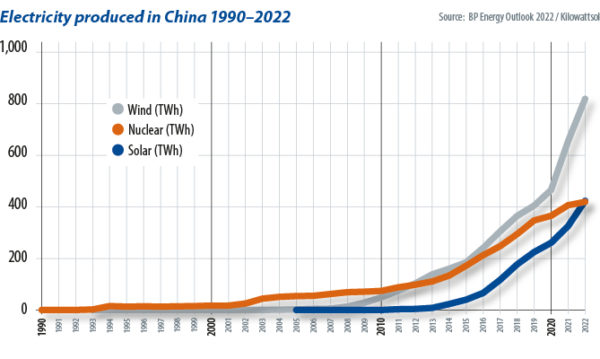

China, a country with a robust energy infrastructure which includes a substantial nuclear fleet, has understood this well. Starting from a blank slate for nuclear, wind, and solar, it began implementation of the former in the 1990s, then wind power in the early 2000s, followed by solar power around five years later. The production curve for wind power doubled that of nuclear from 2010 onwards and solar caught up at the end of last year. China is on its way to becoming the dominant industrial player for these three sources of electricity.

When the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases makes a commitment to the United Nations, through the voice of its leader, to reach peak CO2 emissions before 2030, and to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060, it does so based on sound planning that favors the combined effect of two renewable energy sources – wind and solar – rather than relying solely on nuclear.

This ambition should alert the world to the strategic value of solar and wind energy and the commercial potential they already represent on a global basis. Countries all over the world are adopting these energy sources on a massive scale, including through ambitious industrial reinvestment programs.

French complexity

The French parliament has just approved a heavily revised version of a new bill related to acceleration of the production of renewable energy. The bill is a text that adds more constraints than it takes away from one of the most complex legislative systems in Europe and which, until now, has failed to out-perform any of its neighbors in rolling out clean power. The concerns expressed by both senators and MPs, and transcribed into as many additional conditions as possible, are being interpreted by the renewables industry as “no,” “go elsewhere,” and “not here.”

The country which displays the strongest ambition regarding renewables will be considered the most attractive by manufacturers of clean power technology and investors in such businesses. The existence of a domestic market is a prerequisite for any entrepreneurial clean power initiative.

What place will France claim for the technology that may be the key to tomorrow’s energy model? Will legislators enable the emergence of a French, or European, offer that will embrace youth, research, and the industry for the next two decades?

Focusing exclusively on a single electricity source is a risk because, whatever France decides, the 21st century will be the age of renewable energy. By fine-tuning the law by issuing the necessary decree, the industry must solemnly appeal to the French government and energy minister Agnès Pannier-Runacher: “Be bold.”

About the author: Xavier Daval is the founder and CEO of KiloWattsol, a solar technical consultancy. He is also the vice president of Syndicat des Énergies Renouvelables, where he chairs the solar commission, and serves as the co-chairman of the Global Solar Council.

About the author: Xavier Daval is the founder and CEO of KiloWattsol, a solar technical consultancy. He is also the vice president of Syndicat des Énergies Renouvelables, where he chairs the solar commission, and serves as the co-chairman of the Global Solar Council.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.