From pv magazine 04/2022

Investors are in a difficult position. On the one hand, there is the need to tackle on-time delivery as well as commercial aspects with priority. On the other, PV plants are expected to operate in the meantime for up to 40 years, in order to further reduce levelized costs of electricity (LCOE). Long-term reliability is therefore a pre-condition and given the current situation, more difficult to achieve.

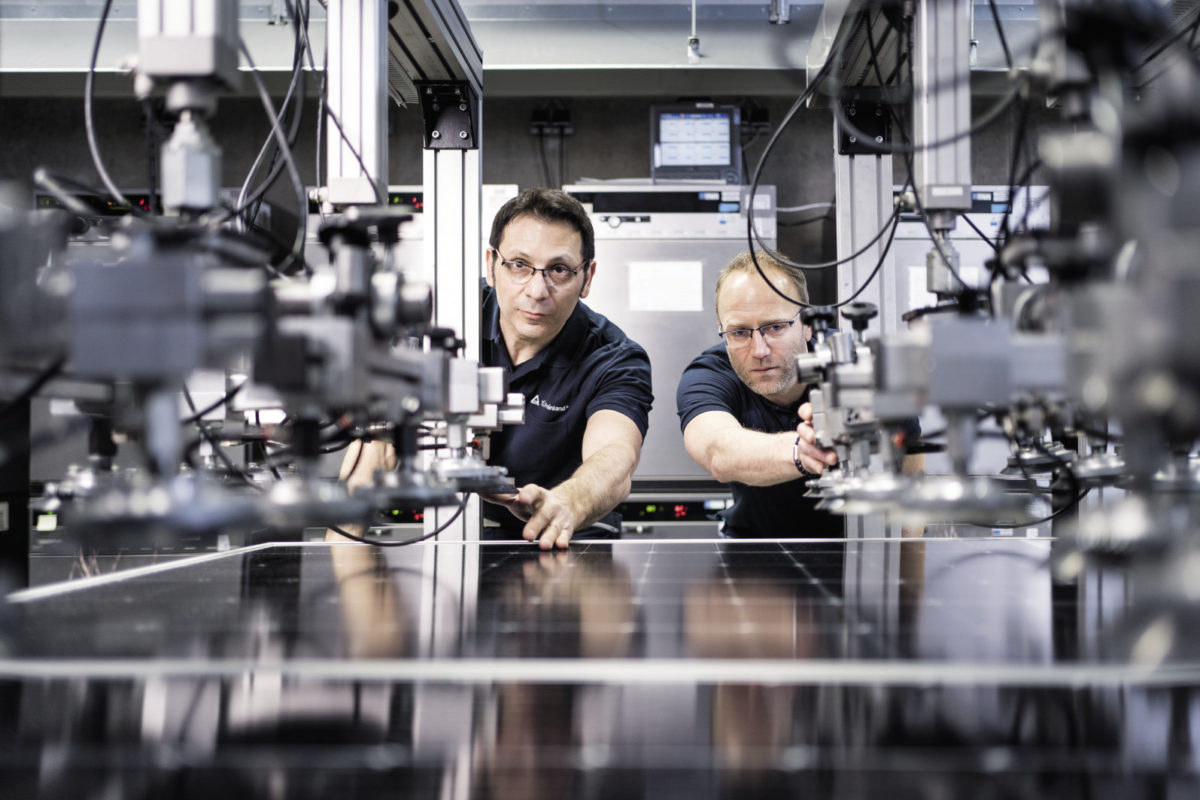

On the LCOE side, manufacturers have reacted by increasing PV cell and module sizes. This not only reduces the cost of PV modules per watt, but helps to positively impact balance-of-system (BOS) costs. However, tests in TÜV Rheinland’s laboratories have shown that those modules are failing in mechanical stress tests more often when compared to smaller-size modules. Especially in areas with high wind and snow loads, this could cause issues in both performance and safety. Smaller distances between cells increase thermo-mechanical stress, which can lead to cell cracks and corresponding hot spots. Also, higher string power may result in hot spots in a reverse bias situation, as well as failures of bypass diodes. The new dimensions of PV modules challenge solar laboratories as well; in particular, old solar simulators may not be able to reach the required uniformity of irradiance, compromising measurement certainty. There is at least one positive side effect, however: The typical failure mode of “scratches in the backsheet from helmets” does not exist anymore.

Forty-year modules

For an operating time of 40 years, long-term reliability risks are evident, and for investors, stringent quality tests are absolutely necessary. Typical test programs for PV module qualifications, such as IEC 61215 and IEC 61730, are not considered sufficient to cover safety and performance aspects after a few years of operation. Extended stress testing in accordance with IEC TS 63209-1 is a good basis. However, once the testing procedure is passed, it can at least be asked what that means for a specific photovoltaic power plant project.

Changing critical components of a PV module, due to price or availability or any other reason, immediately compromises the value of the “pass result.” In an attempt to solve this issue, TÜV Rheinland has created the “Quality Controlled PV” standard 2PfG 2715. In addition to IEC TS 63209-1, a well-defined retesting guideline for design and material modification is in place, which allows sufficient flexibility for manufacturers by keeping confidence of investors. The Extended Stress Test (Part 1) is supplemented by Regular Monitoring (Part 2) and Monitoring of Suppliers and Materials (Part 3).

PAN files

For investors, it is essential to predict future yields of an asset precisely. The industry has mostly understood that climate data – or the typical meteorological year (TMY) – are key for a meaningful assessment, and that related data are a must-have, at least when it comes to project financing. Surprisingly, investors often underestimate the influence of equipment-related parameters. PAN files are the file types in the solar simulation software PVsyst, in which PV module-related parameters are stored. PVsyst provides a huge amount of PAN files, covering nearly all commercially available PV module types. Respective parameters are usually extracted from manufacturer datasheets and do not reflect the variety of possible bill of materials (BOM). Therefore, those standard PAN files can only be considered as approximation to real behavior. It is highly suggested to use a PAN file which has been created by an accredited party and which is typically provided via the manufacturer. It is important to verify the respective test report to identify possible deviations in the tested from the project BOM. This validation is possible via a simplified test scheme. Ideally, a project-specific PAN file from PV modules out of the production line is created, which enhances trust and reduces uncertainties in the solar yield prediction.

Even though the situation in the solar supply chain will remain tense throughout most of 2022, there is light at the end of the tunnel. India and Europe are investing massively in new manufacturing lines for solar equipment, solving trade related issues and logistical challenges. Nevertheless, for now it is not yet clear what this means for quality and long-term reliability, and if this will contribute to lower LCOE going forward.

About the author

Sebastian Petretschek is TÜV Rheinland’s global head of PV power plants, based in Shanghai, China. He has been active in the renewable energy business since 2009. For C&I and large-scale PV power plant projects, he has supported lenders, investors, EPC companies and other parties in the development, construction, commissioning and operation of assets on six continents. He is also a quality assurance specialist for the value chain of PV components.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

9 comments

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.