“Energy security now has a different level of significance and priority… renewable energy not only contributes to energy security and energy supplies, but it also frees us from dependence. Renewable energy is the energy of freedom,” Lindner said.

But as the drive for increased capacity in solar energy takes on new urgency, the sector risks being perceived not as ‘the energy of freedom’, but rather as a driver of forced labor.

Our new research report, ‘The Energy of Freedom’? Solar energy, modern slavery and the Just Transition, seeks practical solutions. We set out a new method of estimating the risk of forced labor in the on-grid PV production system of individual countries, and propose a roadmap for international collaboration to address those risks.

We also address risks of supply-chain fragmentation arising from emerging regulatory requirements relating to forced labor risks. These include the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act in the US and the EU’s consideration of a forced labor legal instrument.

Given the global nature of the value chain, single-country and single-region solutions risk producing fragmentation. The problem is that this may raise costs and roll-out times, and reduce innovation, without necessarily addressing existing forced labor risks.

As we explore in the report, the solution to supply-chain bifurcation is collective action to transform the value chain so that forced labor risks are minimized in the first place. This is likely to involve industry stakeholders working together to develop a global ‘roadmap’ for both remediation of existing forced labor risks and development of new, forced-labor-free production capacity.

Risks

Industry players will be familiar with the issues. Around 40% of the global supply of polysilicon comes from Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, where some of it is suspected of being made with state-sponsored forced labor. And between 15 and 30% of the cobalt in lithium-ion batteries used to store solar energy comes from informal mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Forced and child labor are common. Forced labor risks can also arise in other contexts.

The presence of forced labor in these supply chains poses growing risks not only to workers but also to importers and investors.

The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, passed in the United States in December 2021, will prevent the import of goods made with Uyghur forced labor from June 2022. Already, US Customs and Border Protection has detained millions of dollars of PV products under the Tariff Act of 1930.

The European Commission is also preparing a new legal instrument to ban the sale of goods made with forced labor in the European single market.

Solar energy stakeholders have called for more clarity on how value chains will deal with these risks. Markets are looking for clarity on how manufacturers will undertake effective supply chain due diligence and remediation.

Investors are looking for buyers to set out transparent timelines for disengagement from suppliers tainted by forced labor. Some development finance institutions and multilateral development banks have begun working to develop common approaches to these risks, which will see them stop financing projects and withdraw from relationships that exceed defined forced labor risk thresholds, or where suppliers or clients fail to take required remedial actions within defined periods.

But some of these changes are having unintended consequences.

Our newly published, peer-reviewed research from the University of Nottingham’s Rights Lab – funded by the British Academy, one of the UK’s leading research funding bodies – reports that a new focus on ‘re-shoring’ PV supply-chains risks splitting the global market. One set of supply chains may provide ‘forced labor-free' solar products to clients who want them, while another set provides forced labor-made goods to other clients. That split may not only do little to help people forced to labor to make polysilicon and mine cobalt but could also raise costs, reduce innovation, and slow decarbonization.

So what practical solutions are available to the industry to address these risks, and how can our research help?

A new approach to estimating risks

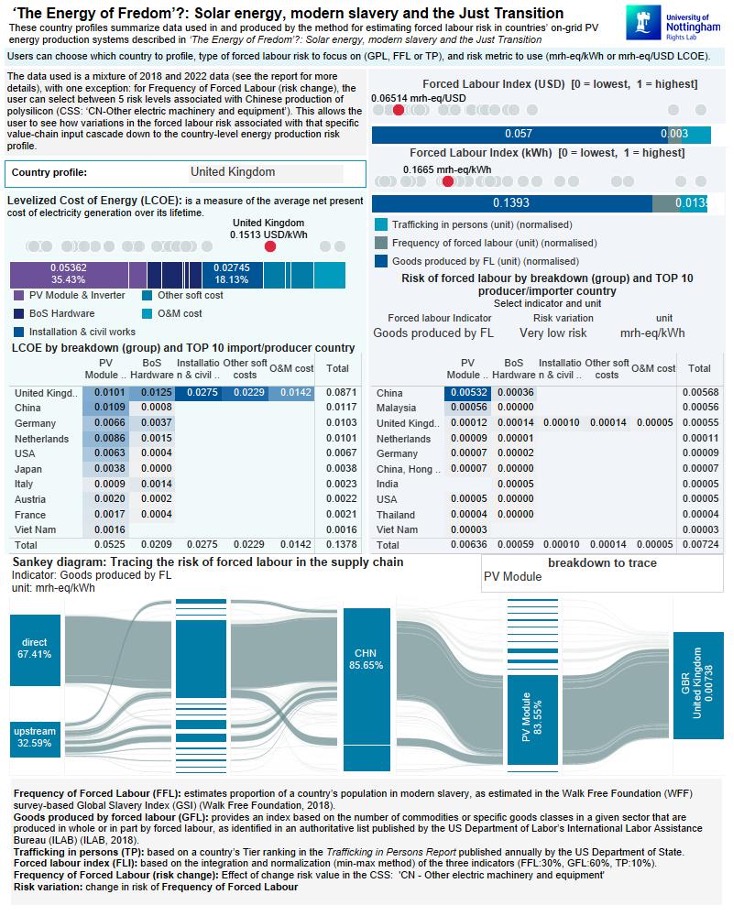

Our report sets out a new way of estimating the forced labor risk in the on-grid PV energy a country produces, accounting for all the forced labor risks earlier in the value chain. These risks can be calculated per kWh or per USD LCOE.

The method uses export-import data, the latest available PV lifecycle and LCOE information, and data on the risk involved in producing the different inputs into the PV energy production system. It provides detailed insights into the nature, size, and source of forced labor risks in country-level PV, and on-grid production systems. The data comes from a combination of sources: the UN (UN COMTRADE), the International Renewable Energy Agency, World Bank, and PSILCA, which provides forced labor risk metrics that draw on the US Department of State, US Department of Labor, and Global Slavery Index data.

The purpose of this new method is not to rank countries, but rather to provide a method for identifying how and where forced labor risk arises in the different inputs that feed into PV energy production. These risks cascade down the value chain affecting subsequent buyers and end-users. The method also allows tracing of how changes in the forced labor risk associated with specific inputs, such as polysilicon or cobalt from specific sources, cascade through the value chain to different buyers and production systems. This allows users to connect procurement, investment, and planning decisions to defined risk parameters.

Our findings apply the method to national-level data. The best such available data comes from 2018 and 2022. We provide interactive country profile visualizations which allow the user to control risk settings for ‘frequency of forced labor’, giving them the ability to see how different perceptions of risk cascade through the value chain. We provide these for the top 30 on-grid PV-producing countries.

The analysis applies only to embodied risk. We do not seek to assess how companies are responding to or mitigating these risks. With the right input data, however, the method could be adapted to firm-level inventories, allowing inter-firm and project-level comparison, which may prove useful for developers and investors.

A global roadmap to provide certainty and reduce risk

Our report argues that a global roadmap for transitioning the industry to a forced labor-free footing is urgently needed. Manufacturers and developers, buyers, investors, governments, and civil society should come together to address forced labor risks by acting along the value chain.

Stakeholders should agree on plans, incentives, and timelines to move the industry towards a model that addresses the social externalities generated by solar energy production, storage, and use. These incentives could include sustainability-linked finance, market access, or tax credits.

Investors and lenders may have an important ‘stewardship’ role to play in driving change across the PV ecosystem. They could work together with developers, manufacturers, and major buyers to agree to transitional arrangements for the path towards zero forced labor risk in solar energy value chains. Transitional arrangements could accelerate progress by linking product and capital costs to forced labor risk metrics.

Industry associations also have a key role to play. But if they do not step up to develop such a roadmap, government-based forums in which such a discussion might be convened include the International Solar Alliance, the OECD, and the US-EU Trade and Technology Council.

Such an approach would create greater certainty for developers, investors, and consumers, and help create efficiency by allocating costs to those that are the highest sources of risk in the system. In the current arrangement, firms that tolerate forced labor are allowed to undercut those who respect human rights.

A transitional roadmap will be critical to ensure the solar industry is indeed regarded in future not as a source of forced labor risk, but as ‘the energy of freedom’. It is time to act.

‘The Energy of Freedom’? Solar energy, modern slavery and the Just Transition is by Prof. James Cockayne, Dr Edgar Rodríguez Huerta and Dr Oana Burcu and is available online.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

It’s ridiculous. Local people in Xingjiang find a job in a pv company .They pay their labor, company pay workers salary. Why some people think it’s forced labor? Any evidence to show that?

If that counts as forced labor, then there should be forced labor in The Motor city of Detroit. People should not buy USA vehicles.