One of the main reasons for substantial capacity losses and even fires in lithium batteries are little islands of inactive lithium that are created during the nonuniform dissolution of lithium dendrites. This isolated lithium loses connection with the current collector, so it is considered electrochemically inactive or “dead,” but a team of US researchers has discovered that this lithium can be brought back to life, boosting the capacity and lifespan of batteries.

Researchers at the US Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University have shown that isolated lithium is alive and highly responsive to battery operations, due to its dynamic polarization to the electric field in the electrolyte. They have designed an optical cell with a lithium-nickel-manganese-cobalt-oxide (NMC) cathode and a lithium anode. They also used an isolated lithium island in between as a test device that allowed them to track what happens inside a battery when in use, in real time.

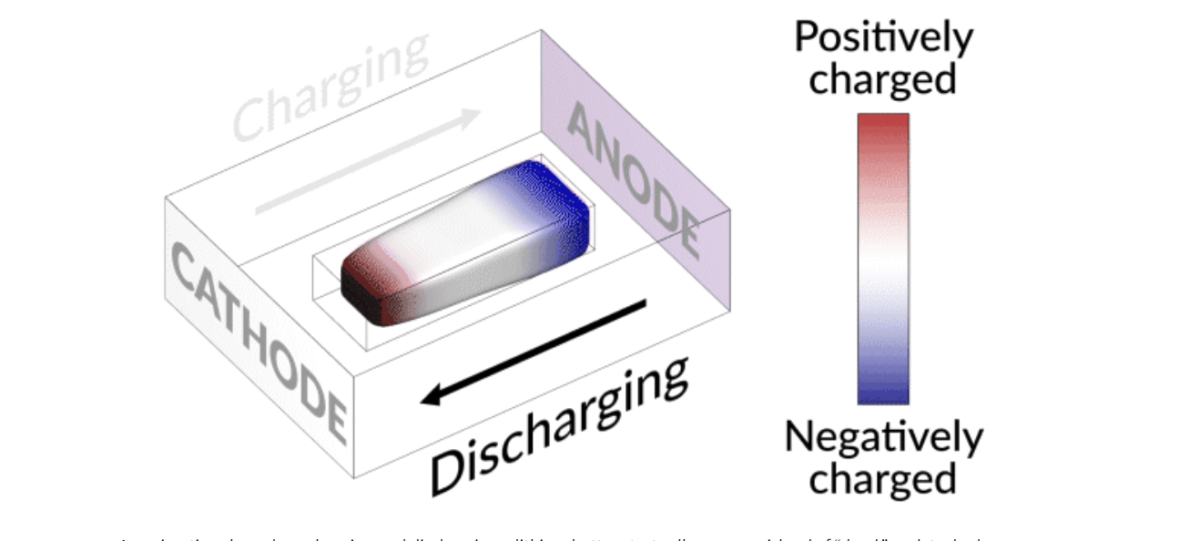

They discovered that when charging the cell, the island slowly moved toward the cathode. When discharging, it crept in the opposite direction.

“It’s like a very slow worm that inches its head forward and pulls its tail in to move nanometer by nanometer,” said Yi Cui, a professor at Stanford University and SLAC, and an investigator at the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Research. “In this case, it transports by dissolving away on one end and depositing material to the other end. If we can keep the lithium worm moving, it will eventually touch the anode and reestablish the electrical connection.”

Lithium metal accumulates at the negative end of the island and dissolves at the positive end. This continual growth and dissolution causes the back-and-forth movement that the researchers observed. Their next step was to modify the charging protocol in order to move these floating islands far enough to reconnect with the anode.

They discovered that by adding a brief, high-current discharging step right after charging, the battery nudges the island to grow in the direction of the anode. As a result, the researchers demonstrated that they can mobilize and recover the isolated lithium, extending the battery’s lifespan by nearly 30%.

The researchers expect these findings to have broad implications for the design and development of more robust lithium-metal batteries. Their study, “Dynamic spatial progression of isolated lithium during battery operations,” was recently published in Nature.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.