“PV power output is directly driven by meteorological conditions, and its drivers are likely to change in the future.” This statement, a few pages into a new paper by researchers at the University of New South Wales, seems obvious. But its implications as temperatures rise and weather patterns alter due to climate change will inform our expectations of solar output to 2079 and beyond.

The conclusions reached by the paper, “Estimations of future changes in photovoltaic potential in Australia due to climate change,” provide insights into where solar farms could best be located as this century progresses. It is the first study to use high-resolution regional climate projections in Australia to forecast changes in PV potential due to variations in shortwave downwelling radiation, temperature and wind speed; and the first ever to consider the additional impact of changes in cell temperatures.

Shukla Poddar, a doctoral student at the UNSW School of Photovoltaic Energy and Engineering (SPREE) and lead author on the paper, told pv magazine Australia that the most surprising outcome of this research “is the cell temperature effect.” In other words, it’s obvious that changes in irradiation might cause increases or decreases in solar PV output in the decades-distant future, but in fact, ever-increasing ambient temperatures implicit in global warming will also reduce cell efficiency and will likely accelerate the degradation of solar cell.

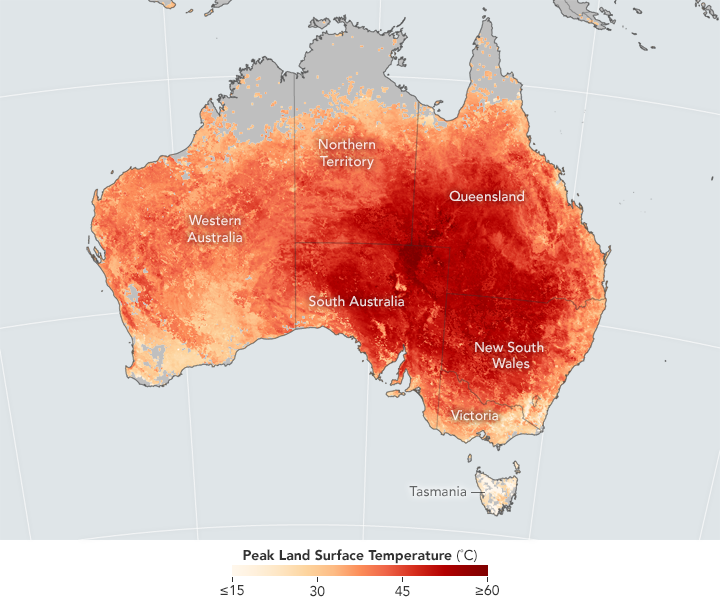

As UNSW Scientia Professor Martin Green has famously said, “Solar cells would prefer to be operating in a fridge.” Instead, their operating environment is typically hot, and becoming relentlessly hotter. Poddar and co-authors have measured the effect on polysilicon solar cells of temperature rises under a high emissions scenario that projects warming of 3 C to 4 C by 2100.

It’s not that the researchers are pessimists – far from it. But high-resolution climate simulations available from the New South Wales/Australian Capital Territory Regional Climate Modelling (NARCliM) project used the high-emissions A2 scenario, and the previous study into wind resource by one of Poddar’s co-authors, Jason Evans had also used the NARCliM data. Using the same data, ensures the two studies are relatable, to give an overall picture of how Australia’s renewable resources will fare under climate change.

“When you’re thinking about this work, it serves as a risk management strategy,” a third co-author, Dr Merlinde Kay, told pv magazine Australia. “It describes what could happen in the future and gives people enough time to prepare for what the most extreme outcome could be.”

To continue reading, please visit our pv magazine Australia website.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.