From pv magazine 09/2021

The Biden administration has big plans for fighting climate change in the United States, including aggressive infrastructure aims. Solar will play a big part in the new agenda, and participants along the value chain are optimistic.

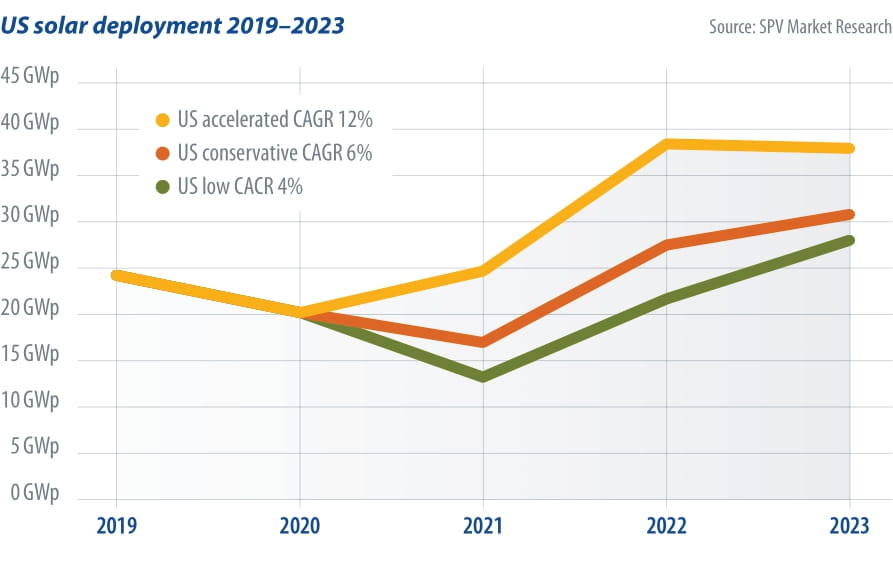

Developers are gearing up. Residential and small commercial installers are confident. In California, mandates for solar on new residential buildings – and soon for solar+storage on new commercial and multi-dwelling residential buildings – offer a template for accelerating the move away from conventional energy. The chart below provides a view of U.S. solar deployment through 2023, but the real potential is much higher. The United States could be a 50 GW-plus annual

market for solar deployment.

In 2020, 91% of U.S. installations were in the grid-connected commercial segment, which includes utility-scale installations. The top-right chart on the next page presents U.S. demand and installations for 2020. Purchases of modules define demand.

Import country

The United States has more than 20 GWp of annual demand, 2 GWp of thin-film cell capacity, and an additional 5 GWp of module assembly capacity for imported crystalline-silicon (c-Si) cells. In other words, the country does not have the capacity to serve its market. The U.S. solar market is fragile without sufficient domestic cell manufacturing, and participants have little control over module supply and price. A shock to the supply chain would likely stall market growth, at least temporarily, potentially taking that 50 GWp-plus of potential down to the low teens.

The bottom-left chart on this page presents U.S. shipments of domestically manufactured cells from 2010 through 2020. Again, close to 100% of U.S. domestic shipments are First Solar’s CdTe technology.

System shocks

In late 2020, accidents in several polysilicon facilities in China took significant amounts of capacity offline. And repairs were delayed due to the pandemic. Add to that the Chinese government’s control of glass supply, despite bifacial module demand acceleration, and prices rose.

Continuing into 2021, shipping costs increased, and a semiconductor shortage affected inverter and tracker manufacturers that were also experiencing rising costs, after years of absorbing margins and passing higher costs to customers. Developers, accustomed to years of price declines, initially tried to wait it out.

Meanwhile, the situation in the Uyghur Autonomous Region of Xinjiang, China, caught the attention of politicians. In anticipation of action from the United States and other countries, China’s central government passed a law on June 10 forbidding Chinese companies from participating in audits of their materials.

Then, on June 24, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security ordered U.S. Customs and Border Protection to issue a withhold release order (WRO) to detain metallurgical silicon produced by Hoshine Silicon Industry Co., Ltd., and its subsidiaries for the use of forced labor in its manufacturing facilities. Hoshine Silicon is the largest metallurgical silicon supplier globally. Its customers are polysilicon producers such as Germany-based Wacker, South Korea-based OCI, Daqo, GCL, Jiangsu Zhongneng, Asia Silicon, Xinjiang GCL, Xinte, and East Hope.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection has begun holding cells and modules at the border, delaying projects, and increasing costs and anxiety for solar developers and installers.

Ethical dilemma

The United States faces a moral and ethical dilemma. On one hand, after years of discussions and delayed action on climate change, governments must act decisively and quickly. On the other hand, forced labor cannot be ignored.

The English philosopher Philippa Foot developed the “trolley problem” in 1967. An out-of-control trolley car is barreling down the tracks toward five trapped people. There is no way to stop the trolley, but if you throw a switch, the trolley will instead barrel down a track where only one person is trapped. So, the choice is five or one.

There is no bargaining with climate change. Unaddressed, it will keep barreling down the tracks. But nor is there any compromising with forced labor or other troubling measures. Nor is there any denying that forced labor may have played a part in the low cell, module, and system prices that the PV industry has enjoyed for many years.

The political timing is right for U.S. solar industry growth to accelerate beyond anyone’s forecast. Behavior has changed, and there is pull from end users. Solar has moved into the political arena, with proponents on the left and the right.

Unfortunately, as indicated, the United States does not have sufficient cell manufacturing to meet its demand, and it will take years to build it. There is sufficient supply unrelated to forced labor in Xinjiang for the United States, but it will be more expensive, and there will be periods of scarcity. Growth will come at a higher cost – but not a higher moral cost. Because, again, there is no compromising with forced labor.

Paula Mints

About the author

Paula Mints is the founder and chief analyst of SPV Market Research. She began her career in 1997 with Strategies Unlimited. In 2005 she joined Navigant, where she served as director of its energy practice until October 2012, when she founded SPV Market Research, a global PV market research firm. Her areas of expertise include global markets, trends, solar product applications, cell and module costs, and system analysis – including inverters, trackers, and other balance-of-system components.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.