From pv magazine 08/2021

Battery electric vehicles (EVs) will be the dominant form of road transport by 2050, accounting for 56% of all vehicle sales that year. Our research indicates that in 2050, we will see 875 million electric passenger vehicles, 70 million electric commercial vehicles, and 5 million fuel cell vehicles on the roads. This brings the grand total of zero-emissions vehicles in operation to 950 million by mid-century.

Additionally, more than three out of every five vehicles will be EVs in China, Europe, and the U.S. by 2050. And almost one in two commercial vehicles will be electric by the same date in those regions.

The projected growth in EV sales spells bad news for internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles. Sales of ICE vehicles, including micro/mild hybrids, will fall to under 20% of all global sales by 2050. Almost half of the remaining ICE stock will reside in Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, Russia and the Caspian region, despite those markets only possessing a combined 18% of global vehicle stock that year.

Driving electrification

Policies of net-zero are transforming the global landscape. Transport is one of the largest contributors to emissions, as well as one of the lowest-hanging fruits. Countries accounting for more than 50% of global car sales and automakers representing 80% of global sales have expressed a desire to be carbon neutral, and many have laid out concrete plans to do so.

With new supply chains and new dependencies, traditional OEMs are innovating with their business models. The stage seems set for an overhaul of road transport, but with OEMs making frequent, flashy EV announcements, the question of how, when, where, and who is subject to debate.

Leading the charge

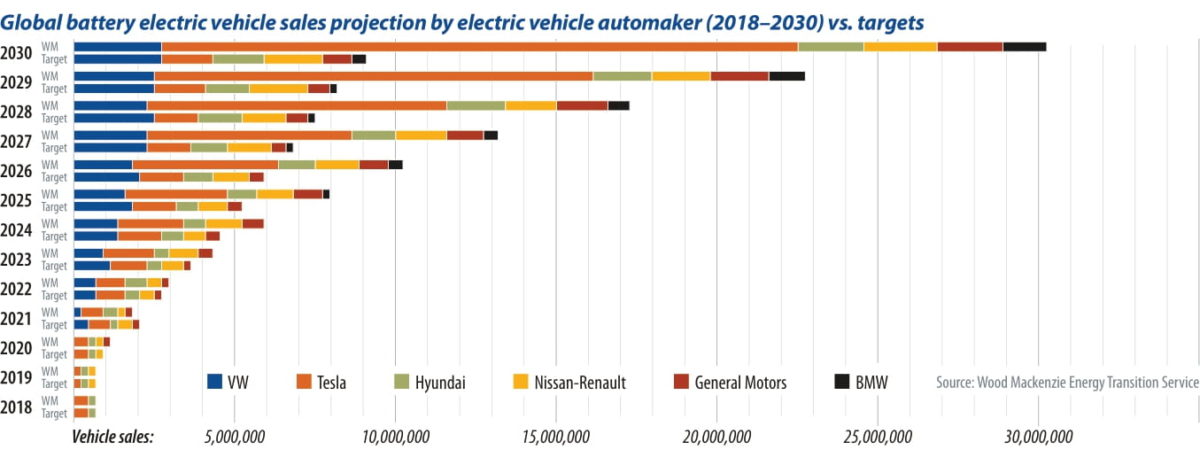

The top five Wood Mackenzie projected EV automakers – Tesla, Volkswagen, General Motors, Nissan-Renault, and Hyundai – have committed to a combined 8.9 million in annual sales of battery EVs by 2030, or nearly 50% of our projected global battery EV sales. The companies will hit 39% of their target by this date, with Tesla’s ambition of 20 million annual sales by 2030 heavily skewing the success rate. Without Tesla, the other four automakers would hit 79% of their 2030 target sales.

Even though Tesla is currently ahead, with just over half a million electric vehicle models sold in 2020, competition from OEMs, and particularly Volkswagen, is heating up.

According to Wood Mackenzie’s analysis, Volkswagen will surpass Tesla by the mid-2020s to be the leading electric vehicle automaker, selling close to 3 million electric vehicles annually by 2030. Tesla will lag behind by nearly 1.5 million vehicles. Nissan-Renault and Hyundai will also surpass Tesla in annual sales by the end of this decade. General Motor’s absence from Europe will be significant over the next decade and will see the company place fifth on the leader board for global sales.

Barriers to success

A lack of charging infrastructure and high prices have been widely cited as barriers to widespread electric-vehicle adoption. However, we see progress on both fronts.The projected price of battery packs used in EVs continues to decline. We expect the $100/kWh threshold to be breached by 2024, one year earlier than our previous projections.

Cumulative residential and public charging points are projected to grow to 58 million and 6 million outlets, respectively, by 2030. The sector is expected to have a cumulative investment value of $57 billion and $111 billion, respectively, between 2020 and 2030.

Consumers, too, have a close eye on the economics. And while most are in no small part driven by climate concerns, the financial benefits of switching to zero emission, plug-in hybrids, and battery EVs is also a factor. Price parity with ICE vehicles at point of sale has been achieved in the luxury sedan segment and will extend beyond that niche ahead of original projections – a change that will really see EV adoption accelerate.

The future

The rapidly evolving transportation landscape is beckoning new strategies. As traditional automakers enter the EV race, they are expanding their role from being simple car producers by investing in cell and battery manufacturing, mines, and charging infrastructure. Vertical integration will be key to keep costs down and ensure material availability to support growth.

About the author

Prachi Mehta has a diverse background in downstream oil and gas, natural gas liquids, petrochemicals, and electric vehicles. She works as a senior market analyst at Wood Mackenzie, focusing on EVs and midstream markets. She has six years of experience looking at energy markets and working across commodity markets to develop holistic insights.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

The price trend for electric vehicles is clear and not only based on declining battery cost, but additionally based on overall advantages of a simpler manufacturing processes as a direct result of far less moving parts.

So my question is, why should anyone buy a ICE car, if the electric vehicle is: Cheaper to buy, cheaper to charge and cheaper to maintain?

And lasts 3 to 5 times longer than an ICE car?

So who are the 46% of ICE car buyers in 2050? When the economics are changing right now (First announcements of battery packs below 100$/kWh)

According to Wood Mackenzie, the Chinese automakers (SAIC, FAW, Dongfeng, NIO, GAC, GWM, BAIC, XPeng, Chery, BYD and Geely, etc.) all stopped manufacturing BEVs in 2017. That’s nice work, boys. Next time, get one of them high school kids to do the report with the Googly thing.

ICE is 18%, lookt at the graph .

Ridiculous figures 56% ev sales in 2050. Is there something about analysts that blinds them to S curve adouption rates of new technologies. Europe will hit 50% ev sales (bev + phev) sometime in 2023, China in 2224-25 and the US in 2225-26. Who is going to want a new ICE vehicle by the end of even this decade. Sales of ICE vehicles peaked in 2017 and are in terminal decline. Its a double whammy of on the one hand evs are eating their market share, and on the other hand sales are declining because less people want to put large sums into outdated technology that will be worthless in a few years. The next year that vehicle sales get above 2017 recirds the vast majority will be evs. You can argue that traditional auto manufacturers wont be able to ramp up ev manufacture that quick but in reality they wont have a choice as ICE sales will collapse. Either make evs or make nothing

I wonder how Woods McKinsey would have predicted the adoption rate of Flat screen TVs vs Tube… Oh well, they already proved themselves wrong (under estimated) the last 3 years of their “projections”.

But the again.. so did all the other “experts” on EVs, Solar adoption and solar cost, wind adoption and cost, coal retirement, battery adoption, etc.

Grid operators and false “feet dragger” estimators (scaring aren’t investment) really the only thing stemming the tsunami tide.

Surprised that Ford or Toyota not appear in this article! Any ideas?

The oil industry has already seen its point of capitulation, when the Saudis tried to sell outright their oil industry, with no takers. Financial research dictates the end is nigh for oil burning engines of the 20th century. The new technology of battery and fuel cell power beckons and with the current waves of development and demand will be the dominant choice of power trains over the next few years.