From pv magazine 01/2021

On Nov. 18 2020, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s (KSA) Ministry of Energy announced reforms to its electricity sector that appear promising for an acceleration of the uptake of large-scale solar in the country. And as the region’s biggest economy, and the world’s largest producer and exporter of oil, when the KSA moves decisively, the repercussions to the region’s energy sector are significant.

However, when it comes to renewable energy deployment, Saudi Arabia’s plans and announcements have seldom lived up to expectations. And while the Kingdom’s renewable energy deployment target of 58 GW of capacity by 2030 is encouraging, progress toward this goal has been frustratingly slow.

The November 2020 reforms, announced by the Ministry of Energy, are targeted at achieving a number of goals. These are increased generation efficiency and reliability, reduction of liquid fuel use for electricity, and the creation of a “viable and sustainable” electricity sector. Importantly, the package of measures contains a “deleveraging” of the Saudi Electricity Company’s (SEC) balance sheet to the tune of $128 billion, and the provision of a $45 billion equity facility to the SEC for investment in generation and distribution – the latter of which could mean a lot of large-scale solar.

“From what I’ve seen, it boils down to canceling a lot of SEC’s debt, as it was on poor financial footing to say the least. Additionally, it pursues the government’s agenda in terms of reducing the volume of crude that is burnt by the power sector,” says Antoine Vagneur-Jones, from BloombergNEF’s Energy Transitions team.

The retiring of SEC debt sees the company’s debt-to-equity ratio decrease from 2.2 to 0.6, which the KSA Ministry of Energy has described as a “healthy debt level” for a modern utility. Advisers to SEC in the reform process, HSBC and Strategy&, both noted that the measure should allow for further investment in the Kingdom’s electricity sector at appropriate and secure returns.

“Overall, these announcements are expected to create an attractive environment for investment in the electricity sector and contribute to the economic development of Saudi Arabia, in line with the Vision 2030 program,” stated HSBC.

Inside the drivers

As the world’s biggest producer of crude oil, and its cheapest, it should come as no surprise that the KSA’s energy reforms are closely linked to oil prices. Reforms to the country’s electricity sector, and wider economy, have tracked closely with fluctuations in the oil price. In 2020, with oil prices relatively low and peak oil demand looming – by 2035, according to Bloomberg NEF’s New Energy Outlook – there is an increasing imperative for the inefficient burning of oil for electricity production to be reduced, if not eliminated.

“The volume of crude that Saudi Arabia burns in its power sector is monstrously high,” says BloombergNEF’s Vagneur-Jones. “Maybe second only to Iraq – 31% of the crude oil Saudi Arabia produced in 2019 was burnt for electricity. It’s nuts.” The analyst adds that one-fifth of that oil burnt for power generation was heavy fuel oil. “It’s not as polluting as most coal, but still a pretty dire situation for a country that is reliant on oil exports.”

Renewables, including solar, would be well positioned to phase out this oil-fired generation. The KSA currently has around 400 MW of installed solar capacity, built under auctions administered by the the Renewable Energy Project Development Office (Repdo), which was founded in 2017. Low solar power purchase agreements have been achieved, including $0.0234/kWh at the 300 MW Sakaka solar PV project, developed by homegrown renewables developer ACWA Power. At the time ACWA Power CEO Paddy Padmanathan noted that “PV is a no-brainer in our part of the world for a significant source of load.”

As with its Gulf Cooperation Country (GCC) neighbors, demand for electricity in the KSA has been increasing – driven primarily by residential and commercial property air conditioning demand, although additionally through an increase in industrial activity. BloombergNEF expects this demand to continue to increase, although not quite to the 121 GW of peak power demand by 2030 forecast by the government.

Indeed, energy efficiency measures, promoted by the government as a part of its Vision 2030 raft of policies, have been effective in stemming electricity demand growth. In 2019, BloombergNEF notes, electricity demand in the KSA actually fell – “for the first time in many decades,” adds Vagneur-Jones.

On the basis of falling demand in the short term and the existing generation fleet, IHS Markit believes that new thermal generation projects are unlikely to be developed by the Saudi utility, the SEC. Elsa Kiener, a MENA power analyst for IHS Markit, notes that SEC currently has sufficient reserve generation margins. “We think the national utility is more likely to invest in future grid projects than greenfield generation projects,” says Kiener.

Tariff reform

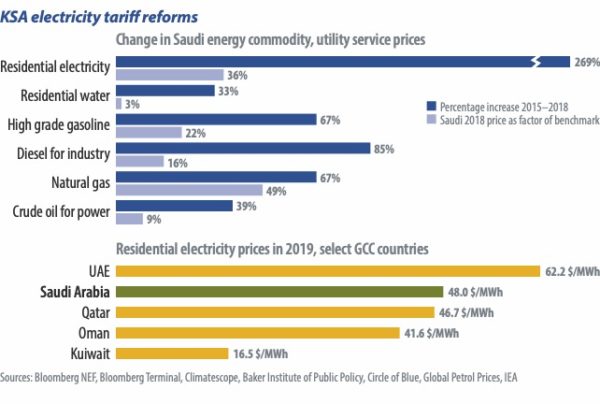

An important driver of the moderation of the KSA’s increased electricity demand has been a reduction of electricity tariffs, which were highly subsidized. In fact, these subsidies were one of the causes of SEC’s parlous state of finances, prior to the November 2020 reforms.

“Electricity and fuel tariffs have been subsidized [in the KSA] and, despite the previous subsidy cut, the electricity retail tariffs are still not cost reflective,” says Kiener. IHS Markit MENA renewables analyst Silvia Macri notes that rooftop PV could also take advantage of higher retail tariffs. “An increasing number of residential and small C&I customers, which account for the large majority of power demand in Saudi Arabia, would be willing to partially reduce their grid electricity consumption with independent solar systems,” she adds. A rooftop PV “net metering framework” has been passed by regulators, but at present prices remain below the point at which distributed solar is competitive.

Promise without certainty

As the world’s eighth-largest utility in terms of total assets, the SEC reforms could very well pave the way for a more rapid acceleration of solar development in the KSA.While oil giant Aramco has so far steered clear of renewable investments, the country could task its Public Investment Fund (PIF), with an estimated $380 billion in capital at its disposal and plans to expand that to more than $1 trillion, to invest in new renewables capacity. The PIF already owns 74% of SEC.

However, the progress of renewables and solar in the Kingdom to date has been unsteady. The 400 MW of solar installed to date is “puny,” and a fraction of the 5 GW of new renewables required annually to meet the government’s 58 GW by 2030 target, according to Vagneur-Jones.

While the SEC reforms have been designed to increase transparency and investment certainty, the shadow of PIF may ward off foreign capital. The Repdo auction process has also been opaque and past renewable announcements have come and gone overnight, including a 200 GW deal with Softbank in 2017.

“A lack of transparency is the biggest challenge,” says Vagneur-Jones. “Renewable targets have been flipped and flopped on over the past few years.”

With an economy heavily reliant on energy exports, the Kingdom will find itself engaging with renewable energy in one way or another. In a column for the Financial Times, Mark Lewis – BNP Paribas Asset Management’s global head of sustainability – notes that the instability in oil prices observed on the back of the Covid-19 pandemic may prove to be minor when compared to the macro trend of energy disruption at the hands of renewables. “From now on, oil will increasingly be competing with the deflationary dynamics of renewable energy,” writes Lewis. He notes that as the lowest-cost oil producer, the Kingdom might actually be the best positioned of all of the major oil producers to ride out the current disruption.

Accordingly, the Kingdom has lofty hydrogen export ambitions. The country’s energy minister, Abdulaziz bin Salman Al Saud – the first Saudi royal to hold the position – has posited that the country will eventually lead the world in hydrogen exports.

If that is to be green hydrogen, produced via renewable-fed electrolysis rather than gas-fed blue hydrogen, then the solar and wind capacity to feed its production will have to be established rapidly. An increasing number of competitor countries are hustling to assume the hydrogen mantle, and many have neither the hydrogen transportation, nor governance and transparency hurdles the KSA faces.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

2 comments

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.