Hydrogen will need nothing short of a groundbreaking invention and a giant windfall of cash to eclipse lithium batteries in the race to become the dominant green transport fuel, according to an expert at the University of Western Australia.

“Right now, hydrogen is not even close,” said Professor Ray Wills, managing director of Future Smart Strategies, told pv magazine Australia.

Markets tend to prefer single-market solutions, Wills said. In other words, monopolies. Think, for example, of Google – despite all the hype around the potential for the democratization of the internet, just a handful of companies are in control. Once a company or technology gains the upper hand, it's difficult to stop its ascent. Market advantage tends to stick.

Which is precisely what Wills believes will happen with lithium batteries, leaving hydrogen in its wake. “Hydrogen as transport fuel is still a long way behind lithium batteries,” he says.

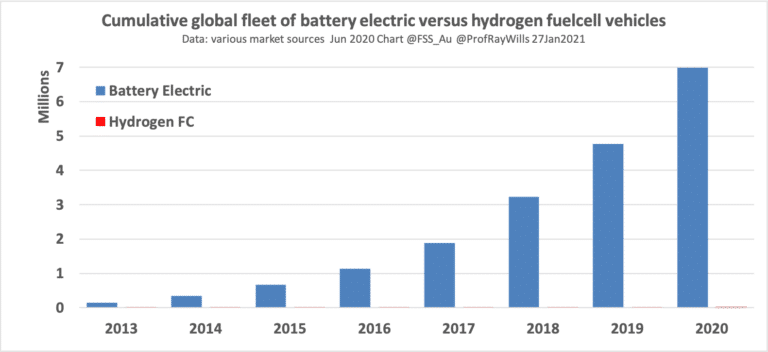

Today, the global electric vehicle fleet is believed to be more than 10 million. According to EV Volumes, an EV sales world database, sales of battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEV) rose from 2.26 million units in 2019 to 3.24 million vehicles in 2020.

These numbers are considerably bigger than hydrogen fuel cell vehicle fleets, which are in the tens of thousands. There are simply more EVs being made at present.

So is it possible for hydrogen to shoot out from behind? Technically yes, Wills says. But it would need a great push – nothing short of a miraculous invention that could double hydrogen’s efficiency would make it real competitor. Does that seem probable? “Not in the next five years,” says Wills.

Hydrogen could take off if lithium batteries don’t perform, or if prices and battery densities fail to meet consumer needs. But given the rapid progress that batteries have made in the last decade, Wills gives little weight to the scenario.

Another problem is the issue of infrastructure. But as Wills notes, electric charging stations are winning the infrastructure battle. “Could be overturned? Yes, if someone were to pour money at it,” he says.

Government funds are still the driving force behind hydrogen infrastructure installations. EV charging station infrastructure, on the other hand, is already being competitively installed. “It just adds a layer to the advantage,” Wills concludes.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

Does the above analysis take account of the following:

1) The need to avoid paying for wind power generators to turn off generation during periods of surplus production. This is leading to the development of green ‘power to x’, namely H2 as a way to absorb power and store it.

2) The need to replace methane in domestic and commercial/industrial space heating is pressing. The development of H2 as a natural gas substitute is well underway, at least in the UK. This is going to create substantial and sustained demand.

3) The aviation industry is actively looking at hydrogen as a fuel and it has little alternative as extensive use of SAF would wreak havoc with world food prices. Airbus are working on it. In surface transport, I’m seeing reports of trucks and trains being tested with H2 fuel cells.

A need to use surplus power from wind (and solar) and a demand from space heating and transport industries will inevitably bring down prohibitively high prices. A tipping point will be reached after which this could happen quickly. Once that occurs, and the infrastructure is in place to produce green hydrogen at scale, it’s attraction (quick filling and plentiful forecourts and good range + familiarity) could see a sudden rush of applications from major car manufacturers.