From pv magazine France.

Solar energy has experienced massive growth in the last decade and the pattern is expected to continue and possibly reach a global generation capacity of 4-5 TW in 2050. Impressive growth in installed capacity naturally raises the question of the future of PV panels after their use, and of their recycling. What is the future of the photovoltaic industry? What problems have been identified and what initiatives are being taken to solve them?

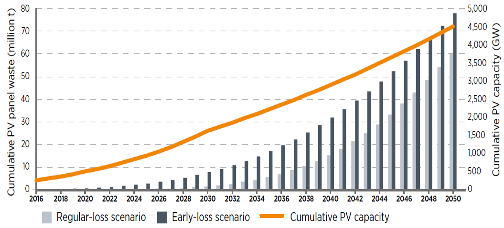

Various models have been proposed and calculations made regarding useful panel life and the replacement of modules before the end of their planned lifecycles. The models indicate the world stock of end-of-life PV modules awaiting processing could reach 1.7-8 million tons in 2030 and 60-78 million tons in 2050. On a European scale, the quantity is estimated at 10 million tons.

The European Union has been a pioneer in module recycling since applying regulations through its directive on waste electrical and electronic equipment, which includes PV panels (Weee directive 2002/19/EC). The legislation requires 85% panel collection and 80% recycling of PV module materials. In France, the collection and processing of used panels has been entrusted by the public authorities to the PV Cycle organization.

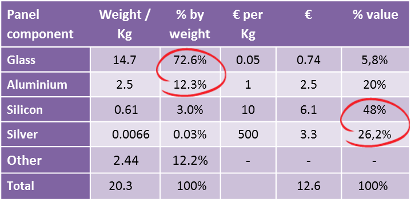

The aluminum frame and front glass represent 80% of the weight of a PV panel. On the other hand, 80% of a panel’s value is bound up in the materials used for the manufacturing of solar cells, in particular silicon, copper and silver. That paves the way for the development of technological solutions offering recovery of the highest-value materials at the highest possible purity.

Disassembling a panel, by removing its aluminum frame and junction box, is easy. The difficulty lies in delamination of the ‘sandwich’ of material which makes up the main body and from which precious materials can be recovered.

The main obstacle to delamination is posed by degradation of the encapsulating polymer, generally ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA).

Methods

The most common recovery methods are mechanical, involve cutting, crushing and sieving and are already deployed on an industrial scale. French water and waste management and energy services business Veolia has invested in its Rousset plant in southern France to treat PV panels in such fashion. The facility was Europe’s first of its kind and can process up to 4,000 tons annually with a 95% recovery rate.

Other companies concentrate solely on recovering specific materials from dead panels, such as glass. Those ‘downcycling’ approaches may meet the requirements of the Weee directive but ensure only low-purity materials are recovered.

However, the European Commission has backed research and development projects aimed at higher-value recovery efforts.

The approach developed by Italian company Sasil, under the framework of the commission’s low-carbon Life program, or that undertaken by German engineer Geltz Umwelt-Technologie are two such examples.

Carbon footprint

The French National Institute of Solar Energy (Ines) is developing a new mechanical cutting approach. Early results have been encouraging and show it would be possible to recover high-purity glass, plastics and metals. With an industrial scale set-up planned, the Ines approach would produce materials which could be reused in a circular economy, improving the carbon footprint of solar panels. Other innovative developments are exploring the use of fluids and supercritical or ionic liquids to recover precious metals.

Industrial recycling of PV panels at the end of their useful life should rapidly unfold in the coming years. The research being carried out in the field also informs the ecological design of the products of tomorrow, focusing on recyclability and environmental footprint, a field of innovation still under-explored by industry players.

Sustainability in solar and storage

This article was supplied by France’s National Institute for Solar Energy (Ines), an R&D center for advanced photovoltaic solar technologies and their integration into electrical systems and intelligent energy management.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

1 comment

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.