From pv magazine Australia.

Research by University of New South Wales (UNSW) psychologists linking perceptions of the risk posed by climate change to willingness to reduce personal carbon emissions gives pause for thought on the role of leadership, the potential of the bushfire crisis to change attitudes and the difference individuals can make.

Commenting on Friday in an article on the UNSW website, Belinda Xie, a doctoral candidate in the university’s School of Psychology – and one of the authors of the study Predicting climate change risk perception and willingness to act – said: “It is important to acknowledge that we are all climate deniers to some extent, and then understand how and why we reached this point.”

Xie and her fellow researchers have extended previous work by Sander van der Linden at the University of Cambridge, which established the Climate Change Risk Perception Model in 2015 and tested a representative sample of the U.K. population to find a variance of 68% in their perception of the risk posed by climate change.

Beliefs vary

Those findings indicated the U.K. respondents entertained a wide spectrum of belief in the validity and urgency of the climate change threat.

Van der Linden’s research was designed to collate known influences of people’s perceptions of climate change. His model identified four key factors: socio-demographic, cognitive, experiential and socio-cultural, which underpin climate change risk perception. The UNSW team have added two more: prioritization of free market ideology and “beliefs about the efficacy of climate change mitigation action”.

Xie told pv magazine her impetus for expanding on van der Linden’s model and applying it locally was that “In Australia we are vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, as we’ve just seen with the bushfires, and at the same time our political situation is such that we constantly fail to do anything about it.”

The road to responsibility

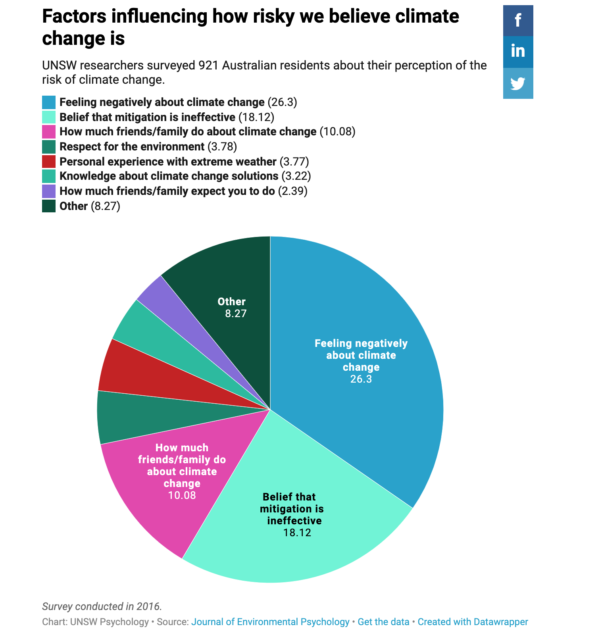

Xie’s group designed a survey based on van der Linden’s and including questions about their additional factors, and collected responses from 921 Australians said to be representative of the general population in terms of age and gender.

“We looked at demographic factors, people’s knowledge about climate change, broad societal values and also social factors such as what your friends and family think,” Xie said, to determine not only risk perception but “behavioural willingness” to act.

The survey was completed in 2016 and the results, published last year, identified the three most significant factors influencing perception of climate change risk as:

- Feeling negatively about climate change – “The worse or the more anxious it makes you feel, the more likely you are to want to do something about it, which makes sense,” said Xie.

- Belief mitigation is ineffective – “This was interesting because we hear a lot from Australian media and the government that mitigation should not be implemented, that it can’t be implemented, so it’s unsurprising that a lot of Australians have these views and that these have a big impact on their subsequent willingness to act.”

- How much friends and family do about climate change – This has to do with the social norms which influence people, according to Xie. “If your friends, family and other people who you think are important are taking action, then you’re more likely to,” she said.

The catastrophic bushfires Australia has suffered since spring offered “a rare opportunity” for people to feel united in pushing back against climate change and ineffectual policy, according to Xie. The fact city dwellers in eastern states were affected by poor air quality due to smoke haze should have given many more people than were directly affected by the fires the sense their way of life is under threat.

“We know from our research that personal experience with extreme weather events does increase people’s concern about climate change and how much they want to act on it,” said the doctoral candidate. “But it’s key that people make the connection between that extreme weather event and climate change.”

Obfuscation and the media

Xie referred to misinformation – such as blaming arsonists for the fires or the assertion by politicians Australia has always been prone to bad bushfire seasons – as confounding and confusing factors affecting people’s willingness to act.

That exposes an even greater failure by Australia’s government than lack of policy development: the failure to articulate truthful and consequential information to the electorate.

In an environment of federal government obfuscation, a fractured news cycle could also derail the sense of urgency accorded climate change. Xie cited the heavy rains falling on parts of Australia’s east coast and extinguishing fires including the destructive Currowan blaze – as well as the threat posed by the coronavirus – as psychologically distracting to the individual and community resolve to fight climate change.

“Acting on climate change is a bit like cutting back on junk food,” said Xie. “We all know it’s right to act but we seem to be very good at making excuses not to do it.”

The power of the collective

The UNSW researcher said campaigns such as the Roadmap to Zero initiated by independent MP for the federal seat of Warringah, Zali Steggall, tap into the motivation groups of partially like-minded people can exert on one another to reinforce their resolve and ability to make a difference.

“Humans are social beings and a lot of what we do or think is motivated by other people, so turning this into a collective, group action I’m sure will encourage more action and more long-term action than if any of those individuals were to try to make these changes by themselves,” Xie told pv magazine.

Prime minister Scott Morrison and his Liberal party are expected to further promote technology and market forces as the best means of responding to the threat posed by climate change. Energy and emissions reduction minister Angus Taylor was quoted by The Weekend Australian newspaper on Saturday as saying: “Technology now needs to be a centerpiece of the international approach to climate-change action … The lesson from the United States is that technology and capitalism offer the way forward in making the energy transition.”

Free market ideology

Xie and her colleagues included in their survey six items to “measure the relative priority placed on a system that supports an unrestrained free-market compared to a system that sustains environmental quality”.

Their study found greater prioritization of an unrestrained free market “was associated with less willingness to take personal action or support societal interventions to combat climate change”.

As political discourse, Morrison’s proposed solutions to climate change contribute to the sense personal action against the threat has no efficacy, which in turn reinforces people’s feeling it’s challenging to live without having an impact on the environment.

“Australia is a wealthy nation with high emissions so it’s difficult to live here without being some sort of hypocrite and engaging in action that involves emissions,” Xie wrote on the UNSW website. However, she added, it’s important to recognize this and take action to move beyond our own climate denialism and urge others to do the same.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

There are three independent arguments for a rapid energy transition:

1. It’s cheaper.

2. It would halt climate change.

3. It would practically eliminate health damage from outdoor air pollution.

Consistent denialists have to disbelieve all three propositions. The cited study ignored the third. This is odd, because the scientific basis is not only rock-solid, it is simple and intuitive. Breathe in soot, get sick. (If you aren’t impressed by my MD and white coat, here are the dead lab rats, here are the slides of autopsied lungs, here are the tissue cultures, here is the appealing child bravely facing severe asthma.) The house of cards of pseudoscientific climate denial cannot be built for health. And it’s enough by itself to justify the energy transition.

It is important to note here that energy is Just one art of the climate change puzzle, there are lot of other parts which contribute to climate change exponentially, like food/cattle/transport (using SUV’s & 4 wheel drives in the city to haul kids to school every day (and talk about climate change)/ we need sustainable action every day in every activity from taking a 4 minute shower to sing recyclable bags/ energy conservation/heat insulation/light sensors/ consuming meat/not using plastics/ all lead to sustainable living.