From pv magazine energy+storage

Germany and California are global leaders in driving the energy transition, with governing bodies from both sides working together on energy issues. Can you tell us the background and history of this collaboration?

California and Germany have been working together successfully for many years. We are pleased that the Germany-California Bilateral Energy Conference, which we are hosting together with the California Energy Commission for the third time, has further intensified the exchange with California. After Sacramento and San Francisco, the conference will take place in San Diego this year. The political exchange about the necessary next steps and the exchanges with business about new technologies is vital for both partners.

What are the immediate goals and objectives of the Germany-California Bilateral Energy Conference? How do you see this progressing in the future?

For decades, California has played a pioneering role in climate and energy policy. Many other U.S. states and countries have adopted Californian regulations, not least because California is a good example that environmental protection and economic development are not mutually exclusive. Therefore, an exchange of best practices with the people that drive the energy transition in California is most helpful. We will, for example, discuss the most efficient flexibility options for the power sector and the role of storage, ways to accelerate the transition in the transport sector, and how to better incentivize efficiency.

What are the policies and regulations that will be most effective in pushing Germany toward decarbonization?

There are various measures, of course. The establishment and support of renewables has been done through the feed-in-tariffs to bring in onshore and offshore wind power, biomass and PV. And for the last two years, this has been spurred by auctions, which has worked well to ensure that we receive the lowest possible costs. Ten years ago, costs for PV were €0.15 to €0.18 per kWh. And now, for rooftop we are around €0.10, and our large-scale projects are €0.50 to €0.60 per kWh. Policy drives the amount of capacity that we are looking to install each year.

Grid expansion is another key measure to the energy transition. Wind onshore, is installed mostly in the north and east of Germany, and with offshore at sea, but the highest demand for energy is in the south and west of Germany. This is of course a big undertaking to cross the whole country.

But it’s even more than that. It is also heating, CHP – which we have to approve. In all different parts of the energy system, we have to give frameworks for regulation, and to step out of old technologies. We will step away from all nuclear by 2022 completely. And now, we are designing a regulation to phase out of coal. Germany has a large share of coal in our energy mix.

Yes, Germany recently announced bold plans to phase out coal by 2038, which will revolutionize its energy infrastructure. What are the next steps forward on this journey and what are the implications and challenges you face?

We are looking at an auction system to motivate people to shut down their hard-coal fired power plants. With regard to lignite-based power plants, we are currently negotiating the terms for the shutdown of the plants. The negotiations are quite complicated because the lignite-based power plants are very important to the economies in the regions in which they are situated. The discussion is not only about energy, but also about creating viable social and economic structures for the workers, people, regions and local governments that are affected.

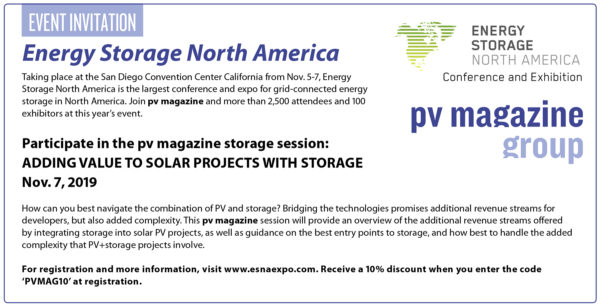

Join California and Germany at Energy Storage North America

The Germany-California Bilateral Energy Conference will take place on November 5, 2019 in San Diego, California. It is free to attend and will be collocated with this year's Energy Storage North America conference and exhibition.

The Germany-California Bilateral Energy Conference will take place on November 5, 2019 in San Diego, California. It is free to attend and will be collocated with this year's Energy Storage North America conference and exhibition.

To attend ESNA and receive a 10% discount, enter the code ‘PVMAG10' when you register. Be sure to join us for our pv magazine ‘Adding Value to Solar Projects with Storage' session of the conference on Thursday, November 7, 2019 at 10:45 a.m.

Germany has an aggressive goal to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions by at least 55% from 1990 levels by 2030. Where does the country currently stand?

Well, we have to differentiate between the sectors. In the energy sector, we will achieve our 2020 goals. If everything takes place that we have laid out – such as phasing out coal, establishing more renewables, bringing more gas into the system, such as CHP – then we will achieve our goals by 2030 in the energy sector.

In the heating sector, we are not there yet and will not achieve our 2020 goals. And if we don’t establish additional measures, we also will not achieve our 2030 goals. The same goes for the mobility sector. We will achieve it in the industrial sector, but not in mobility, and not in heating.

This is why Chancellor Merkel has established the Climate Cabinet – to identify additional measures to achieve the ambitious greenhouse-gas reduction goals over the next decade. CO2 pricing could be one of the essential, and crucial, instruments to achieve our greenhouse-gas reduction goals.

With a world class automotive industry, the transport sector is responsible for approximately 20% of Germany’s CO2 emissions. What are the biggest challenges for the country in addressing emission reductions for this sector?

The primary challenge is that it has a lot to do with behavior. The energy industry is quite easy by comparison, as we can develop renewables through market design and we are working with small numbers of utilities and industry companies. The mobility sector is like energy efficiency in that you have to address people’s day-by-day behavior, which is a great challenge.

Secondly, the automotive industry is very important to the German economy. To switch the industry to other technologies is quite ambitious and complicated. We want to encourage more EVs on the streets, but it is not so easy for manufacturers. Vehicles running on battery technology aren’t cheap, and don’t provide long-distance range – so again, the people have to accept it, and drive demand.

Of course, the mobility systems in cities and rural areas are very different in their challenges.

Approximately 40% of all electricity consumed in Germany comes from renewables, and this share will increase to at least 65% by 2030. Is the government on track to achieve this goal? What is the projected energy mix moving forward?

We are on track, but it doesn’t come easy. The energy mix is something that is being highly debated, and also contested, among parliament and different interest groups now. What we need is a mix of PV, onshore and offshore wind – but there is a lack of acceptance when it comes to onshore wind. It was very popular five to 10 years ago, but as the costs have come down and deployment has grown, so has reluctance. People don’t want to look at windmills. There is also large debate among environmental groups. Climate activists support windmills, but conservationists and bird protection groups are in opposition.

It is complicated, and this is where politics come into play. Similar to grid expansion, we must find where support lies and then make compromises to deliver policy for onshore wind. This is what is being debated this year, and hopefully by autumn, we will have an end result.

What role will storage play in Germany’s energy mix and the energy transition?

For storage we have to differentiate between technologies for electricity and gas in the first place, and the use cases for which the storage technology is needed. For durations of seconds or minutes for frequency stability, for example, batteries are one option on the market for balancing energy run by the grid operators. When it comes to storage for the duration of a day, a week, or even longer – we believe these options will be incentivized by the wholesale electricity market, and not regulation or grid tariffs.

In the north of Germany, we already have renewable penetration of about 80%, and with this amount of renewables, you need all available flexibility options. The cheapest way of integrating renewables into the system in the long run is expanding the grid. We will use other flexibility options like digitization, flexibility in demand and supply, storage, and cross border trade according to their costs, starting with the cheapest option. We are always focused on cost efficiency and technical skills and in the mean- time, investing in innovation for better storage technologies over the next decade. I believe in the second half of the 2020s, from 2026 onwards, we will see more and more storage come online in the system.

How is Germany currently supporting clean technology innovation and industry to spur the necessary growth of renewables in the portfolio?

We have an R&D budget of approximately €1.3 billion for innovation in energy. This is being used for PV, and integrating PV with storage, hydrogen electrolyzers, and so on. We support large demonstration projects, so-called “living labs,” for the energy transition. Actually, the Federal Minister for Economic Affairs and Energy, Peter Altmaier, just awarded project proposals from different consortia to bring forward innovation in decarbonization across mobility, heating and in transport systems through various measures. For example, integrating more renewables into the system, adding various storage, and especially by producing hydrogen and bringing hydrogen into the steel industry and transportation systems.

We are looking to scale up these energy technologies so that they are there when we need them, and we will need them by about 2030. We are now investing a lot of money in order for the private sector and science sectors to work together so that these technologies become competitive and cost efficient in the next 10 years.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

Not very hard-hitting questions.

One way to contain opposition to grid expansion plans is to go for good design of pylons and other high-voltage infrastructure. France, Denmark, Finland, Italy, the Netherlands, even the UK are making progress on this, while Germany lags. Doubling the cost per pylon is worth it if the alternatives are burial or abandoning the project.

Feicht apparently does not understand the pace of change in electric cars and trucks, repeating the canard of high costs. This is no longer true on a TCO basis (even at outrageous German household electricity rates), and battery costs show a high learning rate. Range is a solved problem – not only Teslas have over 300km, more than it is safe to drive without a stop. There is already no economic or operational case for buying diesel buses, even ignoring the massive health costs. In a few years’ time, the political problem will be unemployed workers from shuttered ICE powertrain plants and their useless supply chains.