From pv magazine, September 2019

Frank Asbeck turned 60 years old on August 11, and many will remember him for his company SolarWorld AG, which once led German PV cell and module manufacturing before its bankruptcy in March 2018. But Asbeck also did pioneering work on another front: his efforts were critical in getting the European Union to adopt a Minimum Import Price (MIP) to protect European PV manufacturers from overseas competition, mainly from China.

Asbeck and SolarWorld were also instrumental in getting the Obama Administration to levy anti-dumping (AD) and countervailing (CVD) duties on Chinese manufacturers in 2012, the first round of trade measures adopted to protect U.S. manufacturers (like SolarWorld’s former operation in Oregon) from cheaper modules made in China.

In both cases the aim was to protect domestic industry from what was alleged to be unfair competition from Chinese manufacturers, which were (so the claim goes) either selling below their actual costs (antidumping) or benefiting from unfair subsidies their government was providing (the gist of countervailing duties or CVD).

These cases took a rather narrow view of “domestic industry”, being concerned mainly with upstream PV manufacturers and not the solar PV industry at large. On the downstream side, most consumers, installers, developers and EPCs were against putting up walls to shield domestic manufacturers. Protectionist policies, whether in the form of MIPs, AD or CVD, increase prices, making PV projects more expensive, and in some cases prohibitively so.

Since Asbeck and SolarWorld championed tariffs as the way to protect European and U.S. manufacturers, much has happened in the solar industry and for that matter, trade relations in general. The principles of free trade and globalization have come under attack from many sides, with the Trump Administration being the most vocal. In fact, the embodiment of free trade and globalization, the World Trade Organization (WTO), has been lambasted by Trump, who is blocking appointments to the WTO’s Appellate Body, saying its judges have overstepped their mandate.

For the solar PV industry, which became mainstream as a globalized industry around the turn of the century, the specter of increased trade tariffs in a wide range of countries risks undermining the great strides solar has made in reducing its LCOE. On the other hand, having an extended solar value chain in place has its benefits: if a country lacks a significant manufacturing base and relies to a great extent on imports to feed its solar installations, it will suffer in terms of energy independence, especially as PV and battery storage continue to displace conventional energy generation.

Each market also has its own characteristics (environment, roof structures, etc.) and the more extensive the solar value chain, the better the country can fashion its solutions to such characteristics. Finally, there is the employment argument, which equates a more extensive solar value chain with a more diverse and technologically advanced workforce in the strategically important field of renewable energy. The employment argument can also go the other way along the following lines: the lower the cost of solar, the more projects are planned and built, which in turn stimulates employment on the downstream side.

The United States probably offers the most complex picture, since the old AD and CVD duties remain in place and have been sandwiched together with myriad other tariffs established during the Trump presidency. These Trump tariffs include Section 201, 232 and 301 duties, the final of which is part of the Trump administration’s broader campaign to pressure China to change the way it handles foreign trade and investment.

Even before Donald Trump was elected, China had responded by introducing its own tariffs, with one of the victims being U.S. polysilicon producers. This was one of the last areas where the U.S. still has a significant production footprint in the PV industry. Unlike Section 301 duties, which apply only to China and cover cells, modules and inverters (at a duty rate of 25%, up from 10% starting May 10), Section 201 and 232 duties cover all countries exporting to the United States.

Chile’s open borders

In India a 25% safeguard duty has not stemmed the influx of foreign modules. According to analysts at Bridge to India, one year after the tariff was imposed in July 2018, the share of foreign modules continues to hover around 90%, showing how difficult it is for governments to steer markets with tariffs.

In the European Union, the abolition of the MIP created a virtual solar renaissance, with solar installations in the EU forecast to grow by as much as 80% year-on-year in 2019, after the MIP was rescinded last September.

In both India and the EU, the lack of manufacturing depth, not only on the PV side but also with batteries, remains a central issue. And with Trump erecting barriers across the Atlantic we could see governments in the Old World consider putting up their own walls to protect and grow their technology and manufacturing base.

The concern is that such measures and countermeasures could spiral out of control and turn a truly globalized market into many walled gardens with artificially high prices. This is clearly not a scenario in line with fostering clean energy and combating climate change. On the other hand, a mega-deal between the United States and China could bring us back to the path of globalization and free trade and with it the hope of addressing climate change on a truly global level.

Eckhart K. Gouras

Unintended consequences in Brazil

Trump’s (clean energy) trade war

U.S: President Trump and Chinese leader Xi Jinping meet at the G20 summit in Osaka in June 2019.

The United States has developed a pugnacious trade policy under President Trump, and the solar and energy storage industries have found themselves caught in the middle of new trade wars. But while many have argued that the imposition of the Section 201 tariffs was an attempt by the Trump Administration to destroy the nation’s solar market, there is as much or even more evidence to suggest that this really is about protectionism and the use of trade as a weapon in international relations.

To make sense of this, it is important to recognize that President Trump is not the only player here. Most of the important actions that the Trump Administration has engaged in have come from the desk of U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, a veteran of the Reagan Administration and a proponent of an aggressive, protectionist trade policy.

Tariffs, tariffs, tariffs

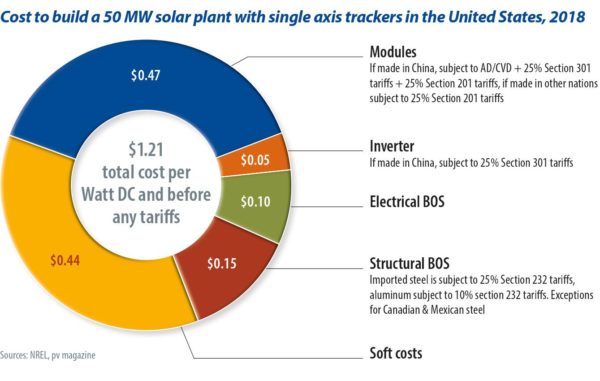

There have been multiple sets of trade duties initiated by Lighthizer’s office, often under dictates from Trump himself. The Section 201 global trade duties on solar cells and modules had the most obvious impact on the U.S. solar market, but there are also the Section 232 global tariffs on imports of steel and aluminum and several rounds of Section 301 duties on a wide range of products that include PV cells and modules, PV module components and inverters from China.

Taken together, there is essentially no part of the U.S. solar and energy storage markets that is not affected by one or more of these tariffs to some degree. As shown in the chart to the upper right, together the components affected by one or more tariffs make up more than half of the cost of a utility-scale PV system.

However, the Trump Administration has also provided two big exceptions to Section 201 – one for modules using SunPower’s Interdigitated Back Contact (IBC) PV cells, and a more recent one for bifacial solar panels.

And this is not over yet; Trump is planning to impose tariffs on a range of products being imported from China at a rate of 10% as of September 1, including lithium-ion batteries.

Market effects

None of this has been good for the U.S. solar market; however the actual effects are more complicated than one may guess. Even with the Section 201 tariffs most PV systems still pencil, and solar projects are still being built to comply with renewable energy mandates, to meet corporate clean energy goals, as well as simply because they make sense economically.

What Section 201 did more than anything was to interrupt the market for a good six months or so while the U.S. solar industry knew that a change was coming but did not know what level of tariffs would be set.

And even when taken together, the various tariffs imposed by this administration did not fundamentally change the attractive economics of PV systems in most areas. However, they did have more serious effects on specific companies and even whole industry segments.

Encouraging manufacturing?

Aside from the Section 301 tariffs, which appear to have been imposed primarily as a punishment/aggressive bargaining tactic by the Trump Administration, the rhetoric behind most of these tariffs, including the Section 201 duties, is that they will protect and enable U.S. manufacturing industries.

The Section 201 tariffs were definitely a key factor in the four large U.S. solar factories totaling 3.8 GW of annual production that have either come online or are currently under construction. However, every manufacturer who pv magazine spoke with also identified Republican tax reform, which cut corporate tax rates, as another main factor.

Also, by raising the costs of raw materials, these tariffs are negatively affecting the very industries they are supposed to be supporting. A prime example is the racking, tracking and mounting systems makers, who were affected by higher steel prices due to the Section 232 tariffs, and U.S. PV makers have also said that their supply of aluminum frames and other materials is being affected by Section 301 tariffs on their Chinese suppliers.

Additionally, some companies, including First Solar, are now arguing that the exemptions to Section 201 – more the bifacial exemption than the exemption for SunPower’s IBC – undermine the effectiveness of the tariffs as a tool to incentivize manufacturing.

So like other aspects of the Trump Administration’s trade policy, the rapid and unpredictable changes created by these exemptions makes long-term business planning difficult and throws supply chains into chaos.

In the end, nothing is certain except that under the current administration the trade war isn’t going away any time soon.

Christian Roselund

Shifting destinations

The impact of United States’ removal of preferential treatment for Indian PV cell imports, whether assembled into modules or not, will be fully reflected in Q2 2019 figures, however, it is clear that India’s PV manufacturers are already looking at alternative markets – and having some success.

The United States continued to be India’s largest export market at INR 16,500 lakh (US$23 million) in Q1 this year – the situation may change as figures for following months become available, with the impact of 25% tariffs coming into effect – but there is a huge jump in exports to some markets.

While the figures for Denmark, India’s second largest PV export market in 2018-19, are not available for the quarter, Belgium emerged as the second largest market at INR 3000 lakh (US$4 million) – more than for the full year 2018 total of INR 2400 lakh (US$3 million). Exports to South Africa stood third at INR 1100 lakh (US$1.5 million).

Open doors Down Under

Topping the countries which registered significant growth in Q1 is Somalia, where India’s exports reached INR 900 lakh (US$1 million) against year 2018-19’s total of INR 2 lakh (US$2,800).

Market trends show the European Union (Belgium, Portugal, Sweden) and African countries (South Africa, Somalia and Ghana) – in addition to Asian countries like Korea and Pakistan – are emerging as significant markets for Indian modules.

These reported figures tend to be in line with the views of Vikram Solar’s Chief Financial Officer Rajendra Kumar Parakh, who said that with the United States becoming a costly proposition, Indian solar manufacturers that have already lost the domestic market to cheaper Chinese imports, “will now target Africa, The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, and other rapidly growing solar markets to export.”

However, given that Indian solar manufacturers are finding it challenging to match aggressive pricing of Chinese solar equipment within the global markets as well, the demands are rising for the Government of India to provide incentives on export to help them go toe-to-toe with the global suppliers.

Why exports?

In July 2018, India applied a two-year safeguarding duty on solar PV cells and modules from China and Malaysia, in order to protect domestic players from the steep rise in cheaper imports. In line with the notification issued by the ministry, a 25% safeguard duty was imposed between July 30, 2018 and July 29, 2019. The duty tapers down to 20% between July 30, 2019 and January 29, 2020, and to 15% from January 30 to July 29, 2020.

The duty, however, didn’t deliver the intended results: Solar developers have chosen to shift source of import rather than sourcing higher-priced products from domestic manufacturers. So, there has been a surge in cheaper imports being rerouted though locations such as Vietnam, Singapore and Thailand, where the duty is not applicable.

In fact, a recent Bridge to India report says that the share of imported solar modules used in Indian solar projects is still around 90% – the same as before imposition of safeguard duties.

With a foothold lost in the domestic market to cheaper solar imports, Indian solar manufacturers are eyeing the untapped and emerging solar markets globally to generate revenue.

Uma Gupta

One year without tariffs – alive and kicking still

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

1 comment

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.