In a 20 page special report titled South Sudan’s Renewable Energy Potential, USIP argues that a “green pivot” towards renewables and, in particular solar PV, could help put the world’s newest country, which has been in the grips of a long and brutal civil war, on a path to sustainability.

The report’s authors say solar PV has the potential for the most immediate improvement in the Republic of South Sudan – the world’s least electrified country – due to its relative longevity, attractive prices, off-grid possibilities, scalability, ease of installation; and the country’s high solar irradiation levels.

Decoupling

Solar also has the potential to help decouple South Sudan’s economic growth from the geopolitics of oil and gas.

Before January 2012, the main economic driver in Sudan was oil; however around 70% came from oil wells inside South Sudan.

After South Sudan achieved independence in 2011, conflict arose between the two countries, prompting the South Sudanese Government to shut down its entire oil production.

Initially lauded, the decision quickly had a detrimental impact on both the economy and electrification. And while an agreement was eventually reached in this matter, conflict again manifested itself, this time taking on an ethnic dimension.

Civil war erupted in December 2013, with South Sudan left reeling from famine, tens of thousands of deaths and over 30% population displacement.

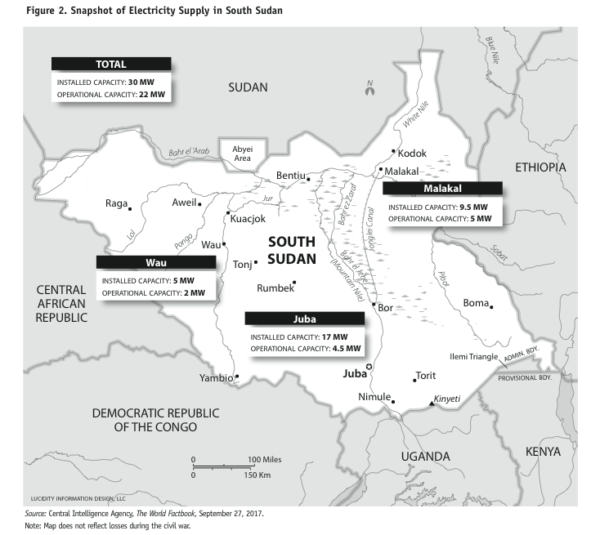

Currently the country’s main energy source is self-generated diesel. Before 2013, the country had installed a paltry 22 MW of operational electricity capacity, all of which came from diesel and heavy fuel generators, and most of which were located in just a few cities.

Shining a light

There are three immediate opportunities where solar could yield both short- and long-term benefits for South Sudan, says USIP:

- Individual nongovernmental organization compounds;

- Health facilities, such as hospitals and clinics; and

- The humanitarian operations servicing internally displaced persons camps outside the destroyed regional capitals of Bentiu and Malakal.

Regarding the third opportunity, the report author’s write, “… internationally funded humanitarian programming can launch an expansion in solar power generation, offering short-term energy benefits and cost savings while building an enduring infrastructure that will outlive the conflict and contribute to peace and stability over time.”

Funding the transition

USIP says South Sudan’s energy transformation needs to be donor-led for two key reasons: (i) donors provide the funding to sustain current humanitarian operations, including existing diesel energy budgets; and (ii) if solar energy infrastructure is to transition to local ownership or to benefit local communities in the mid- to long term, it needs to be managed and maintained by actors likely to remain in South Sudan over a similar period.

The report also notes that the gap between the need for international organizations and NGOs to reduce costs and funding pledges is widening, and that transitioning to a renewable energy system will help to ease this.

“The transition would pay for itself and begin to generate cost savings within two to five years,” state the authors. “It would create desperately needed energy infrastructure while supporting ongoing humanitarian operations.

“These long-lasting, clean energy assets could support future reconstruction and health, education, and social service delivery and would carry the additional benefit of being in place and, likely, of having been paid for. The pivot would also create new entry points for conflict resolution and peace building.

“For example, the transition from a solar system that serves a humanitarian program to one that supplies a local institution (such as a local utility or hospital) would generate opportunities for cooperation between communities driven apart by the civil war to determine issues such as the placement, oversight, management, and maintenance of the solar system.

“Such a shift would create physical assets for peace that could support both physical reconstruction efforts and provide new hooks for conflict resolution.”

Challenges

While there is much potential for solar in South Sudan, there are a number of challenges to overcome, including looting and destruction of property – where solar panels have been targeted in the past – and limited trained personnel.

These challenges, however, also provide opportunities. For example, job creation and the involvement of local communities.

And of course, solar also allows South Sudan the possibility of setting a path different from one reliant on oil and gas.

To achieve its solar vision, USIP recommends, among other issues, beginning donor-level discussions and implementing pilot solar PV projects.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

1 comment

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.